Why should investors care about biodiversity? Part 3

There are multiple reasons why mainstream investors and companies should be paying more attention to biodiversity loss. One reason (among many) is it actually makes good business sense.

Summary: Biodiversity loss has, quite rightly, been in the news a lot more over the last few years. After having been the poor cousin of carbon and pollution, it's now getting some of the focus it deserves. It's important to remember that while climate change and biodiversity loss are linked, the solutions are often different. This blog takes the financial argument a bit further, and talk about practical solutions that food companies can apply at scale. Solutions that can form part of their strategic and tactical response to the changes that the transitions will bring.

Why this is important: Actions need to make financial sense as well as positively contributing to reducing biodiversity loss.

The big theme: There are real concerns about our ability to feed the world, while at the same time trying to reduce the impacts on our natural world. The resources are not limitless. Pretty much all of our economic system is actually dependent on nature - it's hard to think of many societies that would survive the collapse of their natural environment. This rather quickly shifts into the universal investor way of thinking. Put simply, we are dependent on the wider economy and society for the majority of our long term financial returns, so it makes financial sense to invest at least part of our portfolio in ensuring that it continues to be healthy and sustainable.

The details

There are multiple reasons why mainstream investors and companies should be paying more attention to biodiversity loss. One reason (among many) is it actually makes good business sense. Earlier this week we wrote about one part of this - specifically milk. For today’s blog we explore a bit more the financial case for caring about biodiversity and for making the changes that will help our biosphere recover. Some of the points we make might be familiar, some might not. My favourite is about pasta made from peas.

We are focusing on solutions (and there are many - some easy and some hard) - because from our perspective finance is supposed to be about finding solutions to society's wants and needs.

It's important to be clear up front, while there is much that we can do, change will bring with it costs and disruption. Plus, as with the energy transition, we need to understand that we are in the midst of a complex balancing act - ensuring that we can continue to feed the world, at prices that the average family can afford, while also looking to protect our longer term futures. This means change will take time, especially as peoples livelihoods are involved.

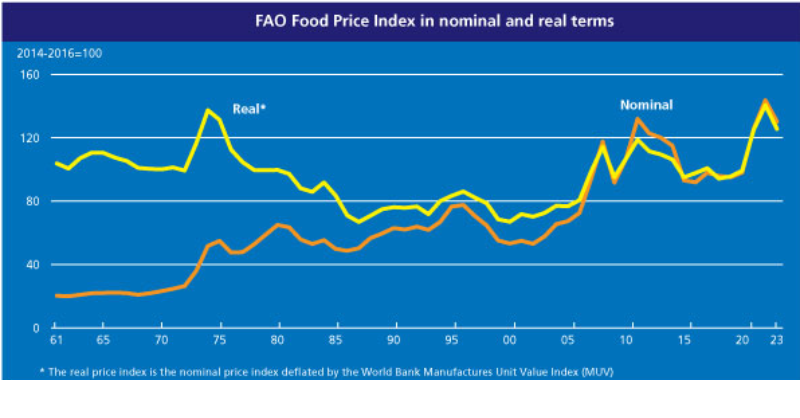

For today we look at food. Food prices globally have been rising strongly since mid 2020, and while they are down on recent highs (seen in early 2022) they are still some 30% higher than at this time in 2020. It's not clear yet if this is a mid term blip, as we saw in the period from 2010 to 2014, or if it's the beginning of a period of sustained higher prices (as was argued in a recent blog). What is clear though is that we are now well into an extended period of quite massive food price volatility.

We are not arguing that these price rises are only due to biodiversity loss. The point is more that recent price volatility may end up being the catalyst that pushes investors to think differently about food supply, food cost/prices and food security. And the loss of biodiversity is going to be a big factor in all three. As with most transitions, this is both a risk and an opportunity.

So before digging down into this, let's do a quick recap of the main reasons why we think investors and companies should be doing more to reduce biodiversity loss.

One obvious answer is because it's the right thing to do. We are all dependent on our natural systems for our economic, social and mental welfare, and so we should care about sustaining them. Financial analysts talk about the extent to which companies are highly or very highly dependent on nature. An example is the 2021 report from the Banque de France, which said that:

“we find that 42% of the value of securities held by French financial institutions comes from issuers that are highly or very highly dependent on one or more ecosystem services”.

But if we think more broadly, pretty much all of our economic system is actually dependent on nature - it's hard to think of many societies that would survive the collapse of their natural environment. This rather quickly shifts into the universal investor way of thinking. Put simply, we are dependent on the wider economy and society for the majority of our long term financial returns, so it makes financial sense to invest at least part of our portfolio in ensuring that it continues to be healthy and sustainable.

