Coping better with extreme events

Sustainability is not just about mitigation (actions that reduce future risks). In some cases the challenge is much more immediate, we also need to invest in adaption. Helping us to cope with events that are happening now.

At a time when our press coverage is dominated by wildfires (and it will be flood and hurricane season soon) it's worth remembering that sustainability is not just about mitigation (actions that reduce future risks). In some cases the challenge is much more immediate, we also need to invest in adaption. Helping us to cope with events that are happening now.

Some adaption requires material capital investment, managing forests to reduce fire risk, building flood and tidal protection infrastructure, constructing dams to provide water, and dredging our waterways. But adaption is also about being prepared, having systems and structures in place that help when disasters happen.

As extreme events become more commonplace, we need to get better at helping people cope during the disaster, and getting their lives back on track afterwards. This means improving our disaster response. Where can people go if their house/hotel is at risk of storms, flooding or fire? Is the base for the emergency services secure and accessible? And where can people obtain useful information and basics such as electricity for their phones?

Plus, after the disaster, do we have a hub that the communities can use to support the recovery - everything from offices for support services and insurance claims teams, through to somewhere that food, electricity and water can be stored and distributed.

One important element of this improved response are what are known as resilience hubs. And we need to stop thinking about them as wasted money if we don't use them. And start thinking instead that these are facilities we will be really pleased we have when disaster strikes.

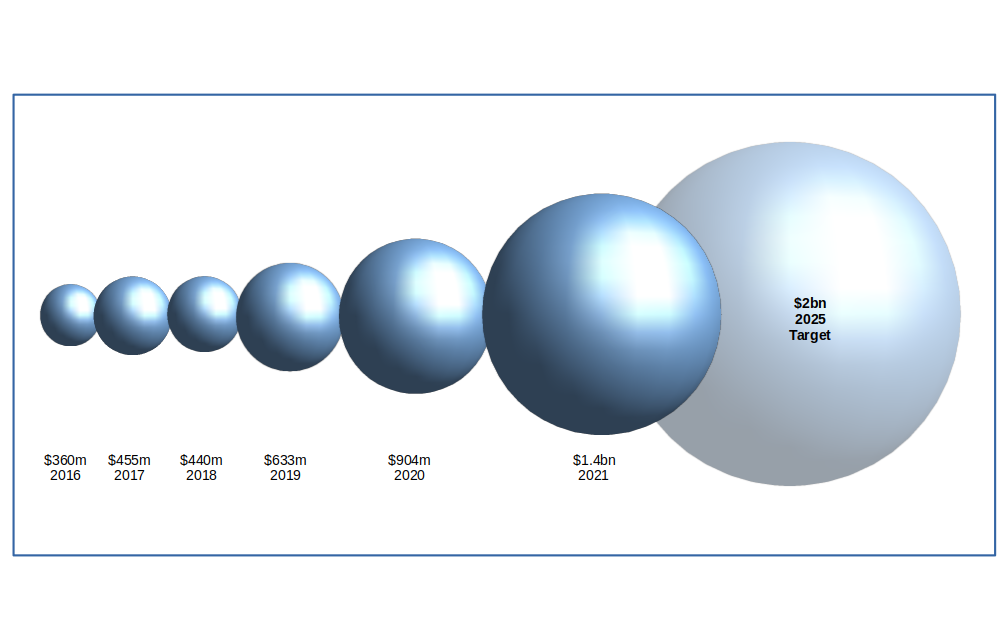

The UN estimates that climate adaptation spending, just in developing countries, could reach $300bn by 2030. This is on top of the tens of billions being spent by national and regional governments in developed countries. This covers a range of investment themes, including construction of flood defences, building resilience into our essential services, and enhancing disaster responses.

The details

Summary of a story from RMI on Weathering Climate Disasters with Resilience Hubs

- Resilience hubs are physical, community-serving facilities that support residents, distribute needed resources, reduce carbon pollution, and enhance quality of life. Resilience hubs offer local governments a powerful means of supporting vulnerable populations before, during, and after an extreme weather event or other disasters. Depending on the needs of the communities where hubs are located, they can support resilience across five foundational areas — ensuring reliable power, coordinating communication, providing dependable facilities, managing operations, and offering valuable services and programming.

