The ESG debate is becoming too simplistic

The sustainability and ESG finance debate has been oversimplified to the point where people have inadvertently over promised and under delivered.

Everything Should Be Made as Simple as Possible, But Not Simpler - attributed to Albert Einstein

Summary: The sustainability and ESG finance debate has been oversimplified to the point where many have inadvertently over promised (and under delivered). Investors have somehow been given the impression that by investing in positive ESG companies they can have it all - good financial returns, alignment with their values, and at the same time saving the world. All at no cost. That has also given ammunition to those who want to slow the process. Knowing the ‘what’ and ‘why’ of the requirement for investment helps one avoid green washing and green wishing (hoping that an easy and cheap solution makes the problem go away). Put simply, it allows us to better allocate our capital to projects that make a real difference.

Why this is important: If the language we are using is inadvertently confusing our shareholders/lenders and our clients, that is a dangerous place to be in an industry that relies on trust.

The big theme: The finance sector needs to support the sustainability transitions. We need to understand the real world complexity. Otherwise we end up investing our capital in projects that make little or no difference, other than to make us feel good - what economists would call a mis-allocation of capital on a grand scale.

The details

I spent most of my engineering career trying to make the complex real world (in my case earthquake engineering) simpler, more understandable. And I took this trait into my financial life, trying to reduce complicated investment cases down to the few really important things that we needed to understand. My best investing ideas were the ones where I could explain in simple terms what the market was misunderstanding (ie mispricing), and why there was a good chance that the future was going to turn out differently.

Given this, I never thought I would find myself saying we need to make things more complicated. After all, it's been drummed into all of us over the years that simple is best, that it helps people understand what it is you are trying to get across. Hence the frequent requirement that the pitch has to “fit on one page”, the “three bullet point” rule, and the “can you explain the investment case in under 1 minute” axiom in finance.

However, it appears that we have oversimplified the sustainability and ESG finance debate to the point where we have inadvertently over promised (and under delivered). And we somehow seem to have given our clients the impression that by investing in positive ESG companies they can have it all - good financial returns, alignment with their values, and at the same time saving the world. All at no cost.

This might all seem an odd position to take. After all, ‘ESG and sustainability’ are supposed to be the good guys. And, there is clearly a vast amount of complex work being done in the background. I am thinking here of projects such as the EU taxonomy, the SFDR and the work being done by Eurosif on the next iterations. But that is in the background.

By contrast, where the rubber hits the road, when we communicate with clients or shareholders or lenders, most of the time we use short hand - “I am an article 8 or article 9 fund” (or at least I was until recently), “I use ESG scores to create this passive ETF”, “the companies ESG score is 75%”, putting it in the top XX% of companies in its sector.”

Why does this matter?

The obvious answer is that if the language we are using is inadvertently confusing our shareholders/lenders and our clients, that is a dangerous place to be in an industry that relies on trust.

And, as a consequence, we have ended up giving ammunition to those who want to slow the process?

But there are some much more important reasons why this is a problem. First up, if we accept that the finance sector needs to act to support the sustainability transitions, then we also need to understand exactly how this can happen, which means we need to understand the real world complexity. Otherwise we end up investing our capital in projects that make little or no difference, other than to make us feel good - what economists would call a mis-allocation of capital on a grand scale.

