Sunday Brunch: our future forecasts don't need to be precise...

As an investor I would rather be roughly correct than precisely wrong. Or more strictly I would rather be broadly right about the two or three things that really matter to a company, even if it meant that I got everything else wrong.

"Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future". Attributed to Niels Bohr

As an investor I would rather be roughly correct than precisely wrong. Or more strictly I would rather be broadly right about the two or three things that really matter to a company, even if it meant that I got everything else wrong.

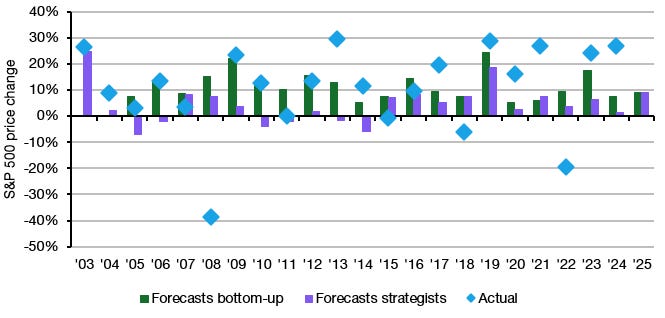

Investors, like most people, have an obsession with forecasting. And we generally do it very badly, but that doesn't seem to stop us doing it, over and over again. Often in incredible detail.

And yet what we often really need to know is not the exact market share (to two decimal places) of some new technology in 2028, but instead what is the direction of travel. And roughly how quickly things might change, so we know when the industry might reach a tipping point - when the transition becomes so established that the old technology and way of doing things is no longer relevant. And what markers might I use to check on progress.

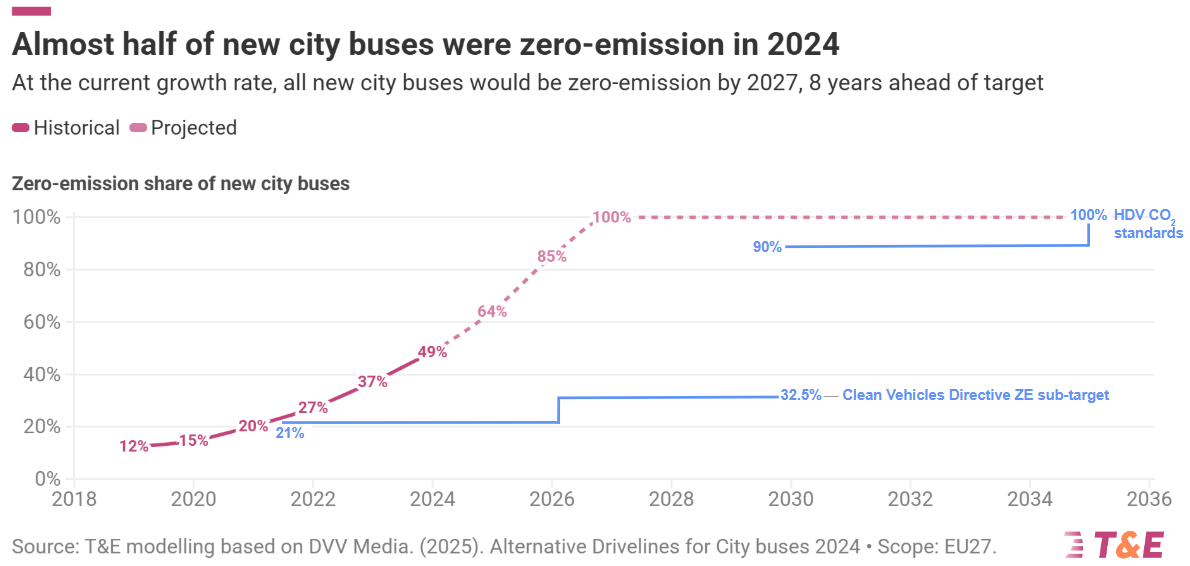

I was reminded of this when I read a recent blog from T&E on zero emission buses in Europe. It wasn't that long ago that these were a rarity, making up less than 1/10 of new sales. And many analysts expected them to remain at a low market share for many years. And yet, as of 2024 that number is now just a whisper below half (49%), with most of these being electric.

Are we at a tipping point in this transition? The blog suggests all new city buses could be electric by 2027. Which would be some 8 years ahead of target. This feels a little optimistic, with a decent number of countries reporting zero emission sales at below 1/3 of the total.

