Will Sustainable Aviation Fuel make airlines sustainable?

Unless aviation gets political priority, SAF looks like its going to struggle to be a financially viable decarbonisation solution for the aviation industry.

Summary: Sustainable Aviation Fuels or SAF's have the potential to replace some (maybe most) of the fossil fuels used to produce jet kerosene. This could reduce, but not eliminate the industry's Green House Gas (GHG) emissions. But, there are some material obstacles to overcome including cost, and an absence of enough suitable biological feedstocks. The cost aspect looks solvable, but the feedstock challenge could be more material.

Why this is important: Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) is a core element in the aviation industry plans to deliver on their net zero pledges. While electric planes (and maybe one day green hydrogen ones) are possible, its highly likely that we will be relying on traditional jet engines for a long time, maybe a decade or more. This means even if we can find ways of reducing our desire to fly, the industry is going to need SAF at scale.

The big theme: Before the pandemic, in 2019, aviation accounted for about 3.1% of total global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel combustion, and the number of passenger miles traveled each year was rising. If aviation emissions were a country, that would make it the sixth-largest emitter, closely following Japan. While aviation is not the largest GHG emitting sector, demand growth means the problem gets larger as each year goes by.

I expected this to be an easy blog to write. We know that aviation will probably be one of the later major industrial sectors to fully decarbonise. The most financially sensible path for the airline industry is to find a 'drop in' fuel technology, that works in existing jet engines. One that generates lower GHG emissions, making it a good bridging technology for the next decade or maybe a bit more.

And then, as aircraft get replaced, they can gradually transition to electric aircraft for short and medium haul, and maybe hydrogen for long haul (the later part of the plan still needs some thought).

And Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) looks like the perfect answer. It is a type of biofuel that can currently replace 50% of jet fuel, and 100% replacement looks to be deliverable. Properly produced it massively cuts end to end GHG emissions. Yes, its expensive, but not so expensive that we cannot find solutions.

BUT - to produce enough we apparently need to use most of the potential biofuel feedstocks. AND a lot of other industries are already saying 'biofuels are the answer to our decarbonisation challenge' as well. So, while each solution makes sense on its own, if you add them together, we have a raw material shortfall.

And our politicians are fudging. They are not saying 'this solution has priority', but instead they are pretending (greenwashing) that we can deliver on all of the solutions. We face some hard decisions. Let's make them informed decisions. Unless aviation gets political priority, SAF looks like its going to struggle to be a financially viable decarbonisation solution for the aviation industry.

The Detail

Summary of a study to be published in Nature Sustainability

- The idea of jetliners running solely on fuel made from used cooking oil from restaurants or corn stalks might seem futuristic, but it’s not that far away. Airlines are already experimenting with sustainable aviation fuels, including biofuels made from agriculture residues, trees, corn and used cooking oil, and synthetic fuels made with captured carbon and green hydrogen. Before the pandemic, in 2019, aviation accounted for about 3.1% of total global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel combustion, and the number of passenger miles traveled each year was rising. If aviation emissions were a country, that would make it the sixth-largest emitter, closely following Japan.

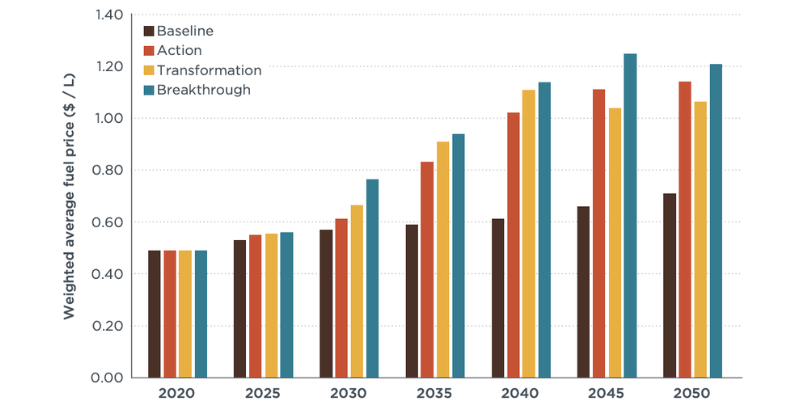

- But, a rapid expansion in biofuel sustainable aviation fuels is easier said than done. It could require as much as 1.2 million square miles (300 million hectares) of dedicated land to grow crops to turn into fuel – roughly 19% of global cropland today. Another challenge is cost. The global average price of fossil jet fuel is about about US$3 per gallon ($0.80 per liter), while the cost to produce bio-based jet fuels is often more than twice as much. The cheapest, HEFA, which uses fats, oils and greases, ranges in cost from $2.95 to $8.67 per gallon ($0.78 to $2.29 per liter), but it depends on the availability of waste oil.

