Sunday Brunch: more on getting financial people to listen

Back at the end of May I wrote the first blog in a series on the topic of what gets financial peoples attention when we talk about Sustainable Finance. And yes, its mostly, but not exclusively, about money. My starting point is that we all want to deliver change and impact. Which means that we need to be able to persuade companies that sustainability can also add financial value.

In that first blog I discussed the motivations of generating profit now, the potential for future profit, and managing technological pressure. Today I want to round out the list by discussing the motivation to act in relation to regulation/social pressure, and how we get the right mix of carrot and stick. By this I don't mean ESG regulation and reporting. This is about regulation that directly impacts a companies operations, and hence their profit and loss - you must use these buildings materials, your cars must not emit more than X CO2/km, you must stop using gas boilers and you must reduce fertiliser usage by X%. The focus here is on Europe, which is the engagement region I know best.

Just to quickly recap - my professional life has largely been spent persuading financial people to listen: as a corporate finance adviser and banker, as a broker to investment funds, and as an investor: persuading companies to listen and act. I now want to bring the lessons I learnt from this into sustainability finance.

If you want to read the rest and are not already a member...

Regulation and social pressure

When most sustainability and ESG people talk about regulation, they often mean ESG reporting regulations such as the recent update to the European Union Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD).

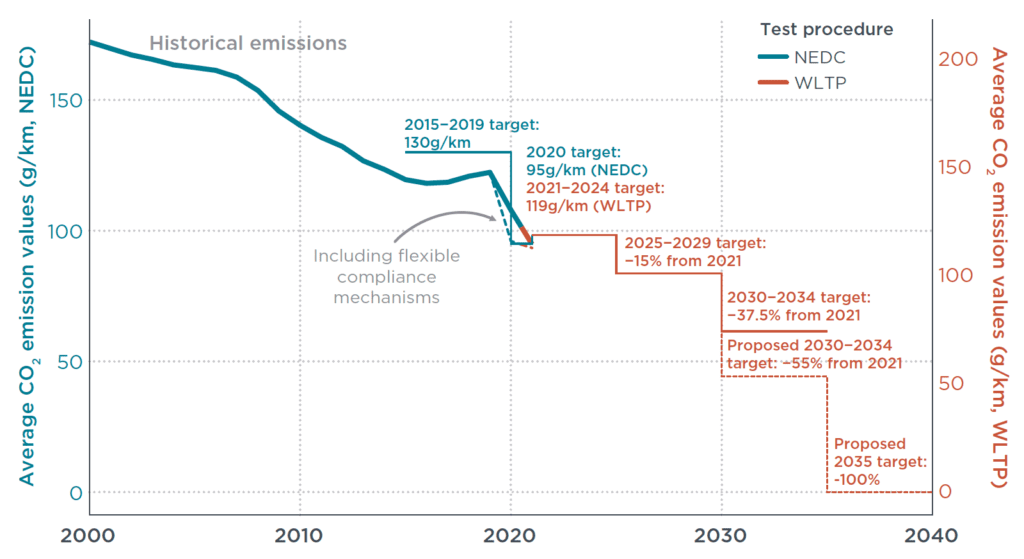

While these are important, most finance people are more concerned about regulations that have a direct financial impact on their business. A good example of this second type of regulation is Regulation (EU) 2019/631 - which covers the CO2 emissions of road transport vehicles sold in Europe. Non-compliance brings real costs, this is not just about reporting.

From a finance perspective, how do these different types of regulations differ?

To be clear, this doesn't mean I don't see the advantages of the various sustainability reporting frameworks. I can see the benefits of investors and other stakeholders having more information. I am a particular fan of the EU taxonomy, which is a useful classification system for economic activities that can be considered to be environmentally sustainable. Although even here, politics plays a part, with the European Parliament backing the labelling of nuclear and gas as green.

My concern is that the various reporting requirements put the onus on investors and other stakeholders to act. Without that action, the reporting standards just end up giving us useful information. In a few years everyone should have access to much of the data to make the required investment judgements. But it's what happens next that bothers me. It's not clear that most investors have the resources, the expertise, or the time, to run the required detailed corporate engagement programmes. By comparison direct rule based regulation, with suitable fines, can drive action more directly.

Regulation as a reporting requirement

Under the CSRD from the 2024 financial year, many companies need to start publishing information related to environmental matters, social matters and the treatment of employees, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery and diversity of company boards. The logic underlying the process is to ensure that ...

investors and other stakeholders have access to the information they need to assess investment risks arising from climate change and other sustainability issues. They will also create a culture of transparency about the impact of companies on people and the environment.

Putting it another way, it's underpinned by a belief that if you measure something, then it gets managed. This is often linked to the work of influential business strategist's such as Peter Drucker. Although apparently he never said "what gets measured gets managed”. In fact he argued the opposite, that many of the things that are important to a company cannot be measured - but that's a debate for another day.

From the perspective of the company, they are 'just' obligated to report the information. There is no legal obligation to act, to change their business practices. There is however an implicit assumption that stakeholders and the 'court of public opinion' will, over time, put pressure on the company to improve its practices.

Regulation with financial implications

By contrast, regulation (EU) 2019/631 sets very concrete fleet wide targets for CO2/km emissions for different types of new road transport vehicles. The level to be achieved by 2024 is a very specific number - 95g CO2/km. And any company that fails to meet the standards is required to pay an excess emission premium of €95 per car per g/km of target exceedance.

The incentive to meet the standards is clear - go over the target and there is a financial cost. Perhaps unsurprisingly, almost all car manufacturers — either individually, or as members of a pool — met their 2020 targets. This direct approach seems to be working.

A slightly weaker example is the recent German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act, which requires that German companies "make reasonable efforts to ensure that there are no violations of human rights in their own business operations and in their supply chains". This can be thought of as a best endeavours act - the companies covered must make reasonable efforts, at their own discretion. This gives companies the companies a bit of a let out. But, the bottom line is that there are fines and other sanctions for companies that fail to meet their obligations.

And something else to watch, trade unions and non-governmental organisations may be authorised by an interested party to conduct litigation. In my view this is going to be a very interesting trend over the coming decade, with many organisation's gaining practical expertise in using the law to force change on reluctant companies. Certain NGO's seem to be increasingly well resourced in this area.

Round up - what does this mean for Sustainable Finance?

First, we suggest that a greater focus is placed on lobbying for rule based regulation, such as regulation (EU) 2019/631 on vehicle emissions. In the right situation, this type of regulation can be very powerful as a mechanism for change. There are many other similar avenues, such as building codes (which can require the use of certain materials, limitations of demolition, and stronger insulation targets).

Second, if we are going to make the reporting requirement type of regulation the bedrock of our approach to sustainability, then investors need to put a lot more resource and expertise into informed engagement. This covers everything from understanding what changes we want the companies to make, what implications this has for their financial value creation, and how this will work in terms of company culture. Change is hard, and companies are going to need a lot of support if they are going to make it happen.

Thirdly, and more positively. We need to broaden the discussion about how companies acting with purpose also create financial value. It's something that Alex Edmans (of Grow the Pie fame) and Rebecca Henderson (author of Reimaging Capitalism in a World on Fire) have been researching and speaking on for a while now. More of us need to listen.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.