The second answer is that we will likely be legally obliged to do so, and fairly quickly. This was the topic of a blog we wrote recently that looked at how the “biodiversity as a legal responsibility” debate might develop. 👇🏾

And then we have the financial argument. For those who believe that their prime (not only - just prime) responsibility as investors is to generate a fair financial return on the capital invested - this might be the most compelling argument. We touched on this in an earlier blog we wrote on a report published by the Rotterdam School of Management, where they discussed investing for agricultural impact. 👇🏾

Today, I want to take the financial argument a bit further, and talk about practical solutions that food companies can apply at scale. Solutions that can form part of their strategic and tactical response to the changes that the transitions will bring. Put simply, actions that make financial sense as well as positively contributing to reducing biodiversity loss.

By understanding the choices that food companies face, we (investors, employees, advisers, and stakeholders), can work with them to generate the environment where change becomes the easier option.

I am going to assume that you know about the risk that the loss of biodiversity brings to our economy and society. And that your main interest is in what we as investors and companies can do to make a difference. If you want to read more can I suggest the content on the Royal Society website, which you can find here or if you want a longer read, the recent Dasgupta Review (summary and video here)

Agriculture as a key driver of biodiversity loss

According to the UN, agricultural expansion is said to account for 70% of the projected loss of terrestrial biodiversity. Agriculture directly impacts biodiversity loss through land use (loss of habitat), land degradation, and through the damage done by many farming practices including fertiliser and pesticide use, and water extraction.

What can companies do in practice that makes a real difference, both in terms of sustainability and financially?

There is no simple and easy single solution to this. There are a range of actions that can be taken, some easy and some harder, that together can make a positive difference. So we should think of this challenge as having a suite of solutions, it's not an either or choice , its and … in the words of the now famous film, everything, everywhere, all at once.

One obvious way that companies can positively contribute to reducing biodiversity loss is to meet the growing consumer demand for new food products such as those that are protein-rich, plant-based, or contain superfood ingredients.

We are not going to cover this aspect for today’s blog for the simple reason that it's something that companies are already doing, for what are natural and normal commercial reasons. Other areas of possible action, which we will address in future blogs, are the challenging topic of meat (especially beef), plus regenerative production and upcycled ingredients.

For today’s blog I want to draw out two food ingredient case studies from a recent report prepared for the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). 👇🏾

We will not dig down into the economics of these changes in this blog, it's one for the future. But the EMF report suggests that the changes we will describe, taken together with other actions (a package they call circular design for food) , can actually increase farmers' profitability. Although it's worth noting that some of the changes involve material upfront costs, so assistance from the food producers, the buyers of the produce, will be important.

Most food we eat is designed!

The EMF report highlights that most of the food that is eaten is processed, to varying degrees. This means that it is designed. There have been very intentional and deliberate decisions made that determine the foods flavour, texture, nutritional content, appearance and of course its cost. This process does not have one single perfect outcome. Different decisions made in the food design stage can result in the use of very different ingredients.

So why not design it for lower impact as well

One way that this can produce better outcomes for biodiversity is through the selection of lower impact ingredients. What are they - these are ingredients that are conventionally produced, but that have significantly reduced environmental impacts as against their more widely used alternatives.

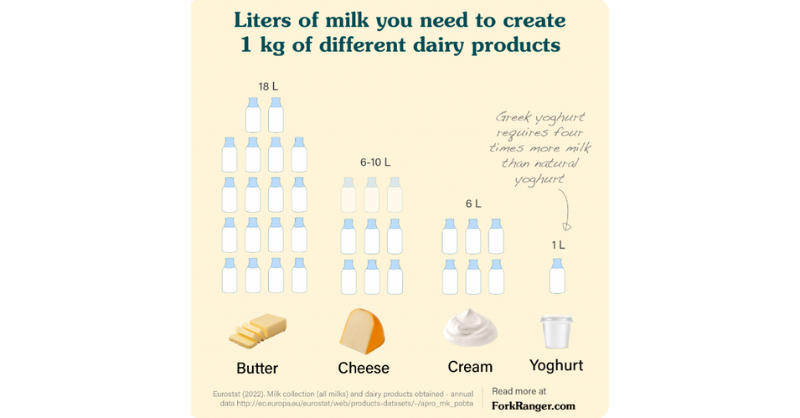

A example of this is cow's milk vs plant based milk. Milk consumption globally is predominantly fresh milk (including fermented and pasteurised) except in high income countries, where it's more tilted toward processed products such as cheese and butter. It's worth bearing in mind that Eurostat numbers (graphic from the Fork Ranger) show that butter and cheese require a lot more milk per 1kg of output.

According to the FAO, world per capita consumption of fresh dairy products is projected to increase by 1.4% p.a. over the coming decade, slightly faster than over the past ten years, primarily driven by higher per-capita income growth.

