Sunday Brunch: it's a question of character(istics)

The world of investing and sustainability can challenge our traditional ways of looking at the world and characterising and grouping things.

When my children were younger we were fortunate to live in the countryside. Our back garden was a mixture of traditional and 'the wild' - the latter a function of us living in a wooded area in Kent that was devastated by the October 1987 hurricane that took some by surprise.

One significant responsibility I had was preparing for the Easter Sunday 'egg hunt' which actually involved hiding (but still discoverable) chocolates of various shapes, sizes and tastes around the garden.

I remember fondly how, once found, the kids would sort their spoils by size so that each of them had broadly the same volume of chocolate. However, sometimes they would sort by wrapper colour and sometimes by animal/character shape - the equality characterised in a different way.

We have historically grouped things in certain ways. At school we are used to playing sports according to the year group that we are in. As someone with a June birthday (and hence young in my year) this was often a detriment. But it doesn't have to be that way. We could select based along a different characteristic to age. They do just that in Australia moving players between age groups based on height and weight factors which creates inclusion and may allow for the development of skills without the fear of getting trampled (pun intended) by purely size during those early years.

The world of investing and sustainability can challenge our traditional ways of looking at the world and characterising and grouping things.

Let's look at that...

If you are not yet a member, to read this and all of our blogs in full...

The X-Factor

One of my roles at Morgan Stanley was in a team called Systematic Advisory Services. My team's aim was to 'better monetise the firm's quantitative assets in helping a broader range of our clients'. That involved providing quantitative hedge funds with a broader sales service and helping them understand how the fundamental world thought about things; and helping fundamental investors understand the world of quant, data and factors.

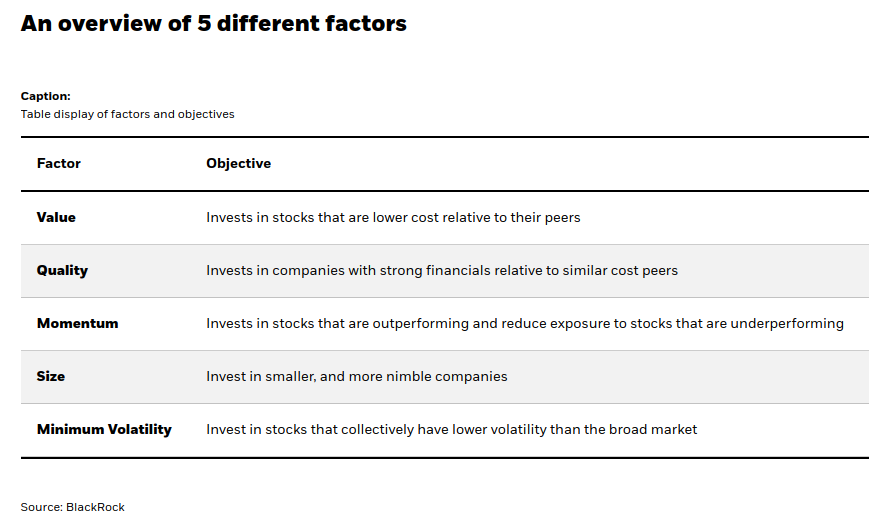

Factors. The mythical data science-y things that drove complex models to outwit mere mortal investors. What are they?

They are just chocolates organised by colour rather than size, rugby players organised by size and weight rather than just age. They are just a different way of characterising stocks.

In fact traditional, fundamental investors have always used factor investing, it's just that those factors were 'geography' or 'industry' rather than 'value' or 'growth'. Factor investing postulates that all stocks sharing certain characteristics will move in the same way.

You may choose to invest in Taiwanese (geography) Tech (industry) stocks because you think that sector will benefit from increased demand for memory chips (of course there may be some differences between companies, but the overall group will benefit).

You may alternatively think that the market environment is good for those stocks that are already outperforming or have good momentum, regardless of what geography or industry they are in.

Different market environments support different strategies and different ways of grouping or characterising.

We have been through an unprecedented period of liquidity following the quantitative easing that started post the global financial crisis. This has meant that stocks have been able to perform on sentiment even if some of the more traditional accounting metrics are not being met, such as profitability.

With an increasing focus on sustainability more generally, could fundamental measures become more important?

In any case are the old ways of grouping appropriate in truly identifying impacts in sustainability themes?

Sustainability Factors - do we need to change our viewpoint?

There are a number of examples where traditional ways of characterising may not work.

We previously discussed the work of Edmans, Flammer and Glossner on DEI. You can read our thoughts here (in full with a Premium and Professional membership) 👇🏾

and here (in full with a Professional membership) 👇🏾

I used the example of my mate Iain. Iain is 'white English' according to the UK census. I am 'Asian British/Indian'. We are demographically diverse. However, we have known each other since we were three years old, we have had multiple shared experiences, got into trouble in similar ways, eaten the same dodgy kebabs and have a similar outlook on life. We are also both follically-challenged up top but that may not be relevant to this discussion. Iain is very fit, an almost elite runner, triathlete and long-distance swimmer. Currently that is a big area of diversity between us.

So there could be a problem in identifying diversity to begin with using traditional demographic methods. From that starting point, it could be that corporates and organisations are then approaching DEI in the wrong way.

