Sunday Brunch: the flaw of averages part 2: personalised medicine

Drugs produced for the 'average person' don't always work for everyone. Are we finally starting to leave the world of one size fits all, and heading toward personalised medicine and diet?

The notion of 'one size fits all' should be a nonsense. The good news is that, in the field of health and medicine, we are seeing a gradual if slow trend from everyone getting the same treatment, to you being part of a group, right down to personalised medicine. The starting point for this is meaningful clinical trials.

But, it now goes further than that. One example is using your own immune system to be trained to recognise and attack cancer cells. Plus, there is much that can be achieved from a preventative and curative perspective from changing what we eat. However, as with medicine, there is not one diet that is the best for all. Diet is very personal. Our bodies react to different foods in different ways.

Are we finally starting to leave the world of one size fits all, and heading toward personalised medicine and diet?

One of the first recorded clinical trials took place in 1747. Scurvy was a big problem, particularly for sailors and naval doctor James Lind decided to investigate. He took 12 scurvy sufferers on a ship, divided them into pairs and gave each pair different treatments from vinegar to cider to sea-water to citrus fruits.

The pair eating the citrus fruits recovered 'proving' that citrus fruits could cure scurvy. Going forward the British navy started storing limes and lemons onboard and giving them to sailors to ward off scurvy. It's where the American nickname for Brits comes from - 'limeys'.

We now know that scurvy, a condition of malnutrition is caused by a lack of vitamin C and that citrus fruits are rich in vitamin C.

Of course, today clinical trials are more sophisticated and have bigger sample sizes.

The main aim of clinical trials is to look at the efficacy (does it work), side-effects (undesirable effects) for an 'average group' in a trial and apply that to the broader population. A couple of years ago I had some athlete's foot. Not a particularly debilitating condition, more of an annoying one. It was particularly stubborn and the usual creams had not worked and so I was prescribed the oral anti-fungal Itraconazole. Just under three weeks later I was in hospital being checked over in the emergency room as my liver function had collapsed. A rare occurence at such an early stage in the treatment course. But a probability of 1 for me!

We have discussed before how the notion of an 'average person' can be an inherently flawed concept unable to account for human complexity. The 'flaw of averages.' 👇🏾

Real world Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

One important diversity, equity and inclusion issue in healthcare is that of having access to healthcare that works for you. There will be physiological differences between population groups from ethnicity to gender to age. The healthcare solution you are offered should recognise these differences.

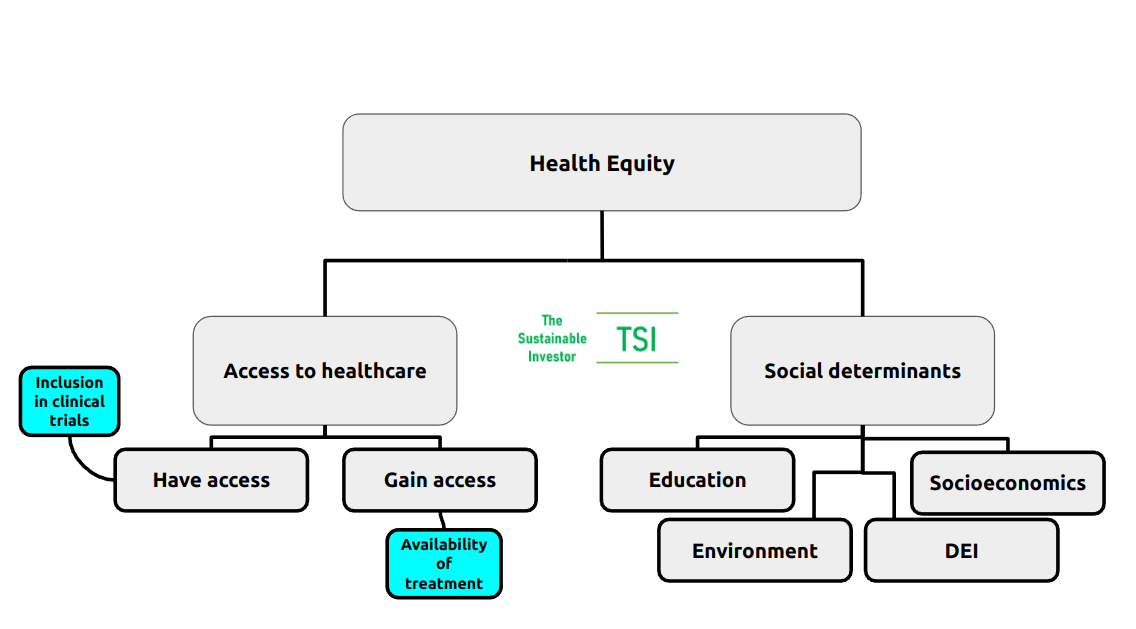

We produced a deep dive on the topic of Health Equity which you can read here 👇🏾

From a group to the individual

But what about going even further than individual groups right down to the individual? Given that everyone is different, one drug may elicit different reactions not just between groups of similar people, but between individuals themselves.

