Sunday Brunch: premiumisation as a sustainability strategy?

Your premium brand had better be delivering something special, or it's not going to get the business.- Warren Buffett

Can a premium coffee brand help the farmers ?

People who know me know that I love coffee. But, we have to accept that as an industry, it has some sustainability issues. One is climate change, which could impact where good coffee can be grown. The other is poverty among the coffee growers. Don't think that the price of your cup of coffee in New York or London reflects what the farmers get paid. For this second aspect to change, we need to rebuild how industry profits are split. or in finance speak - we need to change the value chain.

One question I have been pondering is - could creating local/regional premium coffee brands help the industry with it's sustainability issues? And could this act as a template for other agricultural/natural capital challenges?

Our view - A vast industry exists that takes agricultural products and turns them into food and beverages. Many of these are commoditised - with limited differentiation. And in many other cases the branding value is held by the end retailer or the processor. As a result, the farmer or grower often only sees a small percentage of the final retail price. And this can make it difficult for them to raise the capital they need to invest in more sustainable production methods, higher yields, or to improve the quality of their production. Which in turn creates a negative feedback loop.

Premiumisation can be part of the solution - creating a product that can be sold at a higher price, with the farmer capturing a higher share. But as Warren Buffet says, to be premium the product needs to offer something special.

One crop that seems to offer potential in this regard is coffee. Premium coffee, grown in specific regions, is very different from the mass market product. Could this be part of the solution to improving the livelihoods of the farmers? If this is an idea you would like to explore further - get in touch and we can introduce you to some experts.

Can we create coffee premium brands to help the farmers?

We all know about the pricing power of premium brands. How customers pay up for everything from luxury handbags, through alcoholic beverages such as cognac, scotch and champagne, to premium foods such as Parma ham, truffles, and wagyu beef. Having spent many years analysing what makes a premium brand truly valuable, I wanted to explore how premiumisation could potentially work in coffee.

At a high level, it looks encouraging. As a lover of good coffee, I know that the best coffee from specific regions has very distinctive characteristics. It's materially better than mainstream coffee. This gets us over the first hurdle, what we could call the Warren Buffet test. Does it deliver something special? Yes it can.

Before digging down a bit more, it's important to be honest. Creating a premium coffee brand will not, on it's own, solve the problems. And, it would not be easy. But, when taken together with all of the other actions being taken by industry groups, it will positively contribute. As always, there is not a simple single silver bullet.

What is the coffee growers challenge?

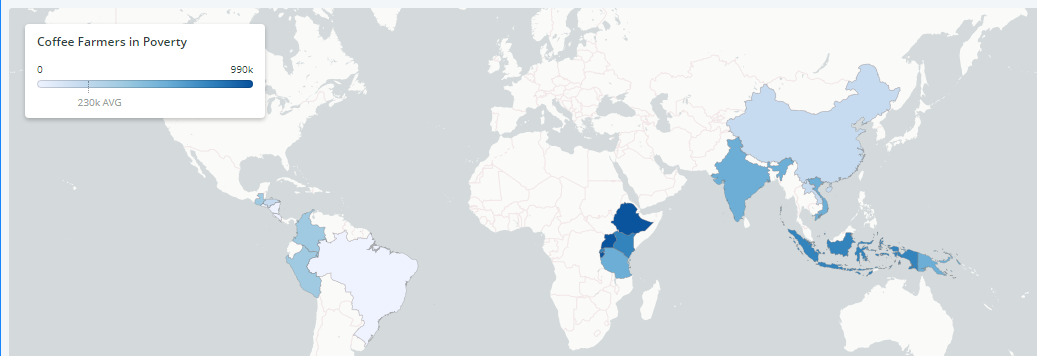

Put simply, it's poverty. Many coffee growers struggle financially. As we highlighted in a recent blog on coffee 'waste', close to 60% of global coffee production comes from farms of less than 5 hectares, often in remote areas.

According to Enveritas, as of 2019, 44% of the world's smallholder coffee farmers are living in poverty and 22% are living in extreme poverty. The majority of coffee farmers living in poverty are concentrated in six East African countries. These countries account for approximately 63% of the world's coffee farmers living in poverty and 71% living in extreme poverty. The region is characterized by low coffee yields that result in low income to these farmers.

In addition, the majority of smallholder coffee farmers lack access to high-value markets for sustainable coffee. Many of the actions needed to reverse this relate to providing the farmers with tools to improve production yields, but other relate to the economics of verifying what the farmers are doing on the ground.

