Sunday Brunch: Are some industries really that 'hard to decarbonise'?

The decarbonisation challenge has two parts, technology and cost. In many cases we have a technological solution, we now need to focus on making it more cost competitive.

“However, some industrial and transport sub-sectors are significant greenhouse gas emitters and are harder to decarbonise due to their physical, technological or market-specific circumstances. Sectors that are particularly hard-to-abate include heavy-duty trucking, shipping, aviation, iron and steel, and chemicals and petrochemicals.― IRENA 2024

Most people I talk to think that 'hard to decarbonise' means that the known greener alternative technology doesn't yet work. That as much as we might want to, we don't have the solutions. And given this, it's understandable that change is not happening. But is this strictly correct? In many cases it's not true.

The challenge is normally not technology, it's cost. And this difference in phrasing is not academic, it tells us where we need to focus our attention.

While my training was as an engineer, after three decades I now mainly think like a finance person. And as a finance person I know that costs are not fixed, that humans are really good at finding ways of making products cheaper and cheaper. So, my first question is always, is this a cost or a technology challenge? And my second is is it likely that costs will decline over time?

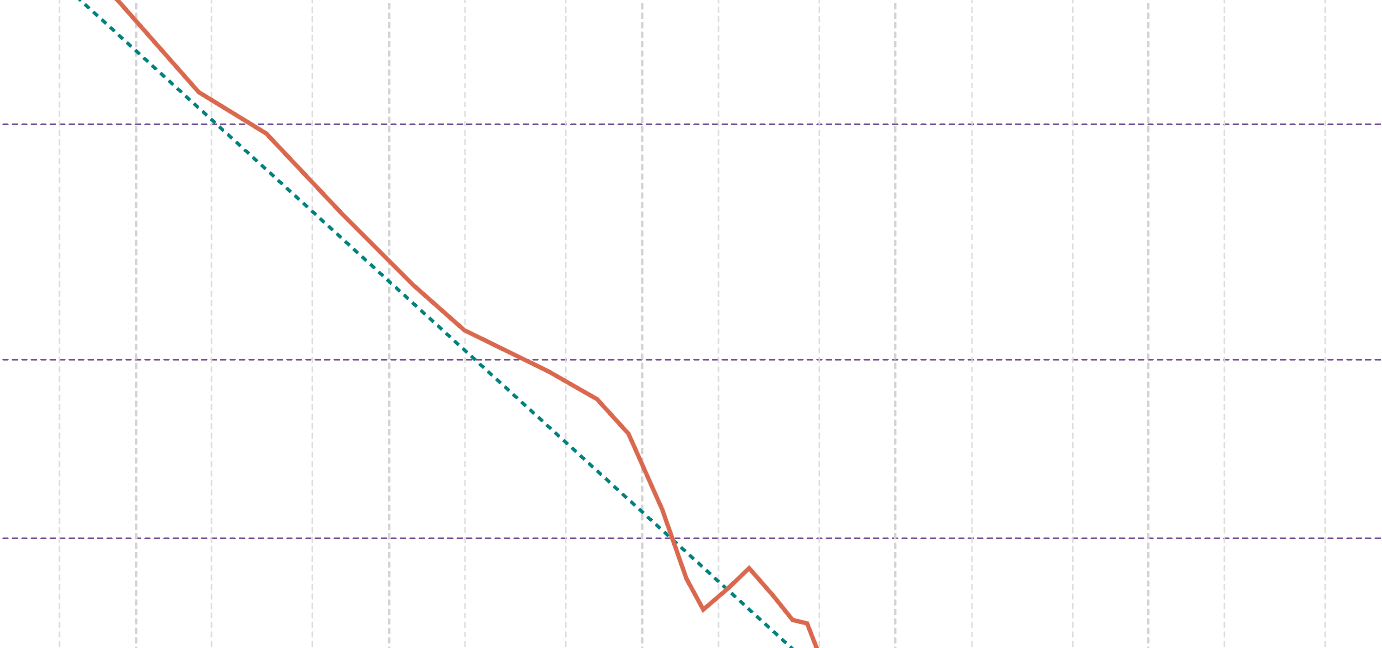

One framework that we need to talk about more is the learning curve. Put simply, the more we make of something, the cheaper it gets. Not always, but often enough.

