Sunday Brunch: sizing up good corporate governance

Improving overall corporate governance can improve valuation, but what should we be looking for?

In a recent edition of 'What Caught Our Eye' we discussed a meta analysis from Nguyen and Dao from Hanoi University that looked at the impact of improving overall governance on stock valuations compared with improving liquidity - often achieved by listing a company's shares on a liquid exchange with lots of traded volume.

'Spread' = the difference between the bid (the highest price someone wants to pay to buy a stock) and the ask (the lowest price a seller will sell the stock). The smaller the spread, the more liquid the stock.

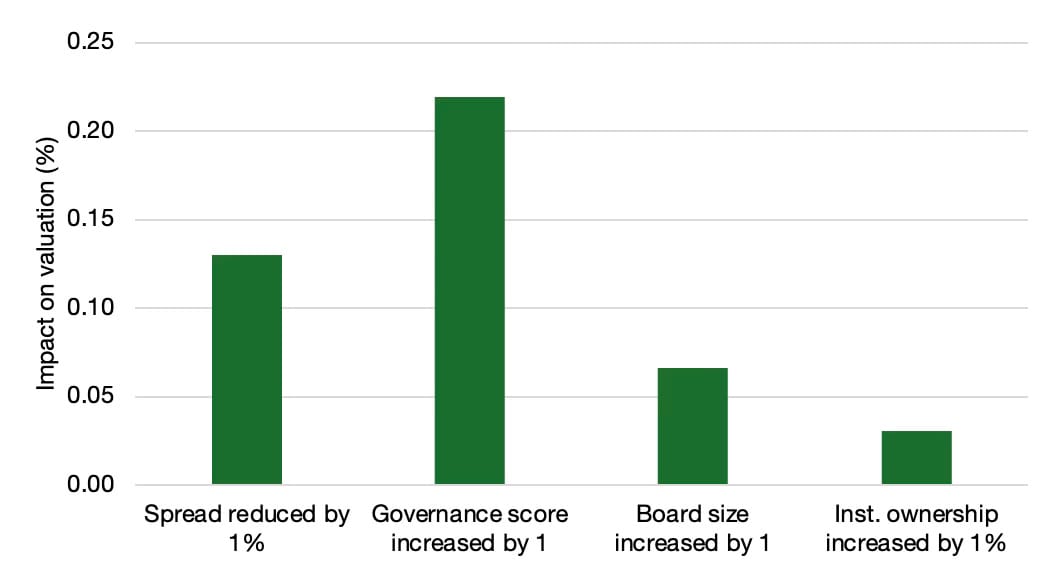

They found that improving overall governance had a positive impact on valuation. In fact it had a bigger impact on valuation than improving liquidity. The chart below illustrates this.

What the chart also reveals from the study is that improving overall governance had a much bigger impact than individual governance measures alone - for example, simply increasing the size of the board. In fact in this case it had 3x the impact.

So we need to think about governance of organisations, or 'corporate governance' holistically and it raises a broader question: what makes up good 'corporate governance'?

And before that, what is 'corporate governance'?

If you want to read the rest and are not already a member...

What is 'corporate governance'?

Let's start by looking at a few different definitions starting with a basic high level one.

The Cambridge Dictionary definition of 'corporate governance' is the "way in which a company is managed by the people who are working at the highest level in it."

The Chartered Governance Institute UK & Ireland describes corporate governance as:

"... the way in which companies are governed and to what purpose. It is concerned with practices and procedures for trying to ensure that a company is run in such a way that it achieves its objectives."

Chartered Governance Institute UK & Ireland

They go further to say that from a shareholder’s perspective, "corporate governance can be defined as a process for monitoring and control to ensure that management runs the company in the interests of the shareholders." They also highlight that there are other groups, including employees, customers and the general public who will an interest in how a company acts.

The Corporate Governance Institute goes further to say that the purpose of good governance is ...

"...to ensure that businesses have the appropriate decision-making processes and controls to ensure that all stakeholders’ interests (shareholders, employees, suppliers, customers and the community) are balanced."

Corporate Governance Institute

Historically there have been 'signs' of good governance and suggested best practices. The most familiar ones tend to be at the highest level. Examples include separating the roles of chairman of the board and CEO, increasing the size of boards and increasing institutional ownership.

In a 2015 Harvard Business Review article, Guhan Subramanian (Joseph Flom Professor of Law and Business at the Harvard Law School and the Douglas Weaver Professor of Business Law at the Harvard Business School) proposed a back-to-basics reconceptualisation of what good corporate governance means - Corporate Governance 2.0. He put forward 3 principles, aimed at US public companies, but applicable more broadly:

- Principle 1: Boards should have the right to manage the company for the long term.

- Principle 2: Boards should install mechanisms to ensure the best possible people in the board.

- Principle 3: Boards should give shareholders an orderly voice.

I started my financial career at professional services firm Price Waterhouse (now PwC) qualifying as a chartered accountant and member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW).

The ICAEW has this to say about the purpose of corporate governance:

"The purpose of corporate governance is to facilitate effective, entrepreneurial and prudent management that can deliver the long-term success of the company."

