Is gas flaring a solvable problem?

Gas flaring is part of the wider methane emissions challenge. It gets a lot of attention, in part because its highly visible. How easy is it to fix ? Part solutions seem easy, and financially viable, full solutions look tough.

Summary: Gas flaring is part of the wider methane emissions challenge. It gets a lot of attention, in part because its highly visible. How easy is it to fix? Part solutions seem easy and financially viable, full solutions look tough.

Why this is important: One of the toughest challenges around the transitions relates to where is it best to invest - which solutions create both the most impact and are financially viable (or can be made viable). Sometimes fixing the most high profile issues, in this case gas flaring, is not where the big wins are to be found. But these solutions are still worth implementing, every bit helps.

The big theme: We know that we are going to need Oil & Gas for many years, if not decades. Funding low carbon alternatives is the best solution, gradually reducing demand. And for the production we need to keep going, cutting emissions will help reduce the negative impacts.

The details

Gas flaring - part of the wider methane emissions challenge

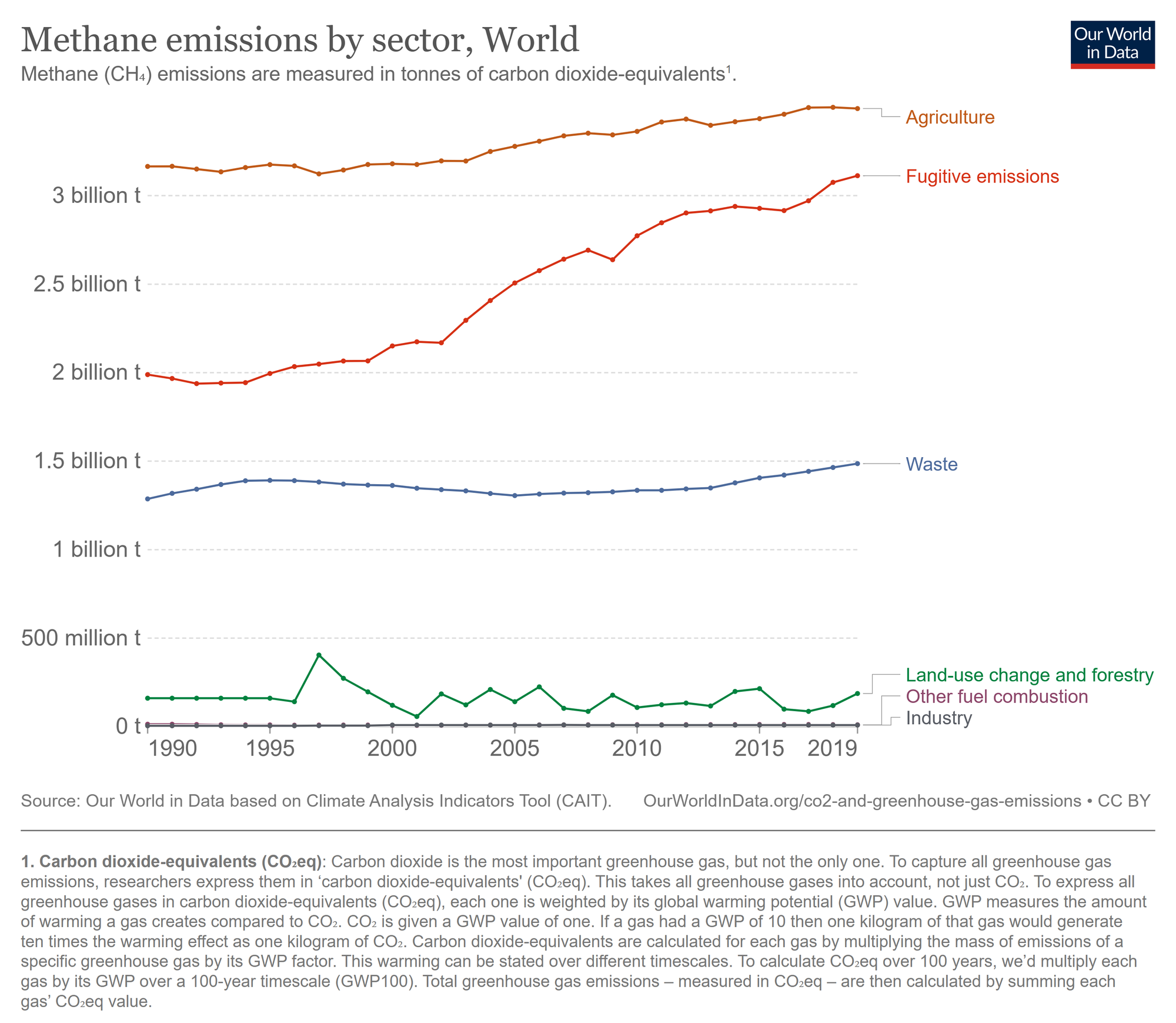

I grew up in New Zealand (very agricultural for those who don't know it), and so I was not surprised to discover that agriculture is still the main contributor to global human related methane emissions. What was more interesting is how quickly "fugitive emissions" from the energy system are catching up. Waste is third, and then all the other sources are rounding error.

