What caught our eye - three key stories (week 14, 2024)

Clean ammonia; industrial decarbonisation; the allure of consensus

Here are three stories that we found particularly interesting this week and why. We also give our lateral thought on each one.

Read in full by clicking on the link below.

'What caught our eye' like all of our blogs are free to read. You just need to register.

Please forward to friends, family and colleagues if you think they might find our work of value.

Clean ammonia - the decarbonised future of fertiliser

We know we need to decarbonise ammonia production. There are already technical solutions, including electrification, and the use of green hydrogen as a feedstock. In most cases they are not yet financially comparable, but they seem to be getting closer.

But in many situations decentralisation can also be a practical solution - moving the production of the ammonia (and nitrogen fertiliser) closer to the end user. Which is where alternatives such as that offered by We are Nium could be interesting. They are producing a modular nanotech-based alternative to the Haber-Bosch process. Technically a different approach, and so something to watch.

Ammonia is an important product from the chemical industry. It's uses are varied, from explosives to smelling salts to its current primary use: nitrogen fertilisers (80%).

The production of ammonia globally has a direct CO2e footprint as big as Brazil's! In terms of direct emissions, it is almost twice as emissions intensive as crude steel production and four times that of cement at approximately 2.4 t CO2 per tonne of production.

There have plenty of efforts to make ammonia production greener - something we wrote about in this blog 👇🏾

There are various ways in which ammonia's CO2e emissions can be reduced but is that all that matters?

We are Nium, which has a modular nanotech-based alternative to the Haber-Bosch process for making ammonia, commissioned Dr Claudia Gasparovic to investigate what clean ammonia on demand mean for natural systems - water, air and land? And how to eliminate emissions while minimising negative impacts on the environment?

Dr Gasparovic points out the huge potential for reducing emissions by adopting clean ammonia technologies - up to 490Mt CO2e in fertiliser and a further 250Mt CO2e in the urea supply chain.

Using a planetary systems lens she highlighted that there are some risks with deployment including nitrogen loss, land and water usage which counteract the emissions reduction impact.

However, she also points out that the choice of technology used, the sites and partnerships chosen can promote environmental health.

Here is Dr Gasparovic's LinkedIn post which includes the full report 👇🏾

We have discussed other modular green ammonia production systems in the past including this one from Talus Renewables in Kenya which generates clean hydrogen on site but appears to still use the Haber Bosch process👇🏾

The solution from We are Nium is interesting as it is an alternative to Haber Bosch and runs at a lower temperature and pressure. We shall watch with interest.

However, as well as reducing the 'dirtiness' of ammonia and ultimately fertilisers, we should also be reducing the amount of fertilisers currently used.

As Dr Gasparovic also points out in her report reducing CO2 and N2O emissions is the top of the pyramid of mitigation approaches, but we then need to reduce fertiliser use/loss and transition to a sustainable and even regenerative agriculture model.

Industrial decarbonisation - it's not just about cheesemaking

The US Biden administration has recently announced up to $6 billion in funding for 33 projects intended to curb carbon pollution from industrial facilities, including steel mills, cement plants and an Illinois factory where Kraft Heinz makes its well known, at least in the US, Mac & Cheese (for some reason the headline writers focused on cheese making)

As the Energy Secretary Jennifer M. Granholm said "these projects offer solutions to slash emissions in some of the highest emitting sectors of our economy, including iron and steel, aluminum, cement, concrete, chemicals, food and beverages, pulp and paper.”

If you want to learn more about the projects being funded - I highly recommend this podcast, from David Roberts at Volts. It's a longer one (over an hour) but it's worth the time.

Regular readers will know that we talk a lot about the need to decarbonise many of our industrial production processes. Why, because together they contribute roughly a third of our global greenhouse gas emissions. And on their own some of the big ones, such as steel making and cement production, are as material as transport. And yet they get a lot less attention (and money) than Electric Vehicles (EVs) and renewable electricity production.

Part of the reason for this is that some aspects of industrial decarbonisation are tough. They require materially different technologies and processes. This means for the companies involved the switch can be a big risk. They are reluctant to shut down an existing plant, which cost a lot of money to build, to replace it with a new, and some times uncertain, technology.

Which makes the '33 demonstration projects' really important. They get financial support to 'prove' that the new technologies can really work at scale. And by doing so, they de-risk the decision making process.

Let's take an example. I really wanted to use green steel (there are two big green steel projects on the list), but we have written on this a fair bit already. So let's use cement. The two that really caught our eye were the award of over $200m to Summit materials for a project demonstrating the potential of low-carbon calcined clay cement. And a similar project (with funding of $61m) in Virginia for Roanoke Cement.

What are these projects about? In simple terms they aim to reduce the use of limestone derived clinker in the cement we use. Most of the CO2 emissions generated from the cement production process come from the production of clinker. You can read about cement production in a blog we wrote back in may of 2023.

The challenge is not just the heat required to 'melt' limestone, the chemical process of turning limestone into clinker releases a lot of CO2. Limestone is Calcium Carbonate - we just want the Calcium to make cement, so the Carbon (the carbonate bit) gets bound to Oxygen and gets releases as yes, you guessed it, CO2.

What if we used less clinker in our cement? That would generate lower CO2 emissions. And it turns out that lower clinker cement can be just as strong as traditional cement. What goes in instead? It's calcined clay. Hence the pilot projects being funded.

