Sunday Brunch: ad singula or 'can I cut airline emissions by getting more people to fly?'

Individual carbon footprint calculations are useful in decision-making but a big picture view is also needed

"I've got this problem and I have to live with it. I can't do anything about it, it is a psychological thing and I can't explain it. I have not flown on a plane for two years."

Dennis Bergkamp, 1995

The quote above is from the Flying Dutchman, not the ghost ship doomed to sail the seven seas forever and never making port, but rather one of the greatest footballers I have had the pleasure to watch live. A hero to Arsenal fans, Dennis Bergkamp(1) had seemingly magical skill, pace (he was consistently in the top five fastest players at Arsenal during his time there), amazing vision and from 1994 he never flew. Bergkamp's aviophobia(2) stems from a combination of personal tragedy and an engine cut-out on a flight during the 1994 USA World Cup.

As well as aviophobes, many choose not to fly, or are anxious about flying, because of the impact of flying on global warming.

Aviation is an emotive topic and a confusing one. It is Schrodinger's CO2e emitter.

For an individual, taking a flight is likely to be their biggest individual emitting activity.

However as an industry overall it is one of the smaller ones, only contributing 2% - 3% of global CO2 emissions. Even factoring in its overall impact on global warming (taking into account persistent contrails that can trap heat) it contributes to around 3.5% of global warming.

The simple reason for this is that the majority of the population don't fly. Hannah Ritchie, Deputy Editor and Lead Research at Our World in Data and author of the excellent 'Sustainability by numbers' substack has a great article on this 👇🏾

But whilst I am going to talk about aviation, this Sunday Brunch really isn't about aviation. We shall do a more detailed blog on aviation at a later date.

Today's Sunday Brunch is really about top down versus bottom's up assessments of impact. How sometimes reducing the impact of an activity to the individual level can lead to suboptimal decisions or overlook potential avenues for improvement.

We'll take a look at two areas where there is a mismatch between an activity's proportional emissions contribution at the individual level versus the aggregate level: aviation and watching TV.

If you want to read the rest and are not already a member...

Do we need more or fewer Dennis Bergkamps?

Fewer people should fly. That way we can reduce carbon emissions. That is the frequent comment that I hear. I agree that not all flights are necessary or indeed quicker. I remember when I worked in Asia, I would often need to travel between Shanghai and Beijing. The flight was around 2 hours and 20 minutes, but when you factored in the check-in time and security at the airports either end, it was actually longer and more disruptive than taking the high speed rail (4.5 hour journey which was very smooth and fiendishly punctual).

There are numerous emissions calculators out there that will tell you what your carbon emissions are from taking a flight. Numbers vary but it is often quoted that for a typical short haul flight of around 1,000 miles (~ 1,700 km) around 0.5 tonnes of CO2 are emitted per person.

But it is actually planes flying that emit incremental CO2 not the people flying inside them.

To reduce carbon emissions from aviation, everything else being equal, we actually want fewer planes flying, not just people. Typically calculators use passenger load factors (or what the average percentage of filled seats is on a flight) of 82%. So there is an assumption that planes are not flying full. On a plane with 100 passengers, there would be 18 seats empty. That's on average. Some planes fly with even less. I remember a flight I took between Bogota in Colombia and Quito in Equador in 1998 where my two friends and I were the only passengers on the plane