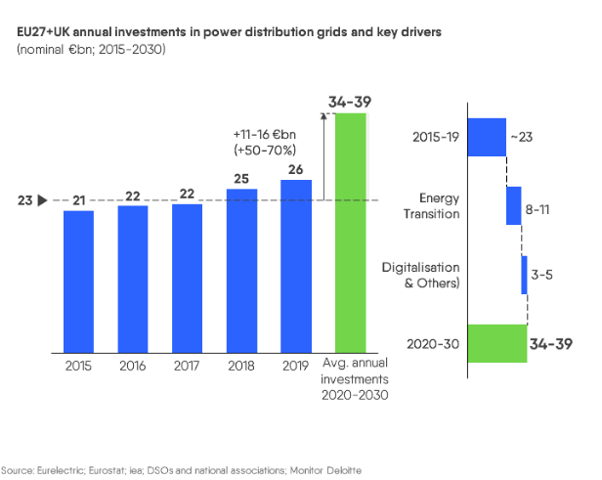

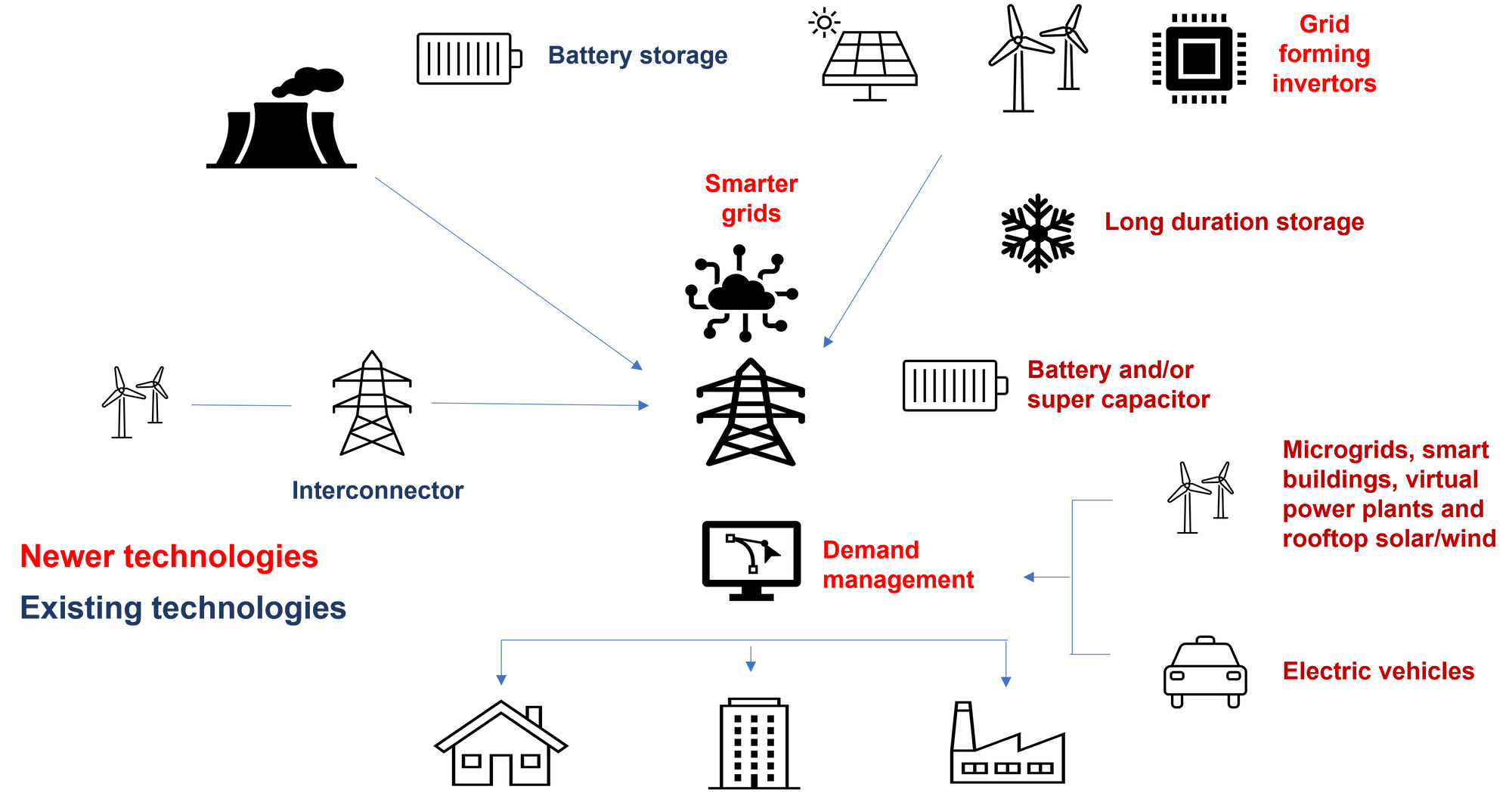

One example, which we will discuss later, is renewable electricity. Whilst building more renewable electricity generation is part of the answer, we also need to invest in a whole range of other activities. These include grid stability and enhancement, interconnector's, electricity storage and demand management. Otherwise our electricity grid will not be able to support high levels of renewables.

Understanding ‘why this is’ is technical, but it's an understanding that is worth building.

Knowing the ‘what’ and ‘why’ of the requirement for investment helps us avoid green washing and green wishing (hoping that an easy and cheap solution makes the problem go away). Put simply, it allows us to better allocate our capital to projects that make a real difference.

