When a focus on productivity leads to system inefficiency

Rethinking how we view 'success' in farming could ensure the global population has sufficient nutrients.

Summary: The 2018 Farm Act is up for renewal imminently with critics pointing out that it disproportionately benefits 'big agriculture'. An alternative proposed bill, whilst unlikely to pass, has garnered support and brought attention to wider stakeholder interests. With a number of megatrends converging - climate change, biodiversity loss, water scarcity and food security - the agriculture sector globally needs innovation and reform. Historically, investment in agriculture has been focused on increasing yields or increasing farm productivity - from research into pesticides and fertilisers through to agtech designed to irrigate, cultivate and process more efficiently. However, could it be that a focus on farm productivity actually promotes system inefficiency? We discuss a proposal from Chatham House that suggests a shift in focus from yields per unit input or ‘Total Farm Productivity’ to the number of people that can be fed healthily and sustainably per unit input or ‘‘Total Resource Productivity’.

Why this is important: Many larger investible companies rely on our agricultural supply chains (think food producers and supermarkets for instance), so it’s a big long-term issue all investors should be considering. Recent food supply disruption and price inflation will bring it more to the fore.

The big theme: Agriculture (and its sibling, aquaculture) sit at the intersection of a number of UN Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs). As one reads through the list of goals they are either directly relevant (for example goal 2: zero hunger or goal 3: good health and well-being) or have a causal relationship (for example, education improving with better nutrition and less pollution). Reforming agriculture is a big deal, in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, environmental impact, food security and rural society. It’s going to require massive social and economic change and disruption, to production methods, to supply chains and to employment.

The details

"We simply pay too much to the wrong people, to grow the wrong foods the wrong way, in the wrong places"

Earl Blumenauer, US representative for Oregon's 3rd congressional district.

Every 5 years in the US, the package of agricultural and food policies is renewed with the next renewal imminent. The Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 better known as the '2018 Farm Act' comprises a number of programs including nutrition assistance (76% of total outlays), crop insurance (9%), commodity support (7%) and conservation (7%).

Approximately $63 billion of the total outlays was for subsidies with 70% going to just 10% of farms most of which produce commodity crops - often used to make animal feed - and in 2019 10% of funding went to concentrated animal feeding operations.

We discussed issues with animal feed in a recent blog 👇🏾

This is a problem for Rep. Blumenauer who is proposing a new plan as an alternative. His Food and Farm Act, looks to redirect subsidies away from large-scale, energy-intensive commodity crop farms towards environmentally friendly agriculture, small farmers and healthy food access. It would also prioritise food waste management and animal welfare.

Whilst unlikely to pass, it has received some high profile endorsements from a broad range of areas including food writers, food justice organisations, environmental and animal welfare groups.

At its heart is a focus on the overall system and not 'big agriculture' bringing together a number of stakeholder needs including resiliency, local food security and access, climate change and biodiversity and support for local farms.

Historically, investment in agriculture has been focused on increasing yields - from research into pesticides and fertilisers through to agtech designed to irrigate, cultivate and process more efficiently.

However, could it be that a focus on farm productivity actually promotes system inefficiency?

A complete overhaul: Shift focus from just increasing yield, to improving the total system efficiency.

This interesting hypothesis is put forward by Tim Benton and Rob Bailey from the Energy, Environment and Resources Department at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House. The key is where that focus is. They propose shifting the current policy focus for food from yields per unit input or ‘Total Farm Productivity’ to the number of people that can be fed healthily and sustainably per unit input or ‘‘Total Resource Productivity’. This would, in their view, increase the efficiency of the overall food system.