This is a fairly new process at scale. Others are working on it as well, with Heidelberg Materials piloting calcined clay technology in Ghana, where the world's largest flash calciner is currently being built with a capacity of more than 400,000 tonnes per year. As Heidelberg says "in principle, a CO₂ reduction of up to 40% is possible when substituting cement clinker with calcined clay."

So, if this technology can be made to work at scale, then the cement industry will have a real way of reducing CO2 emissions. No-one is saying this is the total solution, it's part of a tool box.

We wrote about some of the other approaches that have potential in February of this year, following the publication of a major report by the Institution of Structural Engineers.

Link to blog 👇🏾

The allure of consensus

We all know that building consensus is the best way to drive change - but is it really? What if the consensus building approach is not the best way after all? Are there some cases where having a narrower but stronger support base is better? And what read across might this have for driving the sustainable transitions?

New research from the Kellogg School at Northwestern Univeristy, finds that people have a very strong preference for consensus-based persuasion strategies (broad but weak support) over extremity-based ones (narrow but strong support).

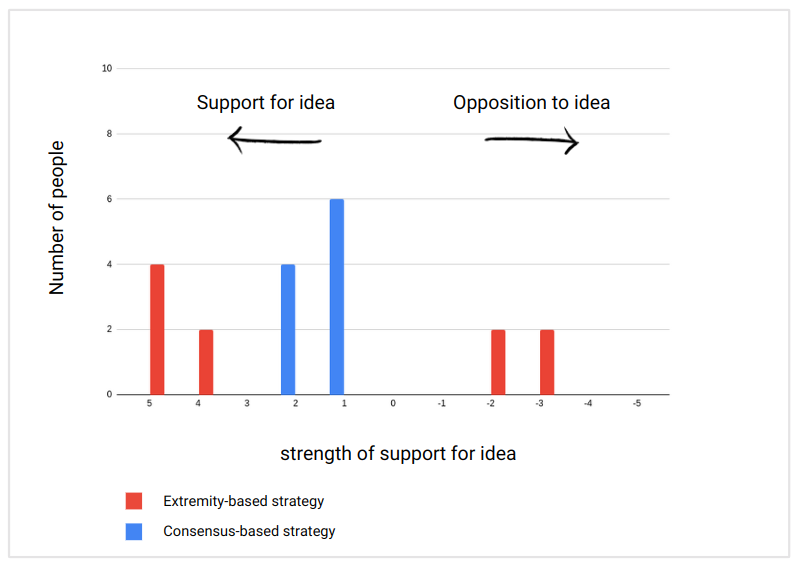

In the below chart, all 10 of the people in the blue group support the idea, whilst fewer people support the idea in the red group (6), but those supporters have stronger support for the idea on average.

A way to visual this is imagine trying to persuade a group of friends on a night out to go for a curry rather than a pizza. You could either get a low level support from the majority of people in the group to go for a curry or find a few people who say it's either curry or nothing.

Derek Rucker, a professor of marketing at the Kellogg School and leader of the study commented that “time and time again, people tend to gravitate toward getting more people on their side at the cost of having people who are true advocates.”

Why does this happen? Humans are social creatures and Rucker and his team postulate that we tend to enjoy group harmony - it feels more comfortable when a group is in general agreement than when there are strong voices on both sides of an issue. There is also a 'safety in numbers' element - even if that isn't true.

Clearly there will be occasions where a consensus based strategy is beneficial or even required (for example in a jury), but the problem that Rucker identifies is that because there seems to be an inherent preference for consensus, it can be misapplied.

To put that to the test, the researchers asked a group of participants to choose between two strategies for giving a speech to persuade a majority in a group of ten people to support an idea.

One strategy was a consensus-based one (with 8 people feeling somewhat positive and 2 feeling very positive); the other was an extremity-based strategy (with only 6 people supporting the idea, but with 5 of them feeling very positive). Note that both strategies met the objective of convincing the majority of people so either strategy would be right. However 86% chose the consensus-based approach.

To test how far the consensus would extend, they instead expressed the support of the people numerically (-5 to +5) with four different strategies, only one of which did not meet the goal of a majority in support. The other strategies had differing levels of extremity. To add a further element, half of the participants were told that a competitor giving a speech could reduce each audience member's support for the idea by 1-2 points. In other words, the strategy with the highest extremity was the one most likely to still show overall support.

In the half that didn't know about the competitor, 87.2% opted for a consensus-based strategy, but in the half that did know, two thirds of participants still chose the consensus-based strategy - even though it put them at a risk of losing!

With trying to persuade action in the sustainability transitions, we often try and go for consensus with an issue, rather than finding true advocates. However, sometimes the problem is that we are going for the wrong consensus. For example with home heating / cooling, if you try to persuade people to adopt new technologies with the promise that you would reduce their carbon emissions, you may get a varied response. However, if you instead promised it would reduce their cost to keep their homes at a comfortable temperature, I suspect, all things being equal, you would get consensus on that (and as an aside, we can reduce your carbon emissions).

And while at first only the strong advocates might buy in, over time the others will follow. You might recognise this as the S curve for innovation. Build a base among the advocates (first movers) and use that as a foundation to scale up.

We wrote about place-based approaches in this blog 👇🏾

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.