But, these are not the only reasons why we need a better understanding of the complexity of the transitions. Sticking with green electricity, we cannot leave the setting of policy to special interest groups. Doing so risks undermining the progress that can be made, as special interest groups look to bend regulation to support their aims. We cannot know what lobbying is good, if we don’t understand the issues.

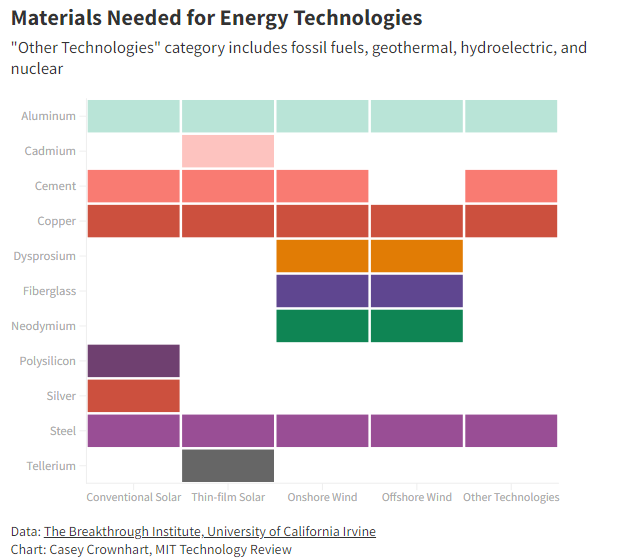

And then we have the really complex issues around sectors such as metals and mining. It's clear that we are going to need more rather than less mining. And given this, we want to make mining more sustainable.

This is again where it gets complicated. Yes, the challenges are solvable, but there are a mass of actions that need to be taken, covering issues as diverse as water, human rights, electrification, safety and environmental protection. It's currently too easy to say “mining is bad, I don’t want to invest in it”. But then the problems don’t get fixed. If we don’t understand the detail of what needs to be done, and the difference between good measures and green washing, how can we hold mining companies to account and encourage them to “do better”.

The good news is that a material amount of good work is being done already. Much of the task is to communicate it in a manner that helps asset owners, and their asset managers understand and apply it.

Let's dive into these further.

How have we got to this position?

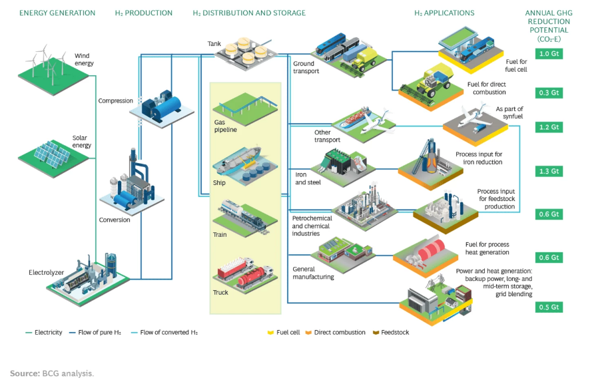

I get why this has happened. It's a widespread problem. For instance, politicians, the press, and other decision makers like simple messages and no pain/no cost solutions. And some lobbyists have taken advantage of this. A good example in the sustainability transition space is green hydrogen. It's a good solution to all sorts of challenging transitions. But it's currently very expensive (and it's hard to see this reversing until much later in the decade). And it's a really bad solution to challenges like home heating and passenger cars. These factors have not stopped many commentators talking up the opportunities, forecasting a green hydrogen boom.

Part of the appeal is the simple “let's just use green hydrogen to replace natural gas” message. Easy to explain, sounds quick, painless and cheap. And it allows us to avoid thinking about the complexity, the trade offs and compromises. Plus, it feels like we are doing something. Sadly, this is also leading to “binary responses' ' - green hydrogen is good, or green hydrogen is bad, leaving very little room for the required subtly around, it depends on the application and the situation.

To quote the author Mauro Guillen

“anthropologists and sociologists have long established that we manage the complexity of the world into categories. This enables us to sort things, develop strategies, make decisions and carry on with our lives. This allows us to retain the illusion that we are in control”.

For ESG and sustainability the categorisation tool that companies and investment organisations mostly use is ESG data. This has become a massive industry, rather rapidly. Harald Walkate, well known in ESG circles for his writing and his research at Zurich CSP, recently did a back of the envelope calculation, coming to a total yearly spend of between $50-100 billion. As he says, his number is probably wrong, but it's close enough in order of magnitude for us to know, this is a big industry.