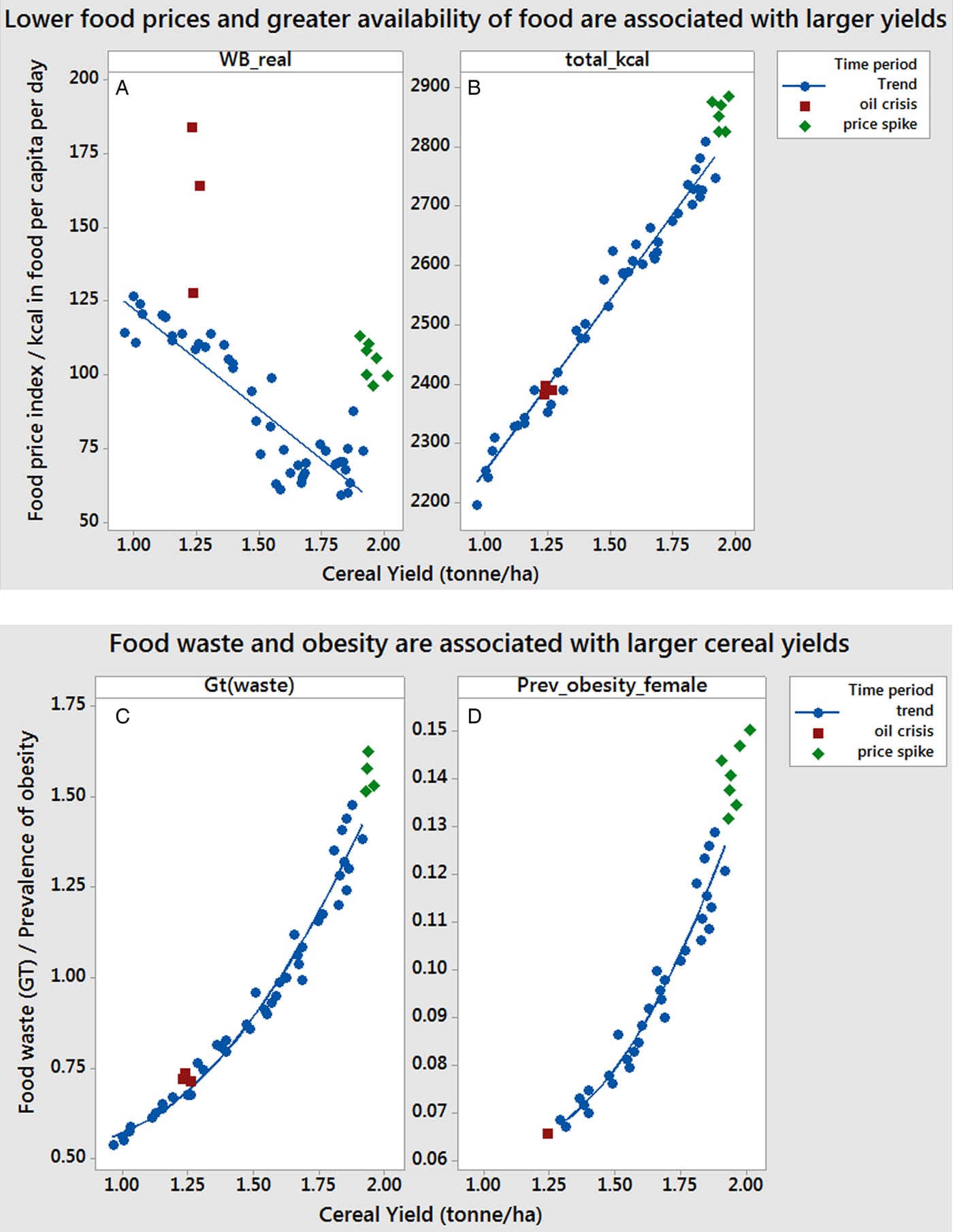

The focus on ‘yields per unit input’ has led to a massive growth in agricultural produce supply and subsequent declines in price. However, the availability of increasingly cheaper calories has led to a vicious circle of increasing demand for cheaper production, driving damage to the environment, increasing waste, and higher levels of obesity (now exceeding the prevalence of underweight).