As alternative solutions get cheaper, existing companies will experience more material challenges. The old way of doing things will be replaced.

So, maybe we need to stop calling them hard to de-carbonise industries and instead use Michael Liebreich's term ...'affordable to abate'.

Because that will help us better focus our attention on the important questions, which solutions can be cost competitive, and if they cannot, who should pay the difference?

Time to retire the phrase 'hard to de-carbonise'?

Akshat Rathi, who is a senior reporter on climate at Bloomberg News, also writes the Zero newsletter on LinkedIn. His work is always worth a read, it's free to subscribe to Zero. His latest blog on the use of the phrase 'hard to de-carbonise, got me thinking about how as investors we need to be very aware of how the words and phrases companies use matter, and how we need to always include innovation in our thinking about how the future will pan out.

The core of his argument is simple. We should not use the phrase hard to de-carbonise to describe industries where the solutions are available and known, but where they are not yet cost competitive. Because that distracts our attention from where the real work is needed.

If it's 'just' a cost issue, then we should be pushing for more research and development, policy support, and investments that take the solutions from pilots to full scale commercialisation. And where we think the alternative solution may never be as cheap as the fossil fuel based one (excluding externalities), we need to consider 'who pays' and how.

What we call things matters

It shouldn't be a shock to us, but it's something we often miss. How things get described impacts how we think about them. Describing industries as hard to de-carbonise suggests that inaction is actually not a bad idea, at least until we have a fully worked up, cost effective solution. But we know that our economy doesn't work this way. Innovation is the life blood of our economy, and innovation drives change.

We talked about this in a blog back in January 2023.

In the blog we referred to a landmark psychology paper, Tversky and Kahneman (1981, “The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice”), which concluded that there are “…predictable shifts of preference when the same problem is framed in different ways.” In other words, humans act in a certain way depending on how a problem is presented to them.

Consider the use of the term “the hydrogen economy”. This phrase is problematic as it leads us to the starting point that we have this commodity called hydrogen, and we need to find something to do with it. As Professor Maslow (1966, “The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance”) put it “If the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail.”

A more useful starting point is the work of the Hydrogen Science Coalition. They believe that while "innovative solutions like hydrogen are an important piece of the puzzle" to decarbonise the global economy, renewable hydrogen should deployed for "hard to decarbonise sectors, starting with where fossil hydrogen is used today."

A very different way of describing the challenge.

Innovation is already driving change, with more to come.

As Michael Liebreich wrote in his influential bog back in February 2024 (Net Zero Will Be Harder Than You Think – And Easier. Part II: Easier) ..

"for even the most challenging sectors we now have line of sight to decarbonization. In many cases we are seeing more than just pilots: in steel, fertilizers, mid-stream oil and gas, shipping, and even cement, billions of dollars are being invested"

Michael is a practical man, so he also points out that there are still substantial uncertainties. The debates about the best alternative can be found in shipping, steel making and fertiliser. The point is that we are now arguing about which solution is most viable, not if a solution exists.

One additional aspect that investors need to keep 'front of mind' is the innovation curve. The one that many of you will know is the cost of solar panels, which have declined by 99.6% since 1976. And if that is too long a period for you, they have halved since only 2012.

The point here is that innovation can fundamentally shift the balance of power in an industry. And sometimes it can happen faster than you expect. And that can massively impact the financial viability of 'old sunset industries. They can find themselves shifting from profitable to irrelevant in only a few decades.

To use my favourite Hemingway quote from The Sun Also Rises “How did you go bankrupt?" Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

And if a recent research paper from The Institute for New Economic Thinking at Oxford University is correct, then not only will change likely happen faster than we expect, but the economic benefits to all of us could be massive.

One last thought - who pays matters

Not all industries will find a viable alternative solution that is cheaper than existing fossil fuel based approaches. Policy measures and financial assistance might help, as would a carbon price. But as part of this process we need to think hard about who pays.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.