Yes, we are using lots of coal, but for how long?

We might be using more coal, a move that seems to take us away from our desired end destination. But we caution against interpreting this as meaning that coal, or even in many cases gas, has a positive long-term future from an investing perspective.

Summary: Coal is apparently back. We have seen more and more commentary that suggests the surge in coal use means the switch to renewables is stalling. Just as one swallow doesn't make a summer, the current crisis doesn't mean that coal will make a comeback.

Why this is important: Its easy to get carried away with short terms trends. In this case, a combination of supply chain issues and the impacts on O&G prices from the war in the Ukraine. It's led to a rise in coal use in some countries, but this feels to us like a short term bridge rather than a big theme. But economics will win out in the medium term.

The big theme: While the trend of more solar and wind generation in our electricity supply mix is clear, how quickly we can get there is harder to define. We should never forget that electricity supply is about reliability, resilience and flexibility. Which means that in some cases we might have to make short term decisions, such as using more coal, that seem to take us away from our desired end destination. But we caution against interpreting this as meaning that coal, or even in many cases gas, has a positive long-term future from an investing perspective.

The details

Yes, we are using lots of coal, but for how long?

Summary of a story from The Sydney Morning Herald

The biggest clash between the mining industry and federal government in more than a decade is brewing over a cap on fossil fuel prices after the Australian Energy Regulator confirmed rising coal prices are a key driver of soaring power bills, a claim the miners have fiercely denied. The regulator said higher power prices came about when more coal than usual was bought on the spot market after domestic supply was reduced by wet weather. This meant soaring international coal prices were unusually influential in driving up wholesale prices.

The Minerals Council, whose membership includes coal miners BHP, Glencore and Whitehaven, has said it will wage a multimillion-dollar advertising blitz against price caps on coal, akin to the resource sector’s $22 million campaign in 2010 that was credited with killing off the Rudd government’s proposed resources rent tax. They argued it wasn’t a shortage of coal or high prices internationally that sent prices soaring in June, and blamed mechanical failures at coal plants, pointing out that most coal plants buy their fuel under long-term contracts from mines.

Let's take a look at why this is important...

Why this is important

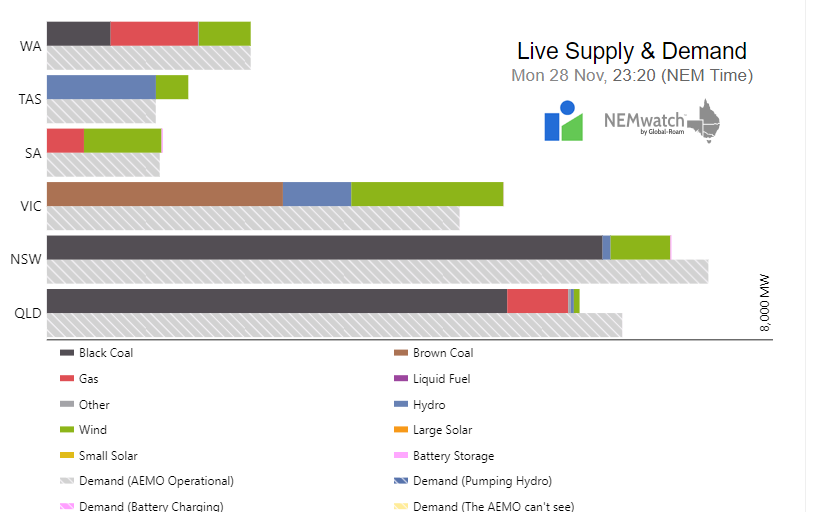

While some Australian states have been leaders in transitioning to renewables, the country as a whole is still a big consumer of coal for electricity generation. Yes, the chart above is from the middle of the night, but coal remains important to Queensland, New South Wales (hard coal in black) and Victoria (brown coal in brown). And it's not just Australia, coal use has recently surged in countries such as China, India, and across the European Union.

First point - it's important to keep this in perspective. Europe is temporarily returning coal units to service to survive Putin’s gas cuts, and China and India are still building new coal power plants. But this misses the big picture. Rich nations have stuck to pledges to phase out coal power. While some countries such as Britain and Germany have delayed the closure of coal plants this winter due to the war in Ukraine and concerns over Russian energy supply, overall phase-out dates remained intact. Plus, in the US, one of the countries least impacted by the current energy crisis, coal use for electricity generation was down 16% in September.

And if you look across the first half of the year, rather than just recent months, global coal use for electricity generation actually fell by 1%. Global electricity demand rose 3%, with wind and solar meeting 77% of this demand growth, and hydro more than meeting the remainder. And, in China, the rise in wind and solar generation met 92% of its electricity demand rise.

Second point - investing is a forward-looking activity. While there are some who expect the current European energy crisis to linger, possibly for years, this is a short period in the context of the life of a typical power plant. In many markets wind and solar are cementing their positions as the cheapest new build technology. Yes, it's possible that we may see the use of coal for electricity generation remain high for a while. But those analysts who see the surge in coal as a failure of renewables, and therefore a portent of the future, are likely to end up missing a trick. Coal still doesn't feel like an asset that investors will want to own for the long term. So, we shouldn't be surprised if the coal industry, as in the Australian case, has decided to try to use the court of public opinion as a way of defending its position.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.