Sunday Brunch: healthcare, underrepresentation and the flaw of averages

Increasing diversity in clinical trials is one of the foundations of health equity

In 1950, the U.S. Air Force took physical measurements from 4,000 pilots across 140 dimensions and took the averages of those measurements to design the 'perfect cockpit'. This robust data-driven approach however did not translate well into flight missions. Once the new cockpits were introduced, previously capable pilots were suffering uncontrolled crashes. So what was going on?

A young analyst, Lt. Gilbert S. Daniels, found that not a single pilot fitted within the middle 30% range across 10 key dimensions. This insight led the Air Force to abandon the average as the design standard. Instead, they adopted a new principle of 'individual fit' by making cockpit components adjustable to accommodate diverse pilot sizes. The notion of an 'average person' was discarded as an inherently flawed concept unable to account for human complexity. The 'flaw of averages.'

And yet that very principle has been central to clinical drug trials for decades.

Look at the efficacy and side-effects for an 'average group' in a trial and apply that to the broader population. In recent years the concept of personalised and precision medicine has come to the fore. That is something for another blog. In today's Sunday Brunch I'll focus on the composition of clinical trials.

Historically, that 'average group' has been far from it.

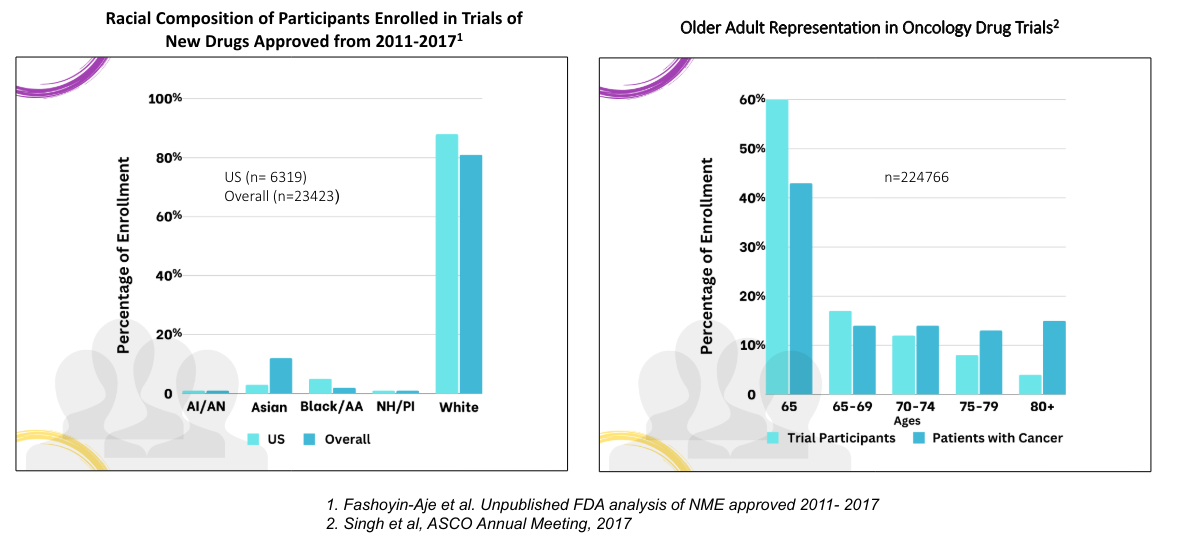

For example, older Black and Hispanic Americans are twice and 1.5 times as likely, respectively, to have Alzheimer’s than their white counterparts, but the majority of clinical trials have historically featured white patients.

Sex differences are important too. Until the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993, a 1977 FDA guideline banned most women with 'childbearing potential' from clinical trials.

The FDA has noted previously that minorities, the elderly and women have historically been underrepresented in clinical trials. Separately, analysis has shown that a 'standard drug dose' typically leads to higher blood concentrations and longer drug elimination times in women contributing to more frequent adverse drug reactions in women.

That has improved greatly with an FDA drug trials snapshot (2015-2019) showing that male and female participation has become more balanced. However, on a global basis, 76% were described as 'white', with only 7% as 'Black or African American' - the US 2021 census showed more than 12% of the US population were 'non-Hispanic black'.

Back in April 2022, the FDA issued draft guidance 'Diversity Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants From Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Populations in Clinical Trials'.

After two years of comments, the FDA is late in issuing final guidance on how and when drug and device companies should submit diveristy action plans for clinical trial research with the document still under review at The White House.

