Sunday Brunch: diabetes, fertiliser and Jurassic Park

When resources are scarce we may need to prioritise their use. So even if we can, maybe we shouldn't.

In the 1993 film Jurassic Park, chaos theory expert Dr Ian Malcolm (played by Jeff Goldblum) launches into a tirade against the park owner, John Hammond (played by the late Richard Attenborough) ending with this iconic line:

"... your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn't stop to think if they should."

Subsequent films in the Jurassic Park series would tend to support the concerns of Dr. Malcolm. Bring dinosaurs back to life? People died. Mix up the DNA of dinosaurs to create new more terrifying dinosaurs? People died. There are sometimes generally accepted 'moral absolutes' - you know what, we just shouldn't really do that.

But things can also be a bit more nuanced. As well as new technology being developed to help us live more sustainably, existing technology could also be adapted for new uses. However even if we can apply a technology or solution to multiple uses, we may need to prioritise as resources may be scarce. And that prioritisation can result in a use case not being addressed by that solution.

Hydrogen is a good example of that, but let's start by looking at an example in the healthcare space, how the drug semaglutide, developed to treat type 2 diabetes, has recently been adapted and heralded as a weight loss drug and in the process created a global shortage.

If you are not a member yet, to read this and all of our blogs in full...

Diabetes, weight management and semaglutide

When the food you eat is digested into glucose and enters your bloodstream (called 'blood sugar'), a hormone called insulin, which is produced in your pancreas, moves that glucose out of the blood and into cells, where it's broken down to produce energy.

However, if you have diabetes, your body is unable to break down glucose into energy, because there's either not enough insulin to move the glucose, or the insulin produced doesn't work properly.

There are two main types of diabetes:

- Type 1: the pancreas doesn't make any insulin because your immune system attacks the cells in the pancreas that would normally make it.

- Type 2: the pancreas makes less insulin than normal and you become resistant to it. i.e. you have insulin, but you stop being able to use it.

A study published in June 2023 in The Lancet estimates that 529 million people worldwide had diabetes in 2021 resulting in healthcare expenditures of approximately US$966 billion in that year.

I'll focus on type 2 which accounted for 96% of all diabetes cases globally in 2021.

The condition can be managed through eating an appropriate diet, exercising, insulin and other medications - the most common one, metformin, improves how the body responds to insulin and has been used for 30+ years.

Since gaining FDA approval in 2017, there has been a new kid on the block: semaglutide. Developed by researchers at Novo Nordisk and sold under the brand name Ozempic (as an injection), it has also been used to treat type 2 diabetes. It mimics a naturally occurring hormone (GLP-1) that stimulates the secretion of insulin, as well as a number of other things including lowering appetite.

On that last point, researchers discovered that in larger quantities (more than double the maintenance levels for diabetes treatment) it can actually act as an appetite suppressor and, in conjunction with diet and exercise, can be used for long-term weight management. In June 2021, the FDA approved semaglutide injections for chronic weight management in adults with obesity or overweight with at least one co-morbidity (i.e. something else potentially life threatening) - sold under the brand name Wegovy.

The global average levels of obesity are 21.8% of a country's population. A UK government health survey estimated that almost 26% of adults in England are obese compared with the European average of 23%. Other countries obesity rates according to Wisevoter are around 38% in the US, 7.4% in China and 4.6% in India.

Obesity is one side of malnutrition and normally defined as excessive fat accumulation presenting a risk to health. A Body Mass Index (BMI) of more than 30 is considered obese. Measurement of obesity is problematic as traditional measures such as BMI are too simplistic, but other measures including fat measurement or simple waist-to-height ratio are also used.

The WHO estimates that more people are obese than underweight in every region except sub-Saharan Africa and Asia. Significantly the problem is on the rise in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in towns and cities. This can be exacerbated as these countries may not have the same access to healthcare.

So if we now can use semaglutide to reduce obesity then we should right?

Well... there's a problem.

Semaglutide / Ozempic is in short supply as those with the means are buying up the drug as a quick fix to weight loss in general (not necessarily when obese), leaving type 2 diabetes sufferers short. Now there is a nuance of course.