Why this is important

Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) is an alternative to conventional fossil aviation fuel, as it's produced with biological and non-biological resources not fossil fuels. The feedstocks can be derived from both plant and animal materials, ranging from cooking oil and plant oils, to agricultural residues, as well as municipal waste and waste gases.

- Aviation draws a lot of criticism from many environmental groups, in part because its seen by some as an avoidable source of GHG emissions. We just need to fly less and use ground transportation more. Looking at the numbers, it's contribution to GHG emissions is complex. According to Our World in Data:

As well as emitting CO2 from burning fuel, planes affect the concentration of other gases and pollutants in the atmosphere. They result in a short-term increase, but long-term decrease in ozone (O3); a decrease in methane (CH4); emissions of water vapour; soot; sulfur aerosols; and water contrails. While some of these impacts result in warming, others induce a cooling effect. Overall, the warming effect is stronger.

- The bottom line is that it is estimated that aviation accounts for just over 3% of the emissions that cause global warming. Aviation's CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels account for less than half of this (c. 1.7%). The other big source is what is called non-CO2 forcings, and within this contrails – water vapor trails from aircraft exhausts – account for the largest share.

Lets start with what we make SAF with

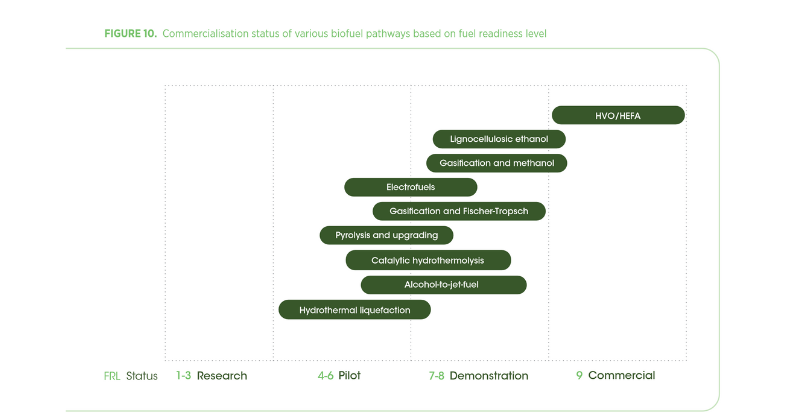

- There are in fact multiple ways to produce SAF. In that sense it's an umbrella term used to cover aviation fuels made with a wide range of feedstocks. At present there are seven technology pathways approved by the American Society for Testing and Materials.

- These can be grouped into five main categories: hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids (HEFA), alcohol to- jet (ATJ), Fischer-Tropsch (FT), hydrothermolysis and microbial conversion. HEFA is the only one working at an industrial scale. It has a projected capacity of approximately 90,000 barrels per day by 2025. Most SAF is currently produced from fats, oils and greases (FOGs) using this HEFA process. But, because we have a limited amount of fat, oil and grease waste, the HEFA technology looks like it can replace no more than 10% of current aviation fuel demand.

- We will be digging down into the various technologies in a later Perspective or Deep Dive blog. For now you just need to know that most SAF currently comes from the HERA process, using fats, oils and greases, but that other technologies do exist. And these alternative technologies will start to become more important, because they use different raw materials: materials that we potentially have a much larger supply of. They are how, in the future, we could produce the SAF needed to replace 100% of aviation fuel demand.

How much potential raw material do we have to make biofuels?

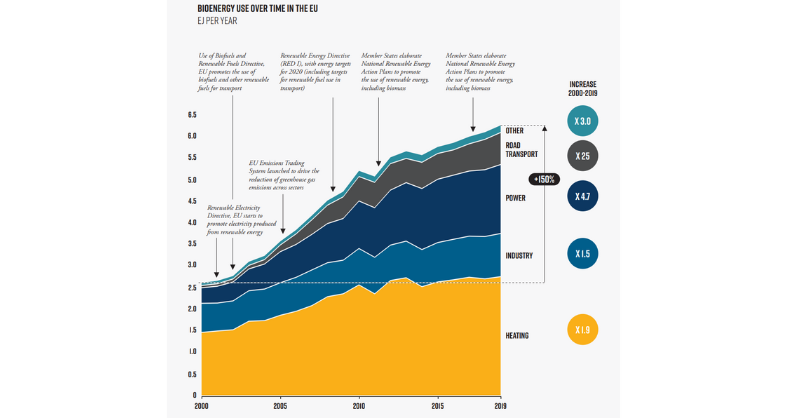

- The answer to this question is - it depends. Part of the challenge is that we already use a lot of the existing 'waste' biofuel material in other processes and end uses. For instance, in the European Union just over 40% of biomass is used to produce materials such as wood products, and for pulp and paper production. Only small volumes of biomaterials are currently used for textiles and chemicals, but those subsectors are expected to grow fast. Other large existing applications are electricity and heat generation, and fuel for road transport. And the use of bioenergy has increased dramatically, up 150% since 2000. One number to hold in your head is the total use is now over 6.0 EJ - it's not the units you need to remember, it's just the number.