Understanding the particular needs of communities and their involvement in drug trial and discovery is an important part of actually providing access - an important part of health equity.

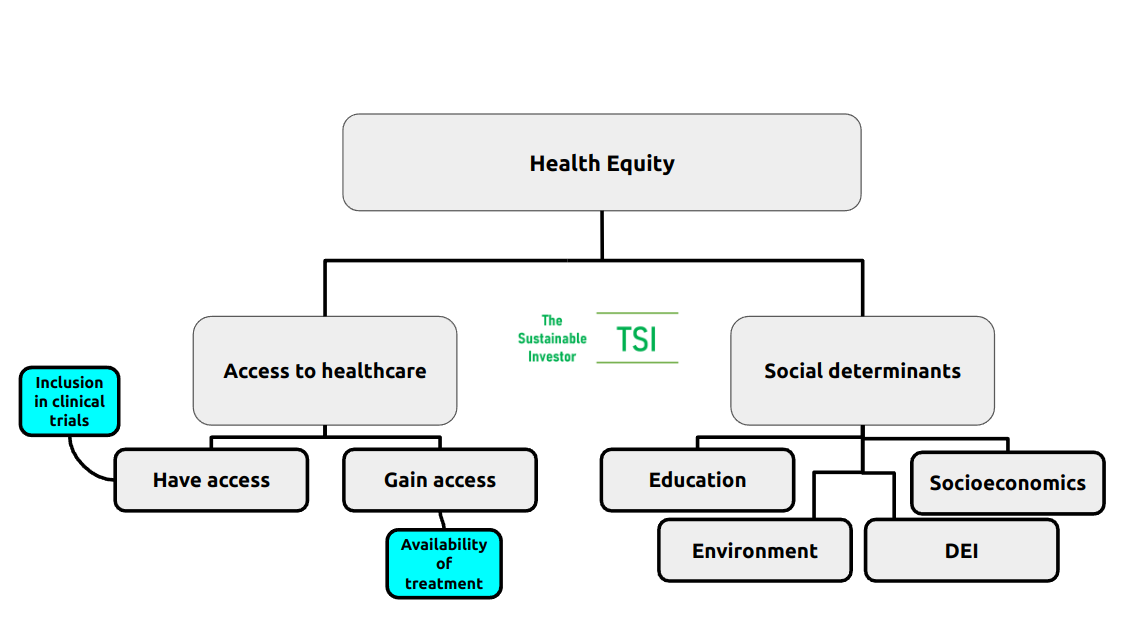

Before we look a little closer at what is being proposed by the new FDA rules, let's start off with defining what health equity actually is.

If you want to read the rest and are not already a member...

What do we mean by 'Health Equity'?

The World Health Organisation describes health equity as being achieved when "everyone can attain their full potential for health and well-being."

It is quite a broad definition. Let's look at it the other way around. What are the factors that can prevent people achieving their full potential for health and well-being? What are the differences between different people? What are the disparities?

Here is what US Congress had to say about it in the 'Health Equity and Accountability Act of 2022': Health disparities are a function of not only access to health care, but also the social determinants of health that directly and indirectly affect the health, health care, and wellness of individuals and communities, including:

- the environment

- the physical structure of communities

- nutrition and food options

- educational attainment

- employment, socioeconomic status

- race, ethnicity

- sex, gender identity

- geography

- language preference

- immigrant or citizenship status

- sexual orientation

- disability status

Taking all of the above into consideration, we arrive at the following overview:

A 2022 actuarial study by Deloitte concluded that health inequity in the US accounted for roughly US$320 billion in annual healthcare spending potentially ballooning to more than US$1 trillion by 2040 if that inequity was not addressed.

As well as the obvious direct link to UN SDG goal 3, health equity can support and be supported by the other UN SDGs too. The social determinants of health, as mentioned previously, are clear across goals 1-11. Goal 11 itself, "sustainable cities and communities" is particularly pertinent in bringing many social determinants together.

With health equity come broader benefits to society as a whole. Life expectancy rises and importantly productive life expectancy rises. That brings with it greater income levels, improvements in the local economy, education and attainment. You can read more about that here👇🏾

You will have noticed that under 'Access to healthcare' I have separated out 'Have access' and 'Gain access' - the latter is more about delivery of health services including medication and procedures, whilst the former is really about services existing for any given community or demographic. That starts with understanding the particular needs of communities and their involvement in drug trial and discovery.