Creating premium brands is tough

Our challenge is that we don't just want to create a premium coffee 'brand' (like Nespresso). We want to create one that benefits the farmers, a 'Fair Trade' on steroids.

Many agricultural products have a premium branding tier. We pay more for a product from Ben & Jerry's or Coca Cola. But, the problem with these examples is that the branding is 'owned' by the food production company. The farmer is still largely a commodity supplier. In coffee, how many of us even known the country of origin of our Starbucks coffee (just picking a brand at random). And while many people buy very specific Nespresso pods, this doesn't get down to the grower level.

There are a couple of reasons for this. First, and most obviously, creating a food or beverages brand requires the product to be different. Not many products are really different. Think yogurt. Yes, we have yogurt brands, but true differentiation is tough. So we end up with what you could think of as mainstream brands, they have a price premium but it's small. Now compare yogurt with scotch. Premium scotch has a massive brand premium.

Second, creating a brand, such as for a scotch, is expensive and time consuming. As a result, companies want to keep control of their brands. And that is harder when some of the characteristics that make the brand premium in the eyes of the end consumer, come from the farmer.

What steps do we need on the path to premium branded coffee?

Parking for a moment the process of marketing a premium coffee brand, a key earlier step is creating the 'something special', the guarantee that the coffee actually comes from a specific region and that it meets minimum standards. Before exploring how this can be created, I want to discuss an example that has gone wrong.

Manuka honey is known for its many health benefits. There are various grading systems that exist to protect standards, of which the best known is the Unique Manuka Factor grading system or UMF. Under this the honey is tested for all three of its naturally occurring chemical markers (Methylglyoxal, or MGO, Dihydroxyacetone, or DHA, which indicates the age of the honey, and Leptosperin, which is only found in genuine manuka honey).

To receive UMF grading, manuka honey must be from New Zealand, and tested, packed and labelled in New Zealand. But clearly something has gone badly wrong, as the world is buying more manuka honey than is being produced.

At the heart of the scandal: basic maths. According to New Zealand's leading manuka honey association, 1,800 tonnes a year of the honey are now consumed in the UK each year, out of an estimated 10,000 tonnes globally. Yet production of the genuine stuff is just 1,700 tonnes. Setting up a grading system on it's own is meaningless, if its open to abuse and profiteering.

So, what examples can we use where standards and branding have worked. And preferably worked for the benefit of the producer/farmer. There are a couple of precedents that could help us in this process. The first is co-operatives, and the second is appellations & protected region of origins.

Starting with co-operatives. I first came across the champagne co-operatives around 20 years ago. Their cooperative business model is built around the pooling of resources, knowledge and outcomes. In this case they act for the champagne grape growers. They help spread best practice and many cooperatives have created their own brand. Some brand names are well-known, especially at national level. And others have carved out a place among the world’s best-selling Champagnes.

The real strength of the system is in the co-operation between the big champagne houses and the growers. They both need each other. Without the growers, there is no champagne industry, and without the big brands, champagne would be a lot less premium than it is. There is an understanding of mutual interest.

Appellation's are slightly different. They refer to a legally determined and protected region of production. The appellation sets standards, and in return, the consumer knows (as much as practical) what quality they will get. We mostly know appellations in wine. Protected Designations of Origin (PDO) go further. This is very much a European concept, where only product from a specific region can use the brand name. To use the PDO, every part of the production, processing and preparation process must take place in the specific region. The next level down is a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI). Under this at least one of the stages of production, processing or preparation takes place in the region. Examples include Italian balsamic vinegar from Modena, Dutch Gouda cheese and Bermet desert wine from Serbia.

Unlike the manuka honey producers, the Champagne co-operatives, the appellations, and the Protected Designations/Indications, jealously guard their brand. They use trademarks and international trading agreements, backed up where necessary by legal action.

Cost is probably the biggest barrier

Let's be clear, none of this is going to be easy, or cheap. Branded consumer goods companies such as Nestle spend vast amounts of money, and incur significant legal expenses, in creating, building and protecting their brands. For a grower led premium coffee brand to work we will need governments to commit to supporting and enforcing standards, plus the growers need to work together. And we will need some form of the champagne co-operative structure, where roasters and growers work together. And, it will probably need a distributor, an organisation with a global reach who can market the product, and get it to the consumer.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.