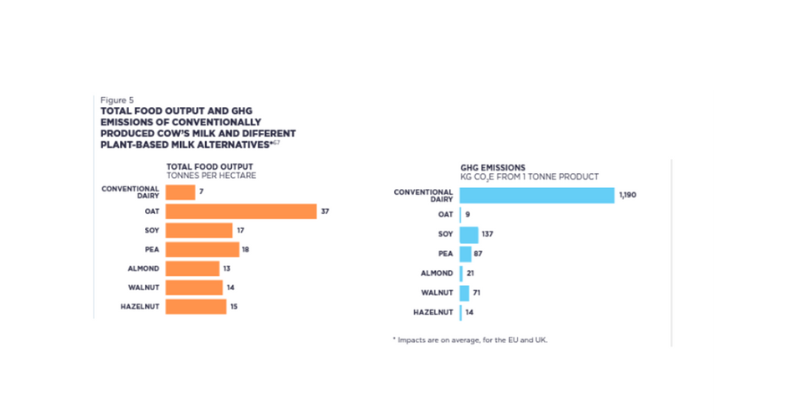

Looking at land use and GHG emissions, plant based alternatives use less land and produces materially lower GHG emissions.

But, reversing biodiversity loss is not just about reducing land use and GHG emissions. Issues such as water use are also very important.

A recent Cambridge University Press report highlighted that nuts, especially almonds, tend to be grown in water-scarce areas of the world and therefore increasing demand is causing depletion of water in already water-stressed areas. Similarly, as the demand for coconut milk increases so does the commercialisation of the cultivation of coconut. As we highlighted in a recent blog, concerns about biodiversity loss and deforestation from palm oil plantations have received a lot of attention. But the increase in coconut monoculture plantations is of equal concern in terms of land use, biodiversity loss and the use of fertilisers.

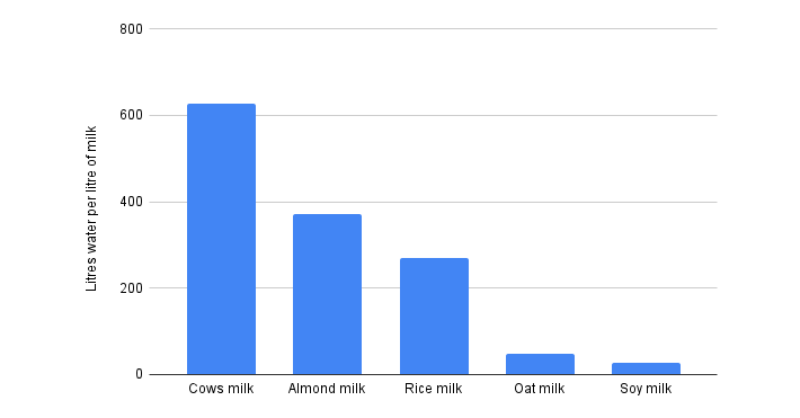

Digging down into the water debate a bit further - a 2018 study from a team at Oxford University summarised the water required to produce a litre of alternative milk.

Just to be clear on this data, there are a wide range of estimates on water use, some (such as the Water Footprint Network) put the water requirement for cows milk at over 1,000 litres per litre of milk, but as they point out, “the precise water footprint of milk in each specific case will depend on the place where and the production system in which the cow is raised, and on the composition and origin of the feed”.

So, circling back to the food design issue. If you are ahead of me, and I expect you are, then you are probably saying "raw milk is not a designed product". But yogurt, butter and cheese are.

Yogurt is estimated to be a c. $98bn global market, growing at c. 5-6% pa. And I can personally vouch for the fact that soya based yogurt tastes pretty much the same. This means switching formulations from cows based milk to plant based can positively contribute to halting and even reversing biodiversity loss (with the added benefit of cutting GHG emissions as well).

Food redesign changes using lower impact ingredients are fairly straightforward, the food manufacturer switches to a similar ingredient, but the end product is still similar. Another, slightly more complicated, way that food manufacturing companies can positively contribute to reversing or at least reducing biodiversity loss is to use more diverse ingredients.

Redesign using more diverse ingredients

Today, just four crops – wheat, rice, corn, and potatoes – provide almost 60% of the calories consumed globally. And, only a few varieties of each of these staple crops are cultivated at scale.

Diverse ingredients are those that come from a broad range of plant and animal species, as well as varieties within those species. They have similar characteristics as the more widely used ingredients, but for various reasons, often historic, they are not used in most food product design.

Using more diverse ingredients not only increases cultivated biodiversity within and between species, but also promotes biodiversity more broadly.

But, why should food manufacturers and food retailers bother?

One answer is that such an approach can actually improve the taste and flavour of the food. Many conventional crop varieties are selected for efficiency and yield, often at the expense of flavour or nutritional density. Food manufacturers have found that food that tastes better can achieve premium pricing - with a clear example being coffee, where specialist arabica blends sell for considerably more than standard robusta coffee. Who knows, switching to more diverse ingredients could actually push food to taste more like, well food.