But it's probably fair to say that the trend is now pretty fixed. There may still be some new diesel buses sold in say 5 years time, but it's safe to bet it will be a small percentage. Making buses is not quite as much a scale exercise as making passenger cars, but it cannot be long before the economies of scale just don't work any more.

So, from an investor perspective we can make the assumption that any company that depends on selling diesel buses in Europe is probably living on borrowed time. And any argument about 'will market share be 85% or 95%' only adds a small amount to our knowledge.

How do long term investors think about investments?

Many people work on the basis that the more you know about a company, the better placed you will be to make a good investment decision. And they think that this extra information allows you to model the company financials in greater detail - giving you a more precise valuation.

But this is not really correct. It's far more important to understand the two or three key issues, how the company is reacting to and/or preparing for them, what is the rough probability of key events occurring, and what it might mean for valuation.

What issues might be seen as key? For a consumer goods company, it might be how they are preparing for the trend toward healthier food, or how they are working to make their supply chains more resilient. For an automotive OEM it might be about the transition period as they move to more EV's (including the impact on their brand values), or how they will adapt to the new supply chains this will require.

And yet, when companies hold capital market days, they often have slide after slide that digs into the detail. These events are a great opportunity to say to investors - this is what really matters. It's the big picture that will drive value, so let's not get too caught up in the detail.

And how does the big picture help with valuation ?

Regular readers should know by now that a company's share price is driven by the market expectations of its future cash flows. Given this you might think that knowing more about a companies operations allows you to have a more precise cash flow estimate. Leaving aside the challenge of knowing the future in detail, it's also useful to understand how many analysts use their forecasts to estimate financial value.

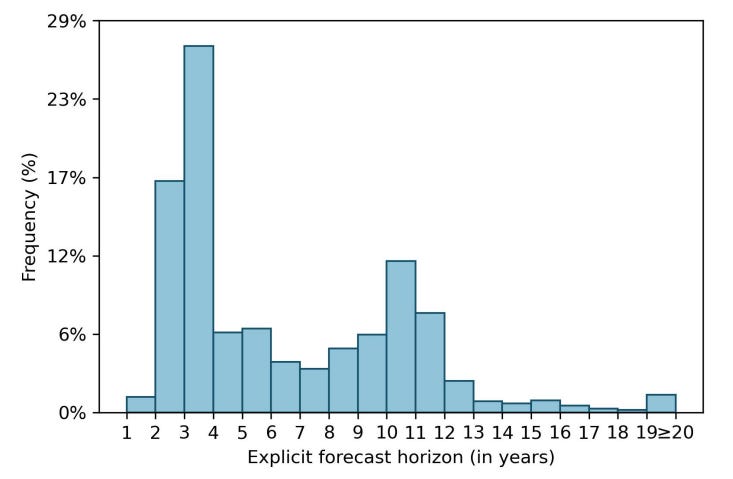

Joachim Klement, it was his blog I quoted above, recently wrote about some research from Decaire & Graham. They identified that "typically an analyst will explicitly model cash flow growth for the next 3 to 4 years, and then assume that growth will revert to some steady long term average". This long term steady growth period makes up what we call the 'terminal value'. Mathematically this frequently makes up about 75% of an analysts share price estimate/target.

So lots of (false?) precision for the next few years and then a very broad assumption about the future. I don't know about you, but I don't know many industries where a company steadily plods along for a very long time at a low rate of cash flow growth. What seems more likely is that once they hit the low growth period, they fade away to nothing. Often replaced by something better.

And in many cases companies can sustain good growth for more than 3-4 years, this is called beating the fade.

A good understanding of the big drivers of value can help us better 'model' a companies likely future cash flows. Is this a company that is likely to fade away quickly? Or will it beat the fade and deliver 'sustainable' growth for many years or even decades?

So, as investors, let's focus on a few key issues. And leave the small details to others. And maybe, just maybe, companies should do the same. Using their capital markets days, and other similar communications, to better educate investors on what really matters.

Life is what happens to you while you're busy making other plans

Some of you may have noticed that I have published a bit less over the last couple of months. To misquote John Lennon, life happened and it was messy. As a result I am taking a bit of time out, and so I will be publishing a bit less through March and into April. All going well, I will be back to full steam ahead by later in our spring.

One last thought

Sometimes the foundation for a firm's success or failure is based on what it invested in over the last 3 to 5 years (or even longer). This is especially true when we consider innovation. We all know that companies should not plan for what they see now. They need to invest for what the future customer will want and be willing to pay for. And if this doesn't happen they can falter from being market leading to the middle of the pack. Or even worse.

Please read: important legal stuff.