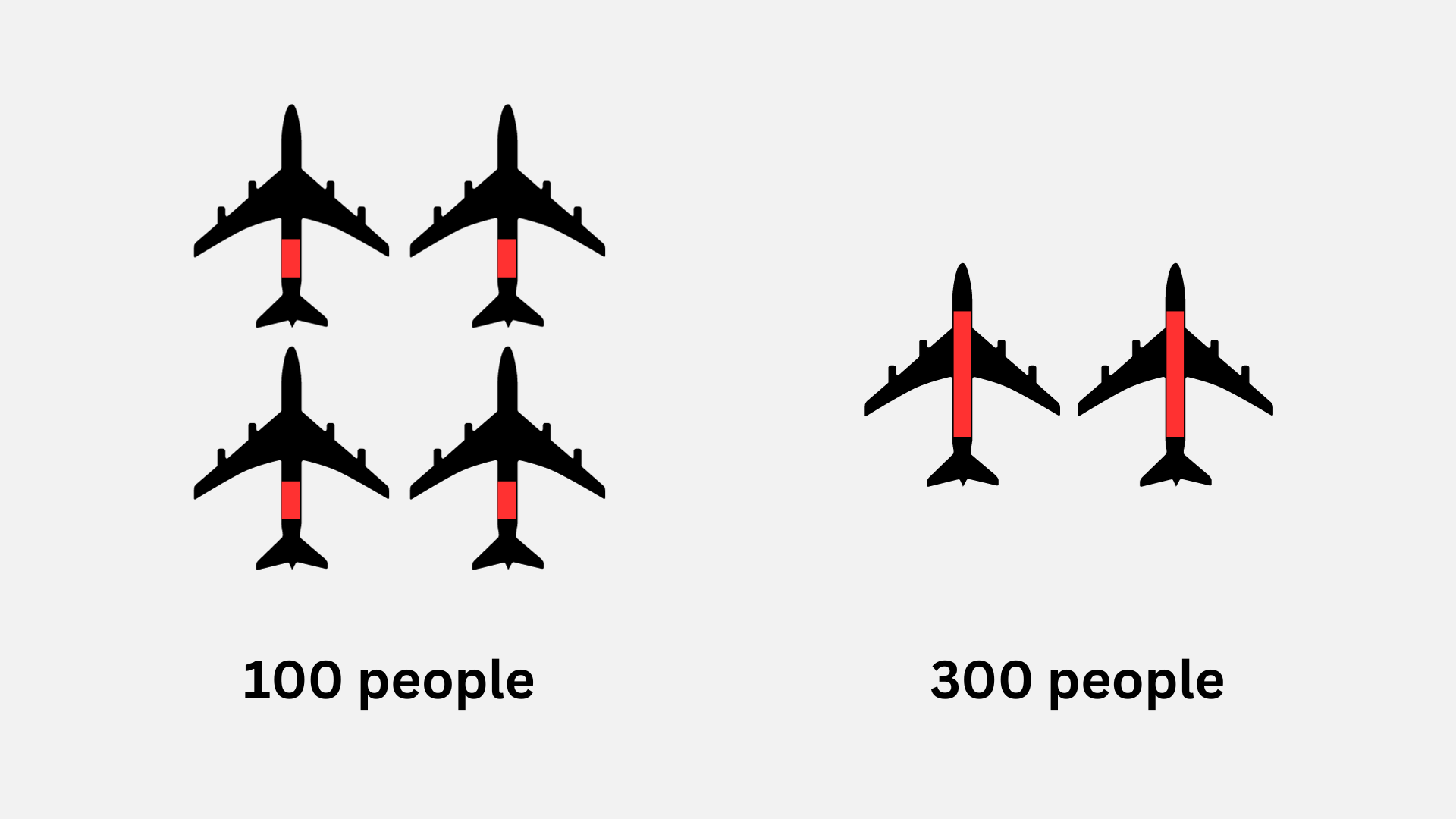

So a little thought experiment. Do 100 people or 300 people flying emit more CO2?

The reduction 'ad singula' computing an individual carbon footprint would clearly suggest the 300 people. 300 x 0.5 tonnes is bigger than 100 x 0.5 tonnes. However what if the 100 people were spread over 4 planes, whilst the 300 people were spread over 2?

Four planes flying would emit more than two equal planes flying.

There is clearly more to it (weight of the passengers and their luggage etc) but the point of the exercise is that when we reduce to the individual we can sometimes miss things.

Indeed an incremental passenger on a not full flight who then buys a verified carbon offset is even providing additionality relative to someone who chooses not to fly and not buy an offset. I am not advocating that we should get more people flying without limit but just that the pathway to reduction is not smooth.

The choir of many voices?

So with aviation there is the confusing issue that taking a flight for an individual is likely to be far and away their biggest CO2e emitting activity but given that the vast majority of the population do not fly, that the industry's contribution is lower than many other sectors.

Sometimes an activity may have such a small incremental impact for an individual that they wonder whether it is worth making a change - i.e. i'm not really making a difference so why bother?

In Mike Berners-Lee’s book, "How Bad are Bananas?: The Carbon Footprint of Everything", there is a statement that an individual watching TV for a year has a similar carbon footprint to driving a car for 500 miles - just over 200kg of CO2 in a year. That is not that big when compared with the approximately 2.2 tonnes of CO2 that the average UK household gas boiler produces heating a home for year.

The impact of an individual watching TV for a year is small. But when you add up all of the TV watching across the globe, it makes a meaningful impact. According to Earthweb (and their sources), more than 1.72 billion homes worldwide own a TV set. That's just over 20% as big as the global cement industry (1.67 billion tonnes per annum).

We discussed digital sustainability (including TV) in this Deep Dive 👇🏾

Know your drivers

OK so I know the title of the blog made it seem like this was a blog about aviation. I did say at the start though that it wasn't.

With aviation it is the aircraft flying that produce the bulk of the global warming impact not the people (or the cargo) themselves. Yes there will be tipping points where fewer people flying does lead to fewer aircraft flying, but improving capacity utilisation (load factors) is an avenue worth investigating too, along with power source (Sustainable Aviation Fuels, battery electric etc), route optimisation (including altitude and reducing likelihood of contrail formation etc) are all areas that can bring the balance between the necessity to fly in some circumstances with the very real impact that flying overall has on global warming.

The 'watching TV' example shows us that even if an activity at the individual level has a tiny impact, the aggregation of many, many people doing it means that it is an important to focus on. Digital sustainability is a focus with a number of areas being investigated highlighted in the blog above. Most recently, Danfoss, Google, Microsoft and Schneider Electric have formed a consortium aimed at uncovering solutions to held reduce emissions from data centres across Europe.

Both examples illustrate how trying to reduce everything down to an individual impact can lead to suboptimal decisions or overlook potential avenues for improvement. Having said that information at the individual level can help amass collective actions that ultimately create the tipping points for positive change.

For sustainability professionals involved in strategic conversations understanding the marriage between big picture and individual level is critical to getting to workable and financially viable solutions.

Notes:

(1) If you are not familiar with Dennis Bergkamp here is a showreel. Arsenal paid £7.5 million for him in 1995...

(2) Aviophobia, which is a fear of flying, is also known as pteromerhanophobia. Here is the most famous fictional pteromerhanophobic, in my opinion: BA Baracus from The A-Team:

Ironically 'pteromerhanophobia' is not even close to being the longest phobia word. That word is 'hippopotomonstrosesquippedaliophobia', which is the name for a fear of long words.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.