But, the ESG and sustainable investing process was never intended to be solely data driven. ESG data, scoring and reporting is not an end in itself. No honestly it's not. Yes, data is important, but making financial decisions is about more than data. It's as much “art” as it is science.

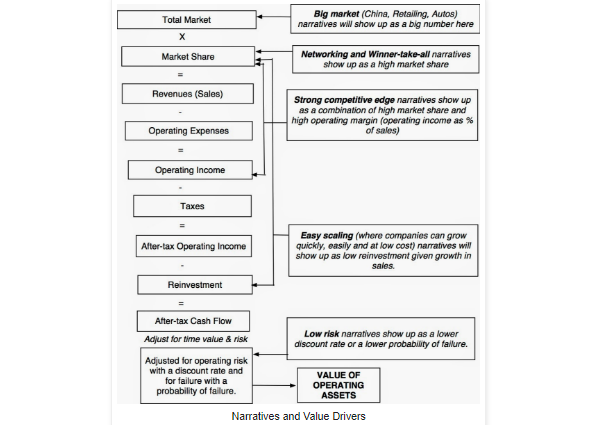

Good investing practice, and this applies to companies as well as investment managers, requires us to have a mental picture of how the world is, how it's likely to change, and how we can best contribute to, and prepare for, these changes. This is what shapes what data we use and how. To be clear, this is very different from telling stores, our financial narratives need to be firmly founded in reality. As Aswath Damodaran discussed in his influential blog, way back in 2014 (yes, it's not a new concept)...

Some commentators equate narrative to ‘strategy’. Regardless of what you call it, it's about the future, and the future is uncertain.

Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future! Attributed to Niels Bohr

This is a challenge that we face all the time when we build investment cases, either for the company we work for or in investment management. And, it was one of the toughest lessons to learn for the young graduates I mentored. Building investment cases requires data, but on its own the data doesn’t create good investment choices. We need to be able to explain, and test, our narrative about the future - what and why we think it will happen.

For now I want you to take something on trust. For many, if not most companies the future is going to look very different from the past. The so-called green revolution is coming. As with the last big shift, the internet, it's tough to predict exactly how quickly it will develop and which companies will be winners and losers, but we know that the old business models will fade and fail. And new products, services and business models will emerge.

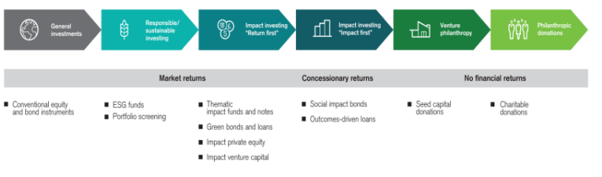

It's also clear that some providers of capital, the pension funds, endowments, family offices, charities and individuals, will have a much greater interest in where their capital gets put to work. Put simply, they are moving further to the right in the continuum that starts with traditional investing and ends with philanthropy.

And the same will apply to some companies, they will want to talk about different aspects of their investment cases, not just “this is my ESG score” and “here is the consensus financial forecast.”

This understanding is going to require us to go beyond the typical standard metrics we currently use. An ESG score, or expectations about future financials, will be only part of the story. Where should investments be made, in what technologies or systems or processes. What will drive the pace of change, and how quickly. Given the increased complexity inherent in the scenarios, with more tradeoffs, compromises and uncertainties, this is going to require a lot of client education.

But - who provides this education ? It might come from an investment manager, or maybe an individual company or industry group, although they need to watch potential conflicts of interest, the commentary needs to be independent.

And, for this education to be useful it has to have a clear narrative, an explanation of what it is we are doing, and why we think it will deliver the outcome that is targeted. And this narrative has to work with all of our stakeholders. So, for our clients (both advisory and financial), our customers & suppliers, our employees, our investors and lenders, and our wider community. It cannot be a sales pitch, it must be as honest a reflection of the challenges and opportunities we face as we can make it. What used to be called “warts and all”. If this is to work, we need to make this narrative more complicated, to better reflect the complexity of our real world financial decisions.

For this to work we need trust to enable us to build understanding

There was a good article in the FT on this topic recently. It wasn't a sustainability question. It was about a pretty dumb “explainer video” from the UK Chancellor (Finance Minister) on inflation. Leaving aside the cringe factor, the author of the article pointed to what Andy Halldane (the former Bank of England chief economist) called the “twin deficits' ' of understanding and trust.