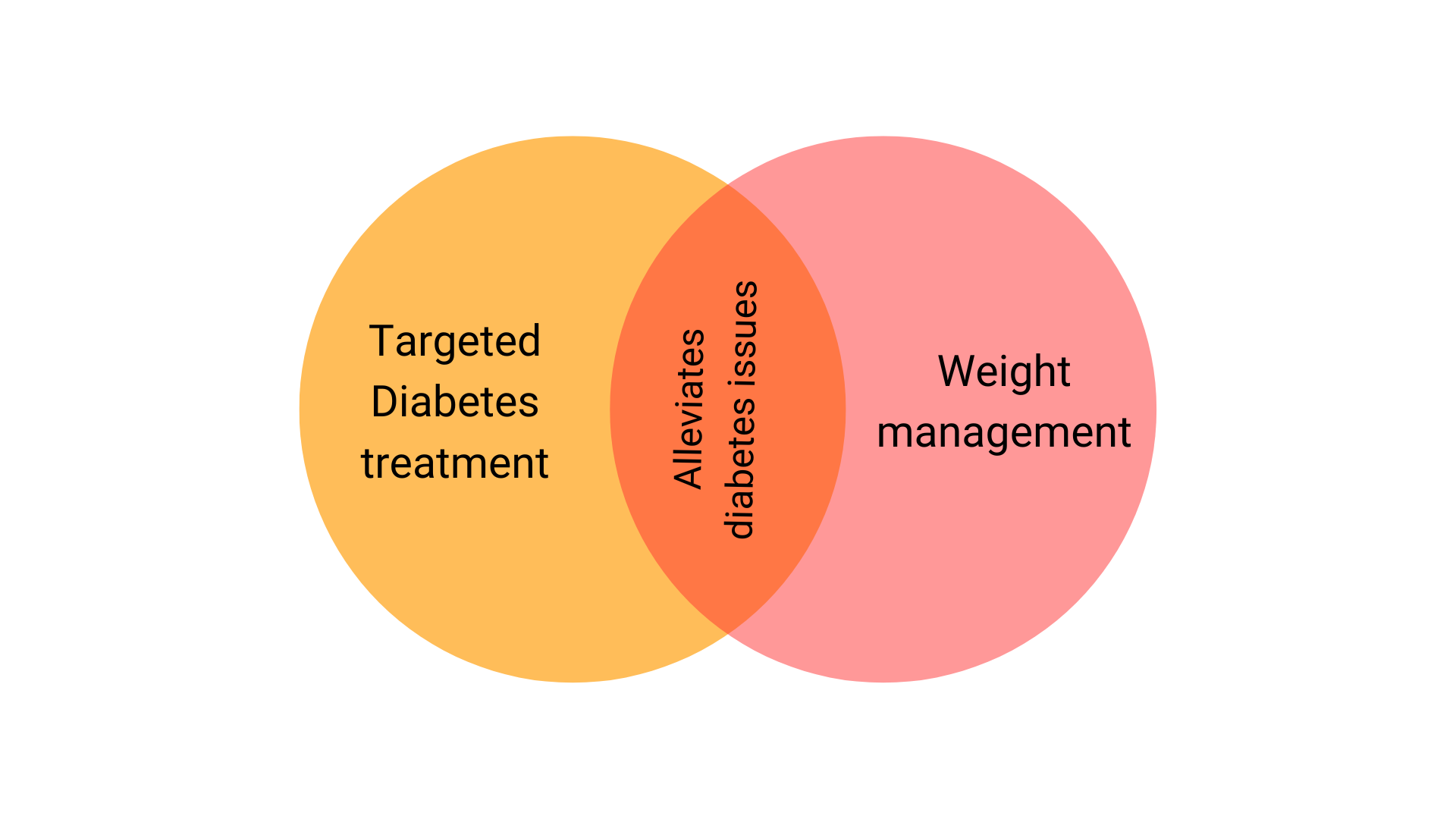

Obesity is widely recognised as a major risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes as excess body fat, particularly around the abdominal area, can lead to insulin resistance. And there are significant health risks with being obese in addition to diabetes: Cardiovascular disease, cancer, dementia, psychological distress and infertility.

So the nuance here is that in treating obesity more generally we will also be contributing to the treatment of diabetes - and other important ailments.

Bottom line though, deliverable semaglutide is scarce or at least not available for every possible use all at once and so prioritisation on medical grounds and most likely predominately to type 2 sufferers should be necessary.

Fertiliser, transport and hydrogen

Hydrogen is an important element that is used by humanity for a number of things critical for sustaining our way of life. You often hear about the 'hydrogen economy' as an important pillar for the sustainability transitions. We have written before about our concerns about that terminology - it's starting point is the supply-side! You can read that here 👇🏾

