Sunday Brunch: Who pays matters

Funding sustainability cannot just be a debate about which funding source - we also need to understand how willing the end consumer is to foot the bill. Or putting it in simple terms, who pays. Because someone has to. And who gains? Is it always the same 'person' that pays?

The linear strategy fallacy says that if things aren’t working we just try harder. But reality is not like that - Glenn Geffcken (author and strategy consultant)

A conversation I have had more and more often is about where the money we need to fund the sustainability transitions will come from. This cannot just be a debate about which funding source - we also need to understand how willing the end consumer is to foot the bill. Or putting it in simple terms, who pays. Because someone has to. And who gains? Is it always the same 'person' that pays?

And this difference, when combined with the different timings of the costs and the gains, has become a material barrier to change. Especially at a time when politicians are happy to justify inaction by saying that 'they are helping people at a time when cost of living pressures are high'.

Does this mean we need a different approach? A number of the more advanced transitions (renewables and EV's) show that where we expose consumers to the full cost of the new technology, the practical support for it is low. But when governments bridge the financial gap, until the new technology becomes more cost competitive, the uptake is greater.

Which brings us back to the Glenn Geffcken quote. In a world of incremental change, with companies and consumers directly bearing the full costs but not seeing a material benefit, our sustainability strategies are more likely to fail. By that I mean we don't achieve the outcomes on the ground that we want or need. So, rather than trying harder, doing to same things but with even more intent, let's change the model.

To quote Einstein "the definition of insanity is repeating the same mistakes and expecting different results".

If you want to read the rest and are not already a member...

Who pays matters

I started off my working life as an engineer. Someone who built things that didn't fall down in earthquakes. I was 'lucky' in that I did most of this work in New Zealand. We had c. 20,000 earthquakes a year, of which c. 250 were big enough to be felt. So, not many people said 'this earthquake engineering stuff is expensive, building the traditional way is a lot cheaper, lets not bother'. We knew who suffered if we were unprepared when a big earthquake hit, we all did.

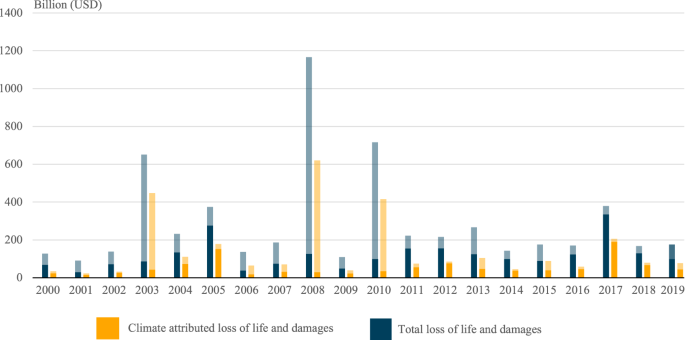

And we knew that by spending now, we made people safer, and we saved money in the future. And every now and then we had a reminder of the cost of failure. The Christchurch earthquakes of 2010 and 2011 cost c. "NZ$30 billion when ‘business disruption and additional costs from inflation, insurance administration or rebuilding to higher standards than before the earthquake’ are included". This is close to 10% of the countries GDP.

Many people present sustainable investing as being a bit like preparing for a major disaster such as an earthquake. It's a disaster that we 'know' is coming. The pressure is building up along the fault lines, giving us warning signs via a series of small quakes. And we know that one day the earth's crust cannot cope any more, and the fault line ruptures in a big one. The message is we should prepare for a major earthquake, rather than ignoring those warning signs.