But perhaps this isn't a problem. Maybe we could produce a lot more bioenergy raw materials. Well, yes and no. The chart above is from a report by Material Economics and they estimated that the total bioenergy supply in Europe was currently 10.2 EJ. And that by 2050, the supply could be 11-13EJ, and maybe get as high as 20EJ. That looks fairly encouraging. The number I asked you to remember, how much Europe already used, was 6EJ. So potentially a lot of extra supply, for things like SAF.

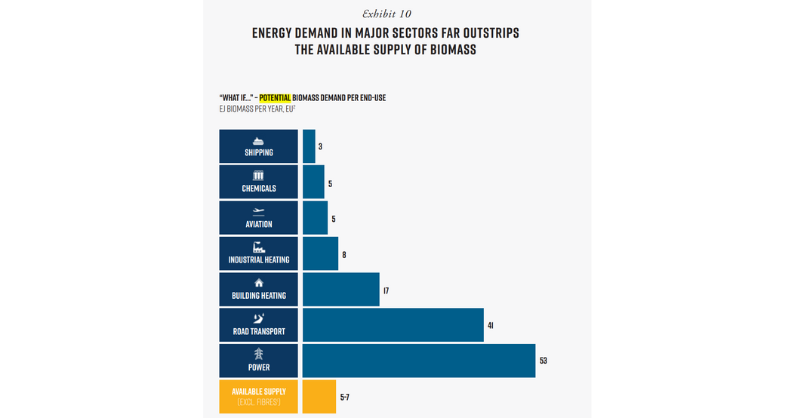

But, and this is where we get to the potential financial deal breaker, a lot of other industries are also looking at biofuels as a way of decarbonising. These include shipping, chemicals, heating, and electricity generation. And if you add all of these up, you get a demand level well above expected supply.

- And why do we say financial deal breaker. In the absence of governments setting priorities, or more strictly saying to some key industries 'you cannot use biofuels, we are saving them for aviation', then the market will decide. The suppliers will, all other things being equal, sell to the customer that is willing to pay the most.

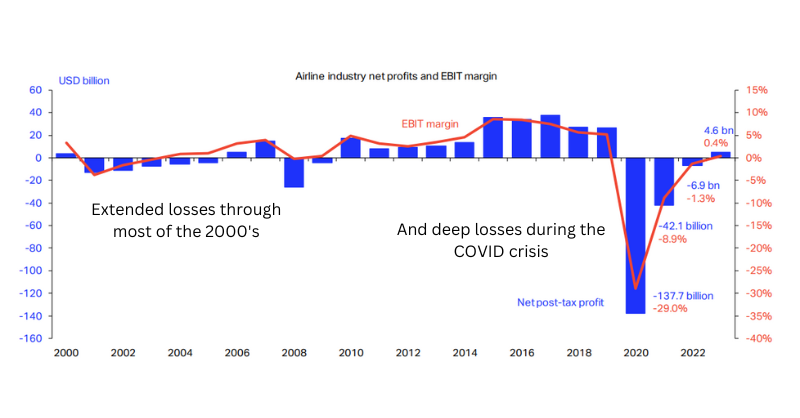

- And that is unlikely to be aviation. Airline industry profitability is often a challenge. All sorts of issues can blow them off their planned financial course, from volcanoes, to terrorist attacks, and global recessions. The chart below shows (blue bars) the industry profitability over the last 22 years. While some periods, say 2010 to 2017, were good, others were disasters. This is not an industry that wants to get into a bidding war for SAF supply.

How much does SAF cost?

- It will come as no surprise that SAF is more expensive that traditional jet fuel. Let's pretend for a moment that we could produce enough SAF to replace most of the jet fuel that the industry currently uses. How much would this cost, or asking a better question, by how much would this increase input costs for the airlines?

- In a 2022 report, the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) estimated that SAF blending consistent with a 1.75 degree C global temperature cap (their breakthrough scenario) would increase airline fuel costs in 2030 by approximately 35%. And the aviation industry body IATA, estimated that in 2022 jet fuel costs would make up c. 30% of total airline operating expenses (based off an average oil price of US$103.2/barrel of Brent). So a back of the envelope calculation suggests that the use of SAF to achieve the ICCT breakthrough scenario would add c. 10% to costs, and probably add a similar amount to ticket prices.

- This means one key question is 'will airlines voluntarily increase ticket prices by 10% (or more)' to pay for SAF? We think the short financial answer to this is no. The airline industry is cost competitive and the rise of low cost airlines 'proved' that low fares are popular. The core problem is that airlines won’t voluntarily pay more for fuel, unless the playing field is level. Which means either everyone has to do it, or the cost is subsidised. And all of this assumes of course that we have neough supply.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.