Let's make it personal.

Get you working for you - cancer treatment

Elliot Pfebve, a 55 year-old cancer patient from Birmingham had already had surgery and chemotherapy to treat his bowel cancer but there were still cancer cells remaining in his body - there is always a risk of this and essentially why the condition can recur.

At the end of May 2024, Elliot became the first patient in England to be treated with a personalised vaccine against bowel cancer and the first in what is expected to be a thousands of patients participating in an NHS trial.

A small sample of Elliot's tumour was sent to BioNTech, a German biotech company which produced one of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines, to identify proteins that could trigger an immune response - i.e. Elliot's own immune system would be trained to recognise and attack cancer cells from his tumour. The vaccine was co-developed by BioNTech and Genentech.

In June of 2023, a small clinical trial of a personalised mRNA-based vaccine against pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), which accounts for over 90% of pancreatic cancer cases, demonstrated a strong tumour-specific T-cell response in half of the trial participants.

Treatments personalised for an individual.

What is 'mRNA'?

The vaccines mentioned above are mRNA vaccines. How do they work? what is 'mRNA'?

We introduced some of the structures and mechanisms in the human cell previously. If you are unfamiliar with the basics it's worth a review👇🏾

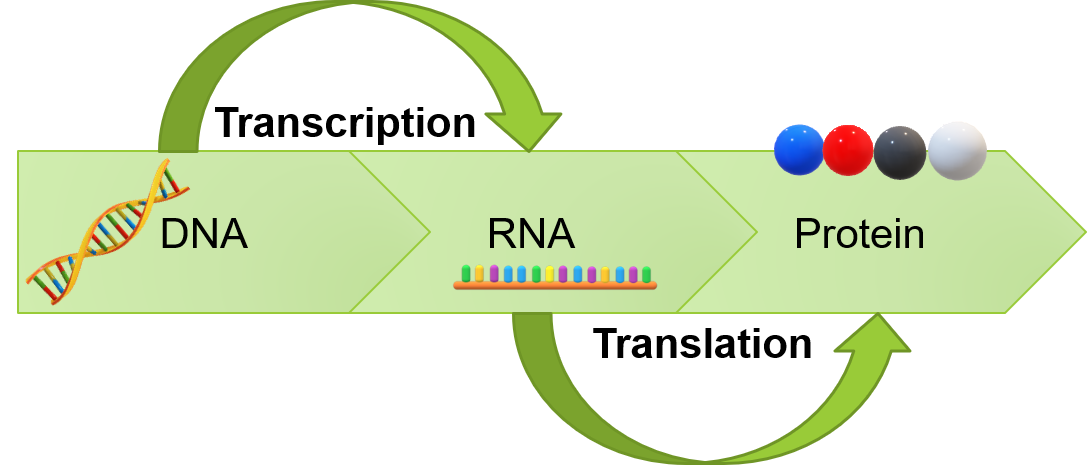

The nucleus or centre of a human cell contains the blueprints / instructions that make us, biologically at least, who we are. These instructions are encoded in our genes which in turn are made of sequences of molecules called DNA. DNA contain information for making specific proteins that ultimately express particular physical characteristics like brown eyes, for example. In order to sustain life, we must continually multiply and replicate our cells, which involves replicating our DNA in addition to using our DNA to create proteins and enzymes that are responsible for gene expression and our overall biological functioning.

The first part of that process of creating proteins is a step call transcription where a piece of DNA that codes for a specific gene is copied into something called 'messenger RNA' or 'mRNA' in the nucleus of the cell. The mRNA then carries that information out of the nucleus into the cytoplasm (the area within the cell surrounding the nucleus) where the information is translated into a protein. And then it's job is done!

The use of mRNA in therapies involves encoding the mRNA to make a protein that corresponds to the thing you want the immune system to respond to, for example Elliot's bowel cancer tumour. There are a number of challenges that researchers have had to overcome including making the mRNA capable of inducing billions of immune cells by making it more stable. In other words it had to create enough of an immune response to successfully deal with the tumours but not create too much of an immune response that causes other issues.

Precision and personalised medicine

The mRNA vaccine is an example of precision medicine as the vaccine is designed to work optimally on the specific patient's own tumour.

Personalised medicine, which encompasses precision medicine, is one example of a number of broad areas that are being investigated to slow down or even stop biological ageing. It is a topic we have written on previously👇🏾

The terms 'personalised medicine' and 'precision medicine' are often used interchangeably but they don't convey exactly the same thing.