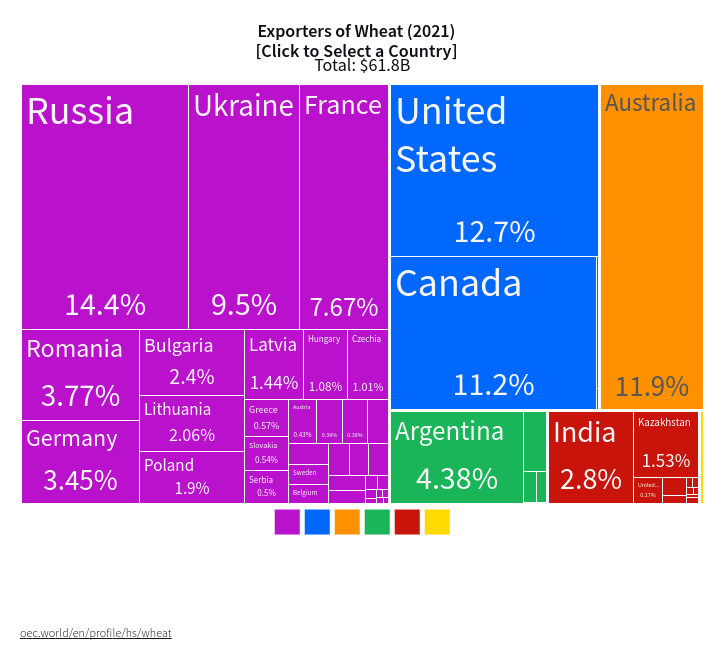

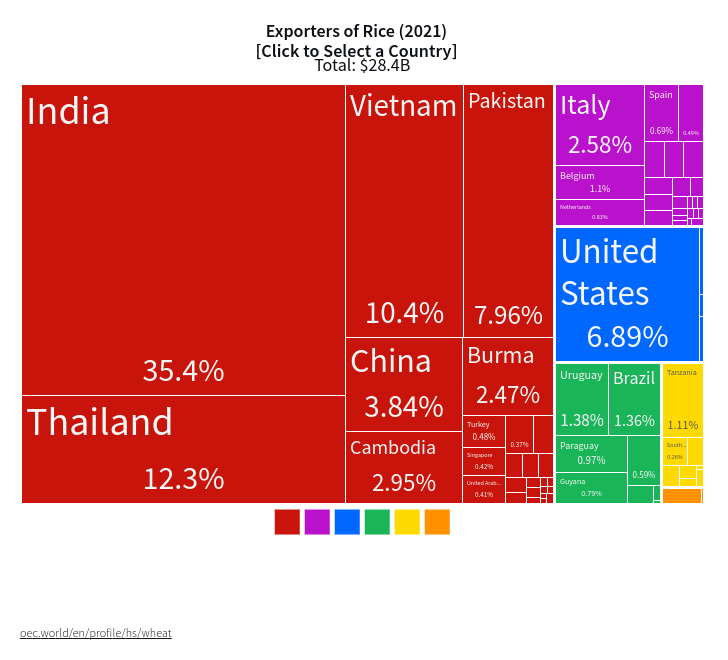

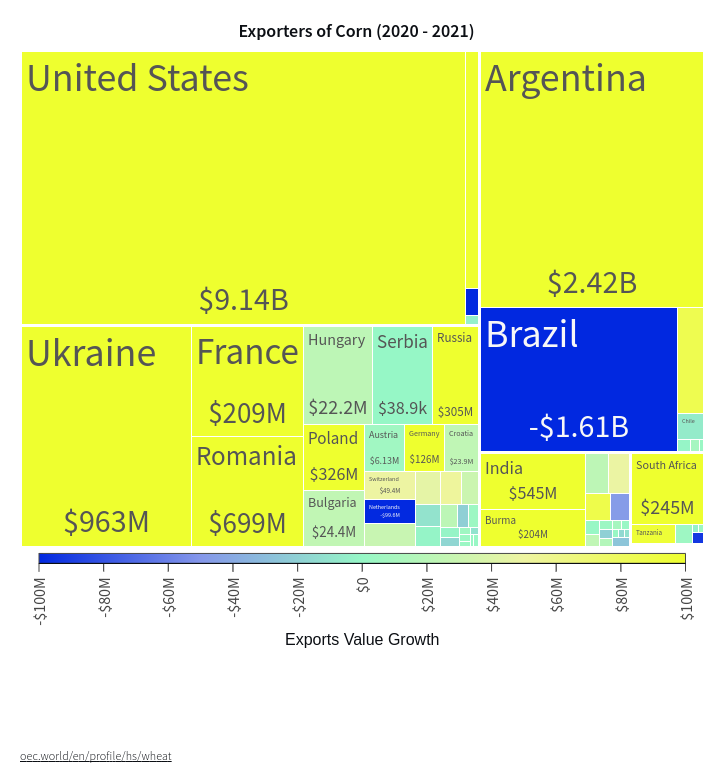

Measured as the amount of food grown that is eaten by humans, the current inefficiency in the global food system is a result of the drive for efficiency at the farm level - the “paradox of productivity.” Production has become specialised on a small number of highly productive crops crowding out traditionally grown varieties and creating a dependency risk on certain areas of the world (e.g. the so called ‘breadbasket’ or 'ricebowl' areas).