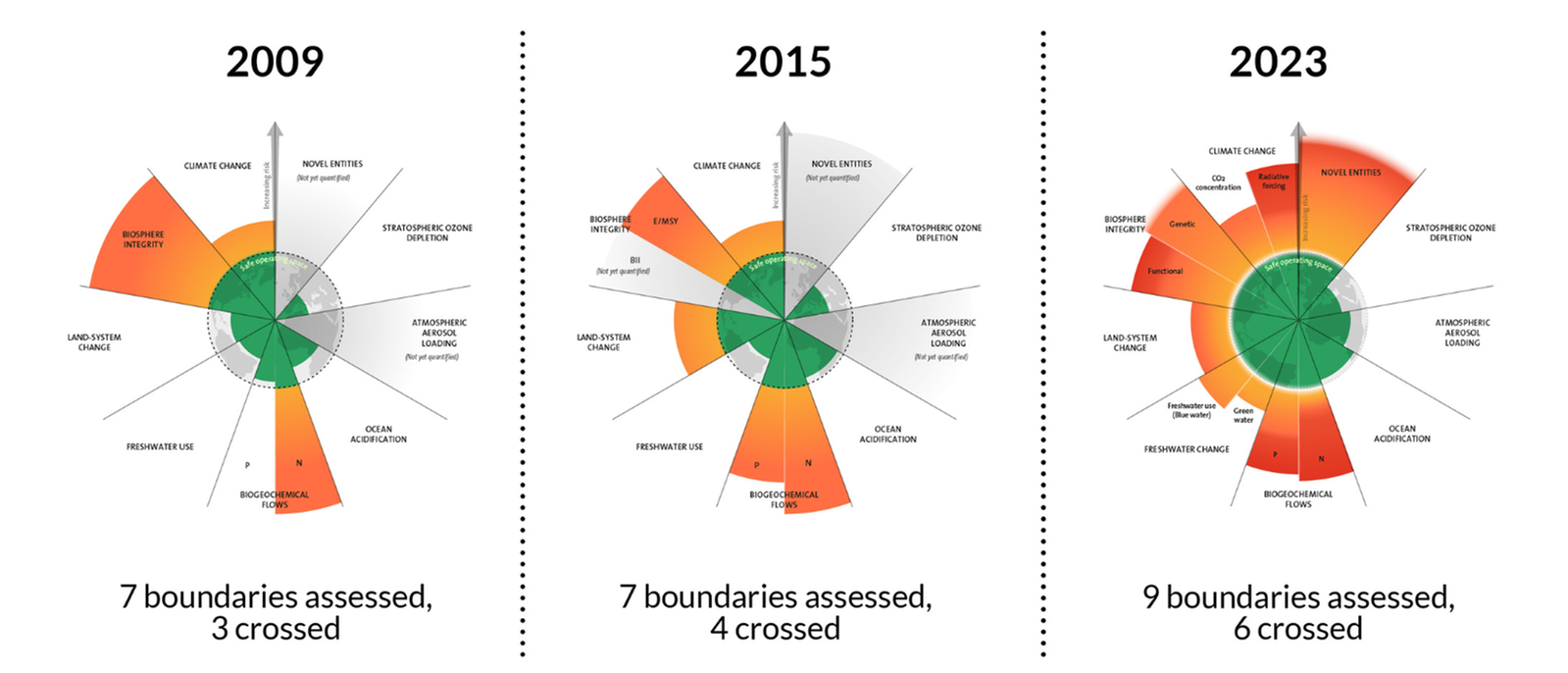

In the case of sustainability, as we breach the planetary boundaries, we get closer and closer to the point at which the cost of the disaster massively exceeds what we would have spent on mitigation, if we only started soon enough. And the current acceleration in natural disasters - floods, hurricanes and droughts, is our set of warning signs.

But there are a few material weaknesses in this analogy. First, many of us have experienced large earthquakes, even if only on TV. But most people struggle to understand what a 3 or 4 degree world would look like. We have no relevant experience.

Second, at least in those countries that have earthquakes, the consensus is that avoiding earthquake damage is a good thing. But this consensus doesn't really exist around the sustainability transitions.