ICAEW

So Professor Subramanian's 1st principle aligns with that 'long-term success'. In a recent Sunday Brunch, we looked at whether directors are properly discharging their fiduciary duty by taking into account the changing landscape in which they operate? In other words taking into account future risks and opportunities in their decision making including systemic risks. The long-term. Are they using foresight? Arguably ensuring the best people are on the boards should, in theory, help with that too (principle 2)👇🏾

The 3rd principle is focused on shareholder voice, but of course since 2015 we have seen an increased awareness and focus on other stakeholders. Regular readers of The Sustainable Investor will know that we look at 'sustainability' from its base definition - the ability to last for a long period of time. Alex Edmans, Professor of Finance at London Business School, commenting on Milton Friedman's seminal 1970 New York Times article, pointed out that Friedman had argued that "it is legitimate for a company to focus on increasing profits because the only way it can do so, at least in the long term, is if it treats stakeholders seriously." Friedman actually wrote, “It may well be in the long-run interest of a corporation that is a major employer in a small community to devote resources to providing amenities to that community or to improving its government. That may make it easier to attract desirable employees.” In order to be able to last for a long period of time one must consider all risks and opportunities and that inevitably will entail consideration of all stakeholders.

So in summary, good corporate governance should have well documented and understood practices and procedures, facilitate long-term thinking and consideration of all stakeholders for the benefit of the long-term success of the company.

All about the board right?

Back to that Cambridge Dictionary definition: "the way in which a company is managed by the people who are working at the highest level [our emphasis] in it."

You will also have noticed a common word starting each of Professor Subramanian's three principles: Boards.

But is good corporate governance the preserve of the board or rather is the board the only place to identify the signs of good governance?

Back in my PW/PwC days on audit jobs, one of the big tasks was the review of internal controls. The purpose of an audit is to form a view on whether the financial position of a business at a particular point in time is fairly reflected in the financial statements, when taken as a whole. In conducting an audit, we had to get a good understanding of the business's activities, the economy and industry in which it operated and the risks the business faced - those risks are where the internal controls come in: the processes and measures that the business has to mitigate those risks. The review was identifying and assessing those to see whether they could facilitate the ability of the business to present a true and fair reflection of the financial position of the company. These internal controls pervaded the business across many different levels of seniority (and juniority).

Even broader than internal financial controls, ISO standards are designed to ensure the quality, safety and efficiency of products, services and systems. At Curation where I was CEO, we attained ISO 9001:2015 certification. Applying for it and then maintaining required a lot of effort from pretty much everyone at the firm. But we saw an almost immediate improvement in the efficiency with which the business operated - fewer errors, better working capital management, better decisions - which became crucial as we scaled.

Governance starts from the top - at the board level - in setting the culture of the company, but execution is key.

Dr Mimi Ajibade, founder of Cogent Governance, wrote an excellent article highlighting the unsung heroes of corporate governance - company secretariat. This is particularly acute at year-end and period-end.

"Year-end housekeeping within the company secretariat is not just about ticking off administrative tasks; it's about upholding the pillars of sound corporate governance."

Mimi Ajibade

Reviewing annual reports and financial statements, maintaining an accurate group structure chart and subsidiary list, properly managing the company's shareholder structure, recording and maintaining board minutes and ensuring the company complies with all relevant laws and regulations. These tasks and responsibilities absolutely underpin a good governance culture.

Execution is key to a culture of good governance. Operational governance is often overlooked.

[We shall be exploring the topic of operational governance in an upcoming blog featuring insights from Mimi Ajibade]

Does governance even matter?

Stuart Kirk, FT journalist and former Global Head of Responsible Investments at HSBC, writing in January 2024 postulated that "... we are all hypocrites on corporate governance." He went further to suggest that governance doesn't matter. What?! How can that be?

Alex Edmans, in critiquing Stuart Kirk's article, highlighted research from Giroud and Mueller (2009, 2011) that when industry competition is high, executives still need to be at their best even if protected by, for example, dual class shares that stop them from being kicked out. Having skin in the game, even in the absence of good firm governance still provides a strong incentive, according to work from Von Lilenfeld-Toal and Ruenzi, (2014)

So sometimes governance doesn't matter right? Well... it's not that it doesn't matter in the above situations, but rather as Von Lilenfeld-Toal comments, that it can "mitigate the negative impacts of weak governance."

Good governance should still be the aim for the long-term success of the business.

Back to governance and stock valuations

A paper from Bebchuk, Cohen and Wang (2012) found that the correlation between stock market returns and governance largely disappeared in the 2000s not because good governance stopped being important for companies, but rather because investors had become better and identifying it and pricing it in. Remember stock market trading is about expectations asymmetries. Events happening that are not as expected will cause share prices to move. If it is already expected.... snooooooze.

But good governance should matter to directors as it can potentially increase the value of the companies that they have responsibility for (and sometimes liability for) - as the work from Nguyen and Dao suggests. It will do more than simply aiming for better stock liquidity.

And as Joachim Klement pointed out "...unlike trying to increase liquidity, it [governance] is a measure that is entirely under the control of executives and their boards."

Individual governance measures are not enough. There has to be a culture of governance with strong pillars.

But the pillars of good governance also exist beyond the board.

Operational governance is an area we shall explore in future blogs.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.