He was talking about economists, but I suggest this also applies to the ESG and Sustainability industry as well.

Do we believe that our investment clients, the companies we work for and advise, and the general public, really understand sustainability? I don’t mean in some abstract way, to take an American phrase, like motherhood and apple pie. I mean in a very practical way. What it is trying to deliver and how. Or have we drifted into simplifying the process, such that the words we use either confuse the issue or even worse, over promise. And do they trust us to better inform them, or do they expect us to be selling them something ?

Low carbon electricity is not just about wind and solar

Let’s take a practical example that illustrates the complexity. One of the bedrocks of the sustainability transitions is, to use the words of Sydney-born inventor and founder of Rewiring America Saul Griffith, “electrify everything”.

A simple message that we can all understand.

And renewable electricity could, in the future, be cheap, potentially very cheap. To quote a Nesta study, the UK faces “ the prospect of abundant, clean, nearly inexhaustible energy”.

This is a message we see frequently. Wind and solar electricity is going to be very cheap, with some commentators talking about it being “too cheap to meter”.

Now, we (and by we I mean the scientists and engineers among us) know that this is only partly true.

Yes, wind and solar (especially solar) is likely to get very cheap. But, renewables will need a lot of battery storage, interconnectors and grid stability investment to allow them to work. And, we are going to need some sort of ‘back up generation’, for those days when there is not enough wind or solar - and this is going to be expensive. It might be keeping some gas fired power stations going (the cheapest option) or, if we want low carbon, it could be nuclear, or long duration storage, or pumped storage hydro. But none of them are cheap.

And then on top of this, we have the investment overlap. We, as a society, have spent a lot of money on our current, mainly fossil fuel based, electricity generation infrastructure. An unwritten rule of electricity regulation has been that in return for keeping the lights on, the electricity utilities will be allowed to generate a “fair” financial return on their historic investment. Without this “commitment” why would you invest billions of $ (or Euro’s or £). So as we build out our new renewables based (probably decentralised) electricity grid, we also need to continue to pay for what is already in place.

By now you will hopefully have got my drift, the next decade or maybe longer is going to be expensive. And if gas prices fall back to historic levels, they could be more expensive than keeping what we have now. This is not an argument for doing nothing, in fact we argue the opposite. In the long run this spending is our only viable option. But let's be honest about the cost.

And then of course there is the question of price. If wind and solar are going to be really cheap, how will investors make a financial return? After all, selling your product at very low prices, when you need to make a large upfront investment to build it in the first place, might be described by some people as foolhardy (we don’t think it will be, but it's a fair question).

Then finally, before we stop, what about the question of where these renewables will be built ? Not far from where I live, there are various organised campaigns to stop wind and solar farms being built. In the northern latitudes, where solar is more variable in its output, offshore wind is good, but onshore wind is cheaper. Either there will need to be some material political compromises, or we need to build expensive interconnectors to bring solar in from more southern countries. Is that good for energy security ? One halfway house might be to engage with local communities, not just giving them a token say but also some of the financial rewards.

Metals and mining - the devil is in the detail

I could have equally selected the debate around metals and mining. Without them most of the transitions will just not happen.

But to many sustainability specialists, and to a large section of the population, our stakeholders, mining is not green - but we will need a lot more of it, so we need to think about the best way of investing in it.