And third, in earthquake prone countries, we all benefit from spending on making buildings stronger. But for many people there is a sense that they are paying more than their fair share of the costs for the sustainability transitions. And not really seeing any tangible gains (yet).

Many groups cannot justify paying the cost

We talked about this recently in the context of farming. It's really important for our wider society that farmers change how they farm. And we, by and large, know the solutions. But who pays the upfront costs?

We argued that many individual famers, who operate in an extremely challenging business environment, are unable to justify the risk of taking action, and it not working out. Which means we need others in the supply chains, with deeper financial pockets, to take some of the financial load. This could be global food producers, or food retailers, and of course, the ultimate end payer, the consumer.

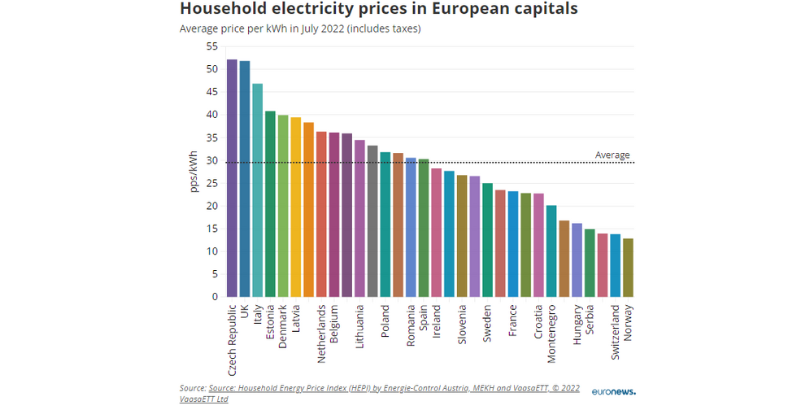

Another example of this is renewables, where some countries (such as the UK) make the consumer pay the higher cost of electricity, as the electricity system transitions. Yes, we know that the transition is important, and we know that at some point we will benefit financially from the new renewables based system. But, in the medium term we just pay more, sometimes a lot more.

In this situation, it should not be a surprise when consumers and companies do not electrify. Even if it's the right thing to do, in the long term.

Being up front about who pays, and when we gain, matters

There are a broad range of cost estimates for how much it will cost us to reach net zero by 2050 (which is just an element of the wider transition we need to make). The lowest estimate I have seen is c. $3.5 trillion pa (the Network for Greening the Financial System), through to $4.5 trillion pa from IRENA, and on to $5 trillion pa from BloombergNEF.

And what if we don't spend this money. The science is pretty clear that human habitation will be materially impacted, potentially taking us well past many, if not all, of the important planetary boundaries. And even if we just focus on the costs of climate change damage, a recent World Economic forum report, partly based on a study published in Nature, suggests a direct cost of between $1.7 trillion and $3.1 trillion by 2050.

So, at a societal level, acting seems by far and away the better solution. But do we have a mismatch between who pays and who gains, plus an issue with when we pay and when we see the benefits?

Who pays and who gains, and when?

If we go back to the detailed McKinsey report of January 2022, we can look at what the transition will cost, how front end loaded they are, and when the gains start to come through.

Picking out some examples. Total capital spending would need to increase from c. 6.8% of global GDP to about 9% between 2026 and 2030, before it starts to fall back.

And the delivered cost of electricity (which we discussed above) could rise about 25 percent from 2020 levels until 2040 and still be about 20 percent higher in 2050. If companies and consumers have to pay the full cost of this, will they really electrify. Or will they wait until they actually see electricity costs begin to fall back ?

This is not a plea to allow companies to continue to pollute our environment, or even for them to be given financial aid to stop. It's more about the recognition that some sustainability transitions require material upfront spending, and that the benefits often don't go to those expected to pay the cost. For many companies and consumers, the direction and pace of political, social and regulatory change is not yet clear enough for them to justify a step into the unknown'.

Let's remember that when we lobby companies and encourage consumers.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.