Rather than focus on those traditional classifications, Edmans, Flammer and Glossner looked for the outcomes. They looked at proprietary data from the Trust IndexTM which is an extensive employee survey that forms the basis of the '100 Best Companies to Work For in America' list. They identified questions that they felt encompassed DEI, aggregated the responses from those questions to produce a "grass-roots" or bottoms up measure of actual DEI. Forget policy statements, how are actual values being lived out? i.e. what is the DEI culture?

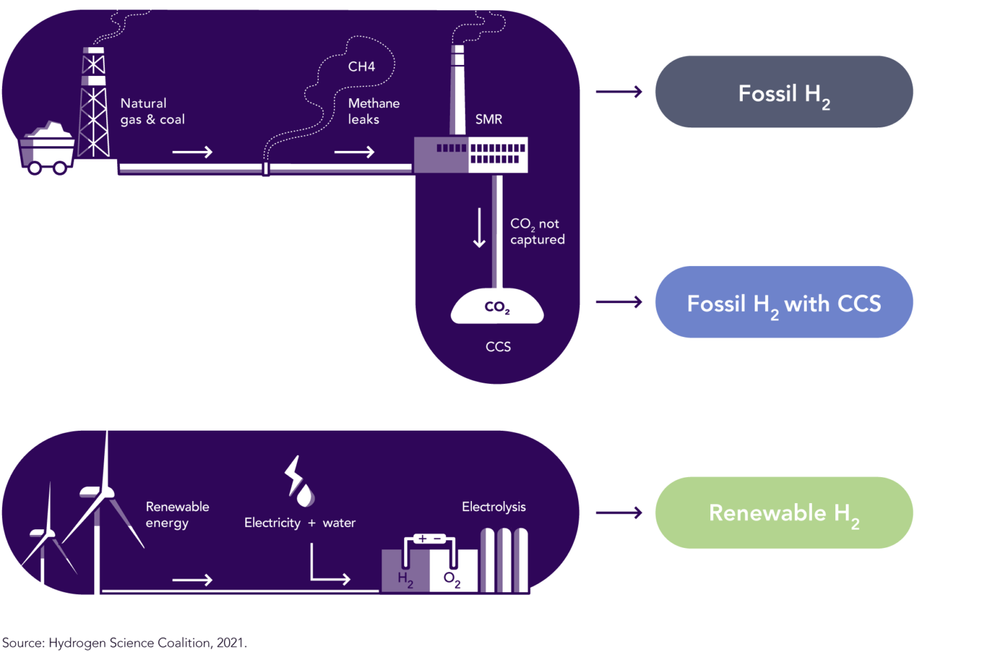

Another area is energy. Traditionally, and even in more recent times, focus has been on the source of energy or power generation. The starting point is the 'oil and gas industry' or the 'nuclear industry' or the 'wind industry' etc.

Consider the use of the term “the hydrogen economy”. In my opinion, this is problematic as it leads us to the starting point that we have this commodity hydrogen, and we need to find something to do with it. As Professor Maslow (1966, “The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance”) put it “If the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail.”

Whilst the Hydrogen Science Coalition believe that "innovative solutions like hydrogen are an important piece of the puzzle" to decarbonise the global economy, they have a view on where it should be used. They believe that renewable hydrogen should deployed for "hard to decarbonise sectors, starting with where fossil hydrogen is used today."

Hydrogen is needed as a feedstock in a number of crucial processes most notably the Haber-Bosch process in manufacturing ammonia, a key component in fertilisers.

It is a piece of the puzzle, but not the puzzle itself.

Instead of thinking about the 'input' let's focus on the outcome with a more holistic approach. Rather than what fuel should I use to heat my home, ask the question 'how do I keep my home at an appropriate temperature?' Even further, what is it that I actually need? is it heat? is it pressure? is it a raw material itself? Horses for courses. This is something we shall explore in an upcoming Deep Dive.

Where's my science?!

I'll finish with an interesting debate I came across on LinkedIn about a draft 2024 high school curriculum for New Zealand, specifically how science will be taught. The proposal is for science to be taught through contexts: The Earth system, biodiversity, food, energy and water and infectious diseases. The initial reactions were of outrage of a 'dumbing down' of education and that the new curriculum was heavy on philosophy and light on actual science etc. Where's the physics and chemistry?!

I'll swerve that debate for the moment. Actually it comes down to execution. Indeed one of the new curriculum writers commented that key areas of physics and chemistry would be taught but that they "will be teaching the chemistry and physics that you need to engage with the big issues of our time."

Contextual learning is important. It can bring a subject to life and increase engagement. It can also make it more applicable in the real world.

I studied physics and chemistry to the highest level in school (I did both A'Levels and S'Levels which are a level above) and I found so much overlap that at times the distinction was arbitrary. Here are the Cambridge dictionary definitions:

Physics is the scientific study of natural forces, such as energy, heat, light, etc.

Chemistry is the scientific study of substances and how they change when they combine.

Biology is the study of living things.

Arguably understanding about energy is relevant to all. Think about something like Brownian motion. I can find relevance across all three sciences. Think about antimicrobial resistance. It is biology (living organisms), it is chemistry (how substances combine to form antibiotics etc) and physics (formation of biofilms and how they might be disrupted with physical structures).

As we transition to a more sustainable way of living, so too must our way of characterising and grouping. Our viewpoint needs to change.

It can't be 'same as it ever was'.

Note 1: Quantitative factor investing is, of course, more complex in practice than I have made it sound.

Note 2: It ALWAYS rained when I was out prepping the 'egg hunt' but never when the kids went out to search. Thanks very much Michael Fish.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.