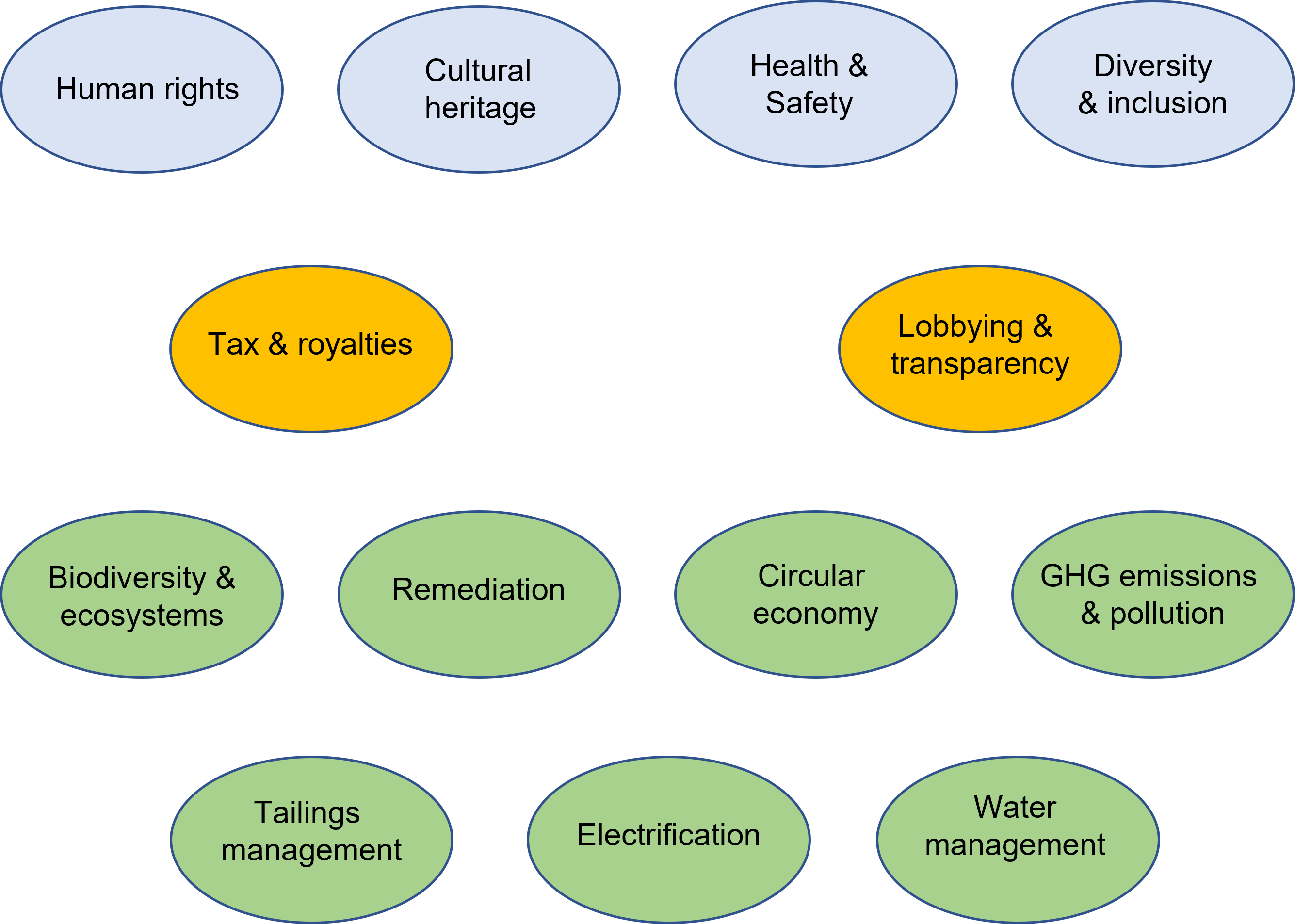

The challenge here is subtly different. There is not a simple alternative, one that has “does no harm”, while at the same time providing us with the raw materials we need for everything from electric vehicles, through greener buildings and transport, through to renewables such as wind and solar, and the vast amount of electricity grid investment we are going to need. Here the challenge is in the detail. What are mining companies doing now, and what can they do, in areas as diverse as human rights, worker safety, environmental protection (including water, pollution, dam tailings, and site regeneration), tax, electrification, recycling and the circular economy, plus of course transparency.

Conclusion

The importance of keeping things simple, of not over complicating, is drummed into anyone who works in the world of finance. The board presentation where no one understood the project, or the broker pitch where the client switched off long before the punch line, will always remain embedded in our memories, and not in a good way.

But sometimes we need to make things more complicated, avoiding the process of simplification that leads to our client taking away the wrong message, or picking the wrong investment choice.

Sustainability finance is just such as case. The choices we face involved uncertainties, and complex trade-offs and compromises - to navigate these we need more understanding not less.

Who is best to provide this independent view. It might come from an investment manager, or maybe an individual company or industry group, although they need to watch potential conflicts of interest. And ideally, the true providers of capital, the pension funds, the endowments, the family offices, the charities, and the HNWI’s, should get together and collectively financially support the push to a better understanding.

How might this happen? We probably need someone to take the lead, a family office or an endowment who says “this is a process that will help us all make better sustainability investing decisions.” Is this you?

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.