Another aspect in pushing back on the 'flaw of averages' is the concept of personalised and precision medicine. This is something for another blog, but you can read more about it here👇🏾

In today's Sunday Brunch I'm going to focus on clinical trials.

The charts below from the FDA shows the historically skewed nature of clinical trials in oncology, for example.

So what is being done to improve the inclusivity in drug and treatment trials?

What is being done to help?

There are a number of initiatives already in play aiming to address underrepresentation of key cohorts, particularly those that are especially vulnerable to particular conditions. This takes a couple of forms that are very similar but different.

Firstly, undertaking trials for conditions that are much more common in certain communities. That may include some rare conditions but can also include conditions that impact thousands or even hundreds of thousands of people.

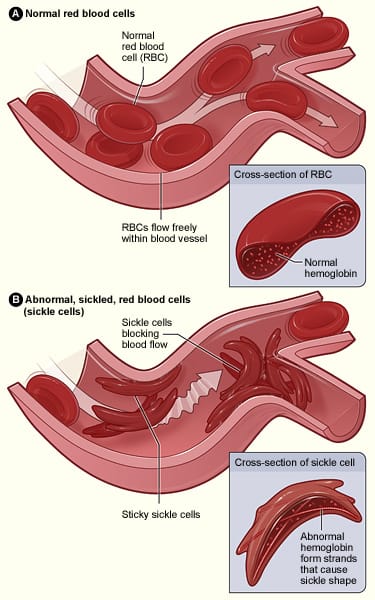

The FDA approved the first gene therapies for treating - and potentially curing - sickle cell disease (SCD), Casgevy (from Vertex Pharmaceuticals) and Lyfgenia (from Bluebird Bio) in December 2023. SCD is an inherited condition that makes red blood cells hard, sticky and 'sickle-shaped' (hence the name). Sickle cells die quickly and so there is a constant shortage of red blood cells plus arteries can get clogged by them too restricting blood flow and increasing stroke risk, for example.

About 5% of the world's population carries trait genes for blood haemoglobin disorders - the main one being SCD. In the US the condition affects more than 100,000 people and 20 million people worldwide, but SCD is much more common in certain ethnic groups, particularly those of African descent.

Secondly, addressing the balance of participants in clinical trials. Historically eligibility criteria, which are essential in trials, have sometimes inadvertently screened out suitable participants and so trial design is key.

But the inclusive strategy can begin before a trial drug even enters the clinic.

Outreach Pro launched by the National Institute on Aging is a tool designed to increase awareness and interest in Alzheimer's and other dementias among non-white populations. The tool can be tailored to local populations too.

And back in 2021, Genentech announced the creation of a coalition of clinical research sites located in areas with higher Black and Hispanic populations with the aim of increasing their participation in cancer studies.

So what is the FDA proposing with its new guidelines?

The FDA guidance

The Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act (FDORA) was signed into law by President Biden as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023. This law includes the provisions for clinical trial diversity and modernisation. One of the requirements is for sponsors of certain clinical studies (phase 3 or other pivotal studies) to submit Diversity Action Plans (DAPs) to the FDA. Essentially it is this that gives the authority to the FDA to require that DAPs specify the enrollment goals disaggregated by race, ethinicity, sex and age group and, importantly, provide the rationale for those goals. They should also state how they will reach those goals - enroll and retain participants from the relevant population.

The first DAPs need to be submitted for studies where enrollment begins 180 days after publication of the final guidance. So at the earliest that is the begining of December 2024.

The expected contents in the draft guidance can be found in section VI here https://www.fda.gov/media/157635/download

In producing the guidance, feedback was received from various clinical and community groups and through the comment process it is hoped that there will also be teeth to ensure compliance. Currently the recommendations are non-binding.

Conclusion

Health equity brings broader benefits to society as a whole. Life expectancy rises and importantly productive life expectancy rises. That brings with it greater income levels, improvements in the local economy, education and attainment. For all.

Gaining access to appropriate healthcare so that one can "attain their full potential for health and well-being" is more than being able to be given available treatments affordably. It also about those treatments being created and being effective in the first place.

That starts with discovery and ultimately trials that ensure that efficacy and side effects are considered for all groups of people.

There isn't a one size fits all and the flaw of averaging is especially compounded when whole groups of people aren't even in the sample!

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.