The good stuff in wastewater - part 1

In a world of increasingly scarce resources, wastewater can provide us with heat (for our buildings) plus raw materials for fertiliser and for energy. It now makes sense to better use the good stuff in our waste water - that we are currently just wasting.

Summary: In a world of increasingly scarce resources, wastewater can provide us with heat (for our buildings) plus raw materials for fertiliser and for energy. It now makes sense to better use the good stuff in our waste water - resources that we are currently just wasting.

Why this is important: We tend to think about wastewater treatment as being an environmental and health issue. That is why we treat our sewage rather than just pump it into rivers and the sea. But in our growing circular economy, recycling the resources in our wastewater increasingly makes financial sense.

The big theme: In their 2021 update, UN Water estimated that globally nearly half of household water flows were NOT safely treated. And the data shows massive variations, with the lowest levels of treatment in Central and Southern Asia & Sub Saharan Africa. Funding this is a massive challenge, so finding alternative revenue streams can really help.

The details

Summary of an article published in Egalite

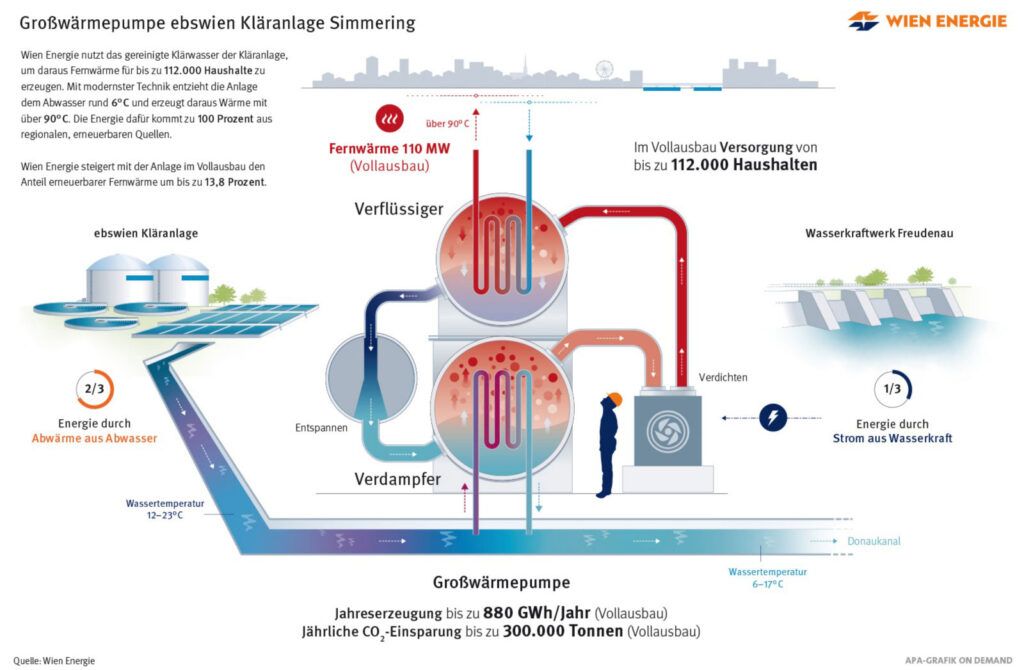

- Company Vienna Energy is preparing to test the largest heat pump in Europe to obtain energy from domestic wastewater. According to the company, the heat pumps will extract heat from the already treated wastewater, using it to generate hot water at c. 90 degrees. The first stage of the project, due to be completed this year, will enable them to generate enough energy to heat 56,000 households. This will rise to 112,000 households by 2027, or roughly one quarter of all of the households on the current district heating grid. The total project is estimated to cost c. €70m.

Why this is important

- One of my first jobs as a young and recently graduated civil engineer, was to work on parts of a new waste water system for the city of Wellington. A key part of the plan was the construction of a long outlet that took the waste out into the Cook Strait. Yes, it was dumped at sea, mostly untreated. The world has moved on since then. For instance, the European Environment Agency estimates that the bulk of European countries now "safely treat" their domestic waste water before discharge. But even here, there are still 10 countries where the treatment rate is below 80%.

- And, in their 2021 update, UN Water estimated that globally only 56% of household water flows were safely treated. So better but still a long way to go. And if you live as I do in the UK, you will have a degree of scepticism about these figures, given that we seem to pump raw sewerage into our rivers on a regular basis, mostly when it rains. And its important to remember that building a waste treatment plant is only part of the cost. Laying the pipe network that gets the wastewater to the treatment station, and keeping it maintained, is also a big cost element.

- There are all sorts of public health and environmental protection reasons why we treat wastewater. But for this blog I want to begin to explore another aspect, the good things in our wastewater that we currently just dump into our seas and waterways. In part because we want to better use our existing resources, but also because they can provide an alternative revenue stream that can, at least in part, fund the wastewater treatment process. What do I mean by wasted resources? The first is heat, as highlighted by the Vienna example above. But there is also nitrogen and phosphorus (essential elements in fertiliser) and then there is sludge to energy.