Personalised medicine is a holistic approach to healthcare, a broad umbrella that includes other approaches that tailor treatment and preventative measures, of which precision medicine is one type. Precision medicine tends to encompass advanced technologies such as genetic testing, molecular profiling and big data analytics to classify individuals into more precise groups than just age and tailor treatments accordingly. You could say it is about getting the right treatment to the right patient at the right time. Personalised medicine recognises that patients are unique, they have different physical, biological and social circumstances and may respond differently to different treatment options.

How big is the market for personalised medicine? Estimates vary at approximately $500 - $650 billion globally, reaching almost $1 trillion in the next five years. Speaking at a conference last year, the CEO of Juvenescence, a company focused on treating and preventing the underlying causes of age-related diseases, highlighted that in 2022 investments being made into longevity reached $5.2 billion with much of that arguably in precision and personalised medicine.

Examples of personalised medicine

Personalised medicine can treat conditions in a targeted way, but can also help to prevent them by categorising patients in a more granular way. Here are some examples of personalised medicine:

Lifestyle and preventive medicine: Understanding an individual's genetic predispositions and the environmental factors that they are exposed to can enable that individual to avoid doing certain things or doing more of others. Food intolerance tests are good examples here where understanding what foods cause inflammation allow dietary changes to be made. I had one myself a few years ago that identified that rather than being lactose intolerant or sensitive (as my ethnic profile would suggest would be likely), it was actually the casein in milk that was causing my... er... symptoms. Unfortunately I had switched to 'Lacto-free' products which of course still contained casein. Genetic testing can identify genetic markers associated with increased risks for certain diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and allow for tailored preventive measures such as lifestyle modifications including specific exercise routines, regular screenings, and early interventions.

Pharmacogenomics: A key premise of personalised medicine is that people respond to medications in different ways. As I have already highlighted, most modern drug development goes through a series of tests or clinical trials to understand how well the drug works, the optimal dosage and what adverse side effects, if any, that there are. Findings from the trials are dependent on the make up of the trial participants. Historically, minority groups, older people and women have been underrepresented in clinical trials. Even putting that to one side, an individual's response can vary with height, weight and many other factors. Within the apparently same group of similar individuals, a drug may be toxic but beneficial, not toxic but beneficial, toxic and not beneficial or have no impact at all. Genetic tests can identify specific variations in a person's genes that may impact their response to certain medications. This information can help doctors select the most effective and safe treatments for individuals, determine the most appropriate drug dosage, minimising adverse reactions and optimising the effectiveness of the treatment.

Targeted therapies: We have already seen the potential with PDAC and bowel cancer, and there are other cancer treatments designed to target specific genetic mutations or molecular markers in tumours. Even at a more basic level, greater precision in chemotherapy dosing can reduce adverse side effects and improve the overall outcome.

Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food

Finally let's talk about diet.

The quote of this title is often attributed to the Greek physician and philosopher Hippocrates (albeit no one can actually find the quote in any of his writings!). It is not suggesting that food and medicine are the same thing but rather the importance of nutrition in building and maintaining a healthy life.

The Hippocratic oath which all doctors are invited to take on graduation contains an interesting line, literally translated as "I will apply dietetic and lifestyle measures to help the sick to my best ability and judgement; I will protect them from harm and injustice.”

There is much that can be achieved from a preventative and curative perspective from what we eat.

However, a problem with the diet industry, fuelled by the teeny-attention-span-binary-view driven by social media is that there is one diet that is the best for all. Keto, Paleo, Atkins, intermittent fasting, restricted window eating, Dukan, South Beach, plant-based, carnivore-based, dash, pescatarian, mediterranean and even the 'hard boiled egg' diet.

The same issue remains with added dimensions. Diet is very personal. Our bodies react to different foods in different ways (ok there are some commonalities clearly) but different foods will cause inflammation in some and no response in others. In addition diet will be dependent on what the individual is trying to achieve - weight loss or weight gain? muscle building or cardiovascular stamina? or both?

Bottom line, understanding where your starting point is will be key in working out the right personalised diet for you.

Conclusion

The notion of an 'average person' can be an inherently flawed concept unable to account for human complexity - we discussed that previously with regards to clinical trials and in this Sunday Brunch we have moved from the group to the individual to the potential of personalised and precision medicines.

It is potentially an important DEI theme.

Whilst much progress has been made, we are still at the early stages. Could these early mRNA trials, for example, herald a totally new way of 'doing medicine'? Maybe.

I shall leave you with this quote from nineteenth century Canadian physician William Osler:

'It is more important to know what sort of person has a disease than to know what sort of disease a person has.'

Please read: important legal stuff.