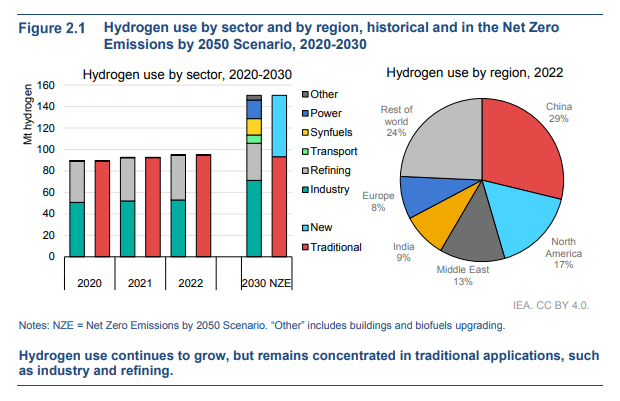

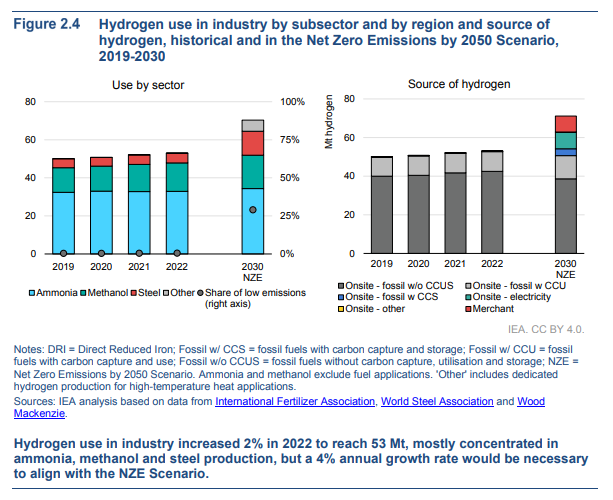

But let's focus on what we need hydrogen for - the demand side. The chart below shows hydrogen demand by sector (and region, but I want to focus on sector, i.e. use cases).

You can see that in 2022 demand was broadly split into two sectors. Of the just over 94 Mt of hydrogen used, refining (the grey bar) accounted for just over 43% and industrial uses (the green bar) roughly 56%. Transportation accounted for 0.04% so immaterial.

This next chart shows which industrial products use the most hydrogen.

You can see from the chart above that the industrial product that uses the most hydrogen is ammonia (the light blue bar at well over half). The majority of ammonia (around 80%) is used to make nitrogen fertilisers which are important in helping to ensure high crop yields and aiding food security.

However, almost all of the hydrogen used in both refining and in industry is made from fossil fuels.

Ammonia production has a direct CO2e footprint as big as Brazil's! So it is a clear priority for greening. We discussed that in more detail here 👇🏾

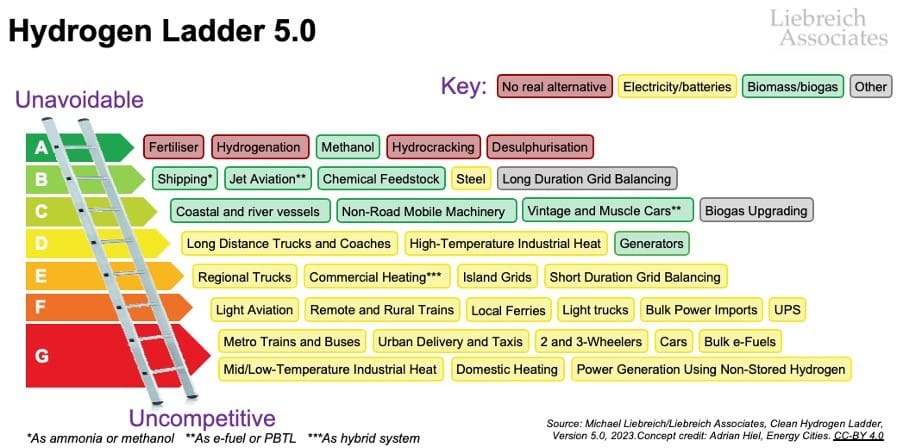

As Michael Liebreich so eloquently expresses in his Clean Hydrogen ladder, now on version 5, some uses of hydrogen make sense, but for many applications, we have better (electrification) alternatives.

The brown uses, where there is no real alternative, typically where hydrogen is an 'ingredient' in a process, is where any production of green hydrogen should be prioritised.

Can hydrogen be used for transportation and heating? Technically yes it can. Is it the most efficient? In the majority of cases it isn't.

A further complication in the decision-making process is that of cost reduction. Green hydrogen is likely to not see the cost reductions that we have seen in, for example solar through learning curve in electrolyser design and use. The issue with producing green hydrogen is that a big chunk of the costs are not electrolysers but site construction and pipes and pumps which have not changed for decades. This is something we shall discuss in a future members' blog.

Bottom line, deliverable green hydrogen will be scarce or at least not available for every possible use and so prioritisation will be necessary.

So we live in a world where resources are scarce.

So when it comes to prioritising, in the same way that semaglutide should be prioritised for sufferers of type 2 diabetes (over weight loss), so should green hydrogen production be prioritised for those uses that need it as an ingredient, the key one being ammonia for fertilisers (over transport).

"... so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn't stop to think if they should."

At least not at the moment.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.