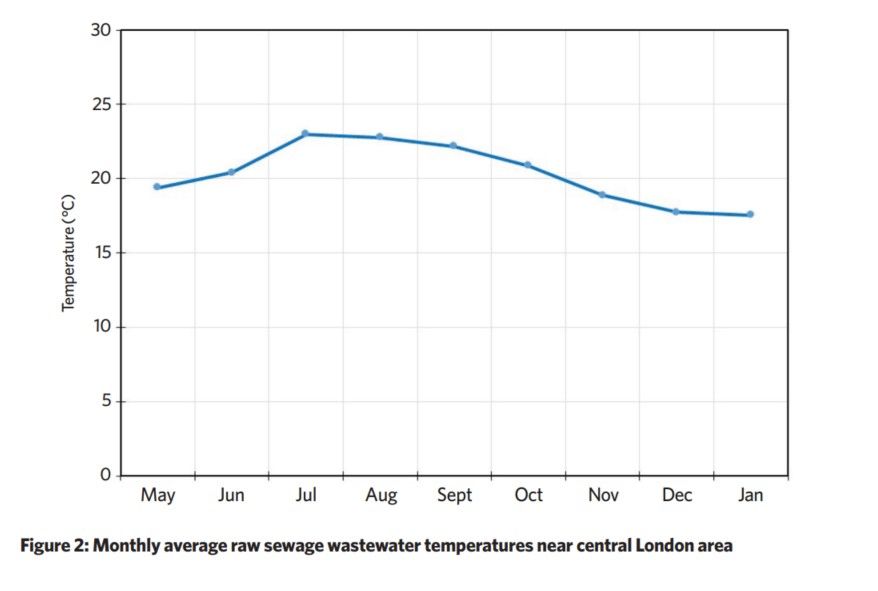

- Lets start today with heat. Most wastewater outflows are warmer than the rivers into which they flow. Temperatures at the input side range between 18 degrees and 23 degrees C, depending on the season. And by the time it is processed and ready to pump into the river or sea, a typical temperature is 12 - 15 degrees C, and they hold this temperature pretty much all year round.

- So how can we use this "surplus heat"? If you are a regular reader of our blogs, you can probably work out what could happen next - yes, its heat pumps.

- The heat pump extracts the surplus heat from the wastewater via a heat exchanger, and it can then be used for either district heating or for commercial applications such as heating greenhouses. Now, this might not sound like a big deal, a little bit of heat from a wastewater treatment station is hardly going to move the dial, is it? Well think again.

- The heated water from our showers, dishwashers and washing machines goes down the drain, quite literally, and into the sewer. In Switzerland, it is estimated that 6TWh of thermal energy are lost every year through the sewage system, corresponding to around 7% of the country’s total demand for space and hot-water heating. And in the USA, the figure is higher, with Americans estimated to flush a massive 350TWh of energy down the drain each year – the equivalent of heating 30 million homes a year. In the UK, energy from the 16 billion litres of sewage wastewater dumped in the sewers every day could, theoretically, provide more than 20TWh of heat energy annually. This is enough to provide space heating and hot water to 1.6 million homes.

- But if this is true, then surely its widely used. After all, who would let all of this waste heat go to, well waste? The short answer is yes, there are some examples, but it's not yet a widely used technology. One set of examples are in Sweden. Here the heat pumps use the waste heat as it leaves the buildings, so before it even gets to the wastewater treatment station. Given this, its not surprising these schemes are smaller - so multi occupancy dwellings of between 150 and 300 households, or in one example, an office, hotel and supermarket complex.

- And a new project are being planned in Denver, providing heating for a 250 acre site that will be a hub for art, education and agriculture. This is another example of taking heat from sewer pipes, this time the main sewer line as it passes the site. Plus, Thames Water and the London Borough of Kingston have recently unveiled plans to use heat recovered from a wastewater treatment plant to provide low carbon heating for more than 2,000 homes.

- What might give this technology a boost. One reason is the pressure on local government spending, finding new revenue streams helps here. Plus, a number of European countries are looking to ban fossil fuel building heating systems, with the Dutch & German examples (no new systems installed after 2026 in the Netherlands and only hybrid systems after 2024 in Germany) being some of the more demanding. For some consumers heat pumps look like a good alternative. But in many markets the installation cost (and hassle) is still an issue. So, at least some of the heating load will need to be carried by district heating. Which is where extracting "waste" heat from our wastewater systems can play a role. Plus of course, finding alternative revenue sources for a wastewater system build could be the factor that tips a project from too expensive to viable.

- In future blogs we will explore the potential for nitrogen and phosphorous extraction (not totally straightforward, but still possible) and of course the much bigger topic of sludge to energy. This later technology is already mature, but not used anywhere near as often as it could be.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.