- Enhancing energy efficiency at a resilience hub can increase “hours of safety” — a measurement of how long a building can maintain a safe, comfortable temperature when the power goes out. Resilience hubs with solar and storage can be especially impactful for disadvantaged communities. In the case of Storm Uri (Texas 2021) low-income communities who did not live on “critical circuits” with hospitals or other critical infrastructure experienced longer power outages — some up to four days — as the limited power available was prioritized elsewhere.

Why this is important

We have all seen the recent images of tourists and locals fleeing wildfires. And if you think back to last winter it was hurricanes and floods. The first need in such a situation is to get people to safety, somewhere out of harm's way where they can be fed and where they can sleep. And where they can get information about what is happening, what they can do, and to find out about their loved ones.

Then once the initial crisis recedes, it's about getting peoples lives back on track, a process that can sometimes take months or even years. Many people rely on insurance for this second part. That is going to become harder to find as insurance companies pull back from covering the most likely disasters. And even when it is available, insurance only fixes part of the problem, the money side. For everything else the community needs to rally around.

This is not a recent problem, but it does seem that it's becoming more frequent. And the consequences are becoming more serious. In September 2022, Hurricane Fiona devastated Puerto Rico's electricity grid. Striking landfall just three days before the five-year anniversary of Hurricane Maria that caused the longest blackout in US history, Fiona’s destruction to the grid was a stark reminder that the recovery efforts after Maria were not enough. Since 2017 Puerto Rico has had a hankering for resilient microgrids. This desire is only growing during the post Hurricane Fiona recovery as solar has been a lifeline.

This is a problem right across the Caribbean. Researcher Julien Gargani looked at the impact of major hurricanes on the islands of the region - identifying that after the major hurricanes, electricity energy production showed a slow recovery followed by a stable phase lasting several months, corresponding to c. 75% of the initial electricity production. In other words, recovery was slow, and many communities took long periods to get back to the situation before the hurricane damage occured.

And this is not a new theme. Back in 2012, analysts were writing about how natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina in the U.S., and the earthquake off the coast of Japan in 2011, had profound effects on the electricity grid. In a 2009 report, the U.S. Department of Energy stated that Katrina caused approximately 2.7 million customers to lose power, and that it took four to eight weeks to restore electricity to all but the worst affected households in the Gulf region. While official figures say that the freezing conditions that followed massive power failures in Texas during Hurricane Uri in 2021 caused 151 deaths, a study of state mortality patterns suggested the figure may have been as high as 700.

And it's not just about losing electricity, although that is often the most visible impact. Sources cited by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas estimated the storm-related financial losses across Texas ranged from $80 billion to $130 billion. And a study by the University of Houston, Hobby School of Public Affairs found that three-quarters of respondents had difficulty procuring food and groceries.

This is where resilience hubs can literally be a lifeline.

They can create spaces where people can come to get information, access the internet, charge their phones (and even their cars), get essential food and water, stay warm, and get medical assistance. And, they can also be a centre for emergency services such as fire and ambulance, plus a source of backup electricity, keeping essential services operational.

And they should not just be a place that is shut up until disaster strikes. They can also serve a wider role during non-disaster periods, being a hub for the local residents, based around meeting spaces, community gardens and education services. They could even provide advice on how to prepare for a local disaster. Not the generic advice you get on government web site's, but specific advice, targeting local conditions and risks. Getting local services down to the local level.

Who pays?

The obvious answer is the government. But are they really the right people? Maybe it would be better if the resilience hubs were a public/private/local venture. The government and emergency services contribute part, and insurance companies and other similar financial institutions contribute the rest. With the local community managing the day to day operations.

You may wonder why insurance companies should pay. Its good risk reduction and management. A prepared community could claim less.

And an obvious approach is to make these hubs modular - allowing construction costs to be minimised, and build times to be shortened. They could be build in a factory and shipped out. They sound like a sensible measure for governments, and an interesting investment opportunity.

This blog was previously published as "Building resilient hubs". We have updated and republished it, to include some recent developments, especially around the withdrawal of insurance cover.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.