Perhaps more importantly from a long term perspective, this approach can also enhance the resilience of the food system against threats such as pests, disease, and environmental shocks, and, as a result, enhance food security. 👇🏾

Pandemics are perhaps an extreme example, but then maybe not. But we do know that overreliance on a single variety can lead to entire crops failing. This can have serious consequences both for local communities and for the food producing companies. A recent example of this is Panama disease, which threatens the dominant Cavendish banana variety. This has parallels with the effective loss (as a commercial crop) of the then dominant Gros Michel variety in the 1950s.

Research also shows that climate change could cause global potato yields to decline by up to a third by 2060, unless diverse climate-resilient varieties are widely adopted. This has echoes of the disastrous Irish potato famines of the 19th century.

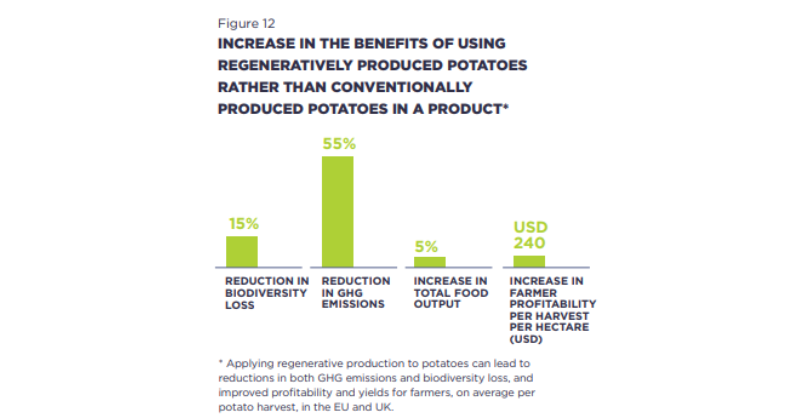

For crops such as potatoes that are particularly vulnerable to pests and diseases, shifting to more resilient varieties can provide significant benefits. For example, by replacing the common Maris Piper variety of potato with higher yielding potato varieties that are resistant to pests and diseases, synthetic fertiliser use could be reduced and land-use efficiency improved, leading to a 20% reduction in GHG emissions and 35% reduction in biodiversity loss, while at the same time increasing total food output by 60% in the modelled geographies.

And at a less dramatic level, diversifying livestock breeds may also bring benefits as certain breeds thrive in different climates and topographies. These include Pineywoods cattle, a breed more tolerant to hot climates, and North Devon Cattle that require little supplementary feed and may be more resistant to parasites and disease.

Another example relates to crops that add sweetness. This is currently mostly provided by just three crops (sugar beet, sugar cane and corn), whereas many diverse crops could be used instead.

Perhaps my favourite example of the possible use of more diverse ingredients involves peas.

Designing a wheat-based product such as pasta to use peas instead of wheat could reduce GHG emissions by 40% and biodiversity impacts by 5%, while increasing yields by 5% in the modelled geographies. Leguminous crops, such as beans and peas, can reduce the need for synthetic inputs by fixing nitrogen into the soil at much higher rates than many other cereal crops, at the same time as building soil health.

And this could be a quick and easy win. The EMF report estimates that:

“growing wheat and peas together using a set of practices that support regenerative outcomes can be profitable after just one year without any subsidies”.

Looking longer term, perennial grain varieties offer benefits. For example, perennial wheat (also known as Kernza or intermediate wheatgrass) is a variety, developed by The Land Institute in the US, that builds soil health as it doesn’t need to be tilled and re-sown after each harvest, unlike conventional annual wheat. Perennial wheat mimics native prairie grasses, with deep roots that absorb more nutrients and water from soils. It can sequester around 1 tonne of CO2e per hectare per year, which is about 10 times more than conventional wheat varieties. As yields improve over time, Kernza and other perennial grains and legumes could become viable substitutes for cereals in food products, with positive impacts on agroecosystem health and resilience

Conclusion

There are many actions that food manufacturing and retailing companies can take that can positively contribute to reversing the loss of biodiversity. Shifting to the use of lower impact ingredients, and the use of more diverse ingredients in product design will both be an important elements.

But, as we said at the beginning of this blog, there is no simple single solution, we need to push for a suite of changes. Some, such as meeting the growing demand for plant based foods, will be easier. But others, that require material upfront spending with longer payback periods, will be harder. These will need financial support. Moving to more diverse sourcing offers long term benefits for the food manufacturing and retailing industry - it's a solution that makes financial and value creation sense.

Why do we need to talk about this? As the Ellen McArthur report highlights:

“while 75% of food & agriculture businesses have made public commitments, only a handful have set out tangible plans”.

Which is where investors and their representatives come into it. We need to push for change, which means being better informed about the options, and their tradeoffs and consequences.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.