(Source: OEC, CCO public domain)

More than 50% of the world’s crop calories as of 2014 came from just 3 things: wheat, rice and maize. More than three-quarters of all crop calories came from those three plus sugar, barley, soy, palm and potato.

Why this is important

Although this paper was published in April 2019 (how did we miss it then?) it is still very much relevant today - hence why we are repeating it. As mentioned previously, most agricultural innovation historically has been focused on improving yields. However, there have also been a number of rather obvious yield improving measures that have been ignored.

These include wasted fruit and vegetables at the point of harvesting for not being the right shape, through to surplus fresh food thrown away at the point of sale or in our homes. In the UK for example it is estimated that 3 million tonnes of good, edible surplus food is thrown away each year. UN Sustainable Development Goal 12.3 aims to halve food waste at the retail and consumer level and to reduce food loss across supply chains.

There is also a climate change imperative. Food waste itself generates a large amount of GHG emissions. It is estimated that if food waste were a country, it would be the third largest emitting country in the world (between 8% and 10% of global GHG emissions).

The authors put forward a number of individual policy measures to achieve their aim including cross-disciplinary, cross-sectoral framings of the issues, incorporating social and environmental costs into food prices (balancing the implied regressiveness with improving intergenerational equity), greater contribution from governments on the debate, rebalancing of subsidies to agriculture, reducing waste throughout the chain, new technologies and new norms (such as veganism, vegetarianism and flexitarianism).

What other issues does this raise?

The yield improvement focus has led to a reduction in the variety of crops providing calories with a focus on a small number of crops. The creation of hardier strains of wheat through cross-breeding, for example, has produced strains that contain novel proteins that are hard for many to digest. A return to a broader set of crops can not only potentially help reduce inflammation but also there is an important social aspect in encouraging the growth of local and indigenous communities, increasing subsistence and rejuvenating local areas.

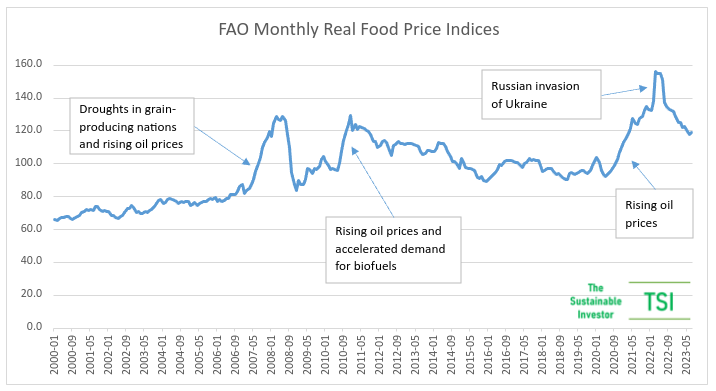

From a risk management point of view, it can also potentially stabilise food prices by improving food security through diversification - the Ukraine conflict drove the FAO Food Price Index up 12.6% in March 2022 month on month.

From an investment perspective, there are a number of interesting areas for development. The removal of expiry dates and the marketing of so-called “wonky fruit and vegetables” reduces waste at supermarkets and can have a financial benefit too. When Morrisons brought in their wonky produce line, it boosted its own-label sales by 18%.

Vertical farming could be a low footprint way of producing all manner of produce and it can even reduce stocking times and transport costs and emissions by locating within retail stores.

Taking the previous point further, the relocation and dispersion of food production to be closer to the point of consumption will also have implications for associated infrastructure such as cold chain logistics (freezing food at point of harvest is a way of reducing waste too), employment migration and seasonal consumption.

Conclusion

As a major source of GHG emissions, water usage and a vector for antimicrobial resistance propagation (see our AMR Primer), the agricultural industry is in need of reform. This will not be easy, but there are steps that can be taken to ensure that we get the nutrition we need in harmony with both planet and population.

This blog was previously published as part of a Deep Dive "Feed the world - changes to feed and Total Resource Productivity". We have updated and republished it to include some recent developments.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.