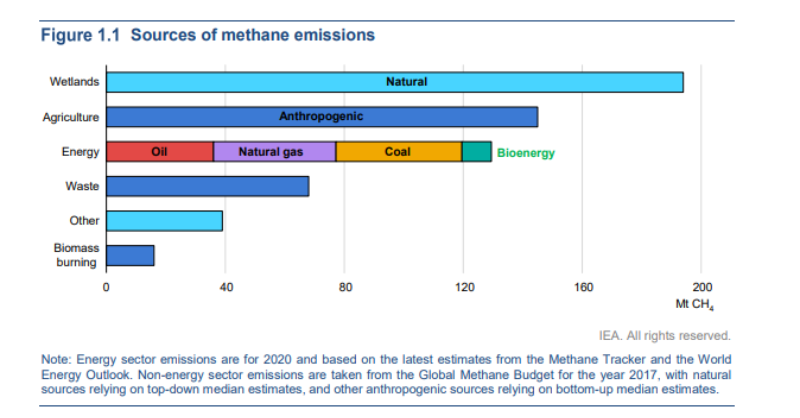

We will come back to agriculture and waste in other blogs, for today its emissions for fossil fuels. But before we do, a quick chart from the IEA that includes natural methane emissions. This gives the debate some context - methane from natural wetlands is also a big deal. Not a topic for today, but don't forget this, we will come back to the topic in a later blog.

How big a deal is gas flaring?

I know we say this a lot - but its important to give these debates some context, relating to both how big a challenge they are, and what we can do to resolve them. Gas flaring gets a lot of publicity - its highly visual, and the burning of the gas seems to many to be a waste of energy. In 2022 the World Bank did a big report, rather boringly titled" Financing Solutions to Reduce Natural Gas Flaring and Methane Emissions". It actually turns out to be more interesting than the title suggests, and a mine of useful information (although you do have to dig).

Key fact - just over half of Oil & Gas scope 1 and 2 emissions come from the flaring of natural gas and the releasing of methane into the atmosphere. But flaring is the smaller of the two.

The emissions from upstream and downstream flaring accounted for 8.6% of scope 1 and scope 2 emissions from oil and gas operations, or c. 462 million tons of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2 e). The release of methane was much larger, representing 46.2% —almost 82 Mt or about 2.5 GtCO2e. So, from a climate perspective methane emissions are materially more of an issue than flaring.

So while reducing flaring is important, it comes a way down the list of actions that really make a difference. It doesn't mean we shouldn't reduce it, but we need to keep the gains in context.

What exactly is flaring, and why does it happen? Flaring is the controlled burning of gas during oil and gas operations. Sometimes its a safety issue, for instance to reduce well pressure. But it also happens when the facility lacks the capacity to reinject it back into the well, use it on site or dispatch it to market.

The Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership (GGFR) estimates that the total volume of natural gas flared globally in 2020 was 152 billion cubic meters (bcm), of which upstream flaring accounted for 91% and mid/downstream for 9%. To give this context (that phrase again) global gas production is c. 4,000 bcm. So, just under 4% is flared off.

As the World Bank report highlights:

"Hypothetically, if all the gas flared could be used for electricity production, it would be sufficient to generate over 700 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity, enough to power the entire African continent.12 Valued at a wholesale price of US$2.00 per million British thermal unit, the gas flared in 2019 would be worth about US$10.6 billion and that in 2020 worth about US$10.0 billion. "

The key word here is hypothetically. There are alternative uses for the gas, but in many cases they need a minimum amount of gas being flared to make them economic (without financial support).

So what are the practical alternatives to flaring? The already mature technologies include its use in a gas fired power station to provide electricity to the site (gas to power), reinjection back into the oil reservoir, and conversion to Liquified Petroleum Gas (LPG), Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) or Compressed Natural gas (CNG). The converted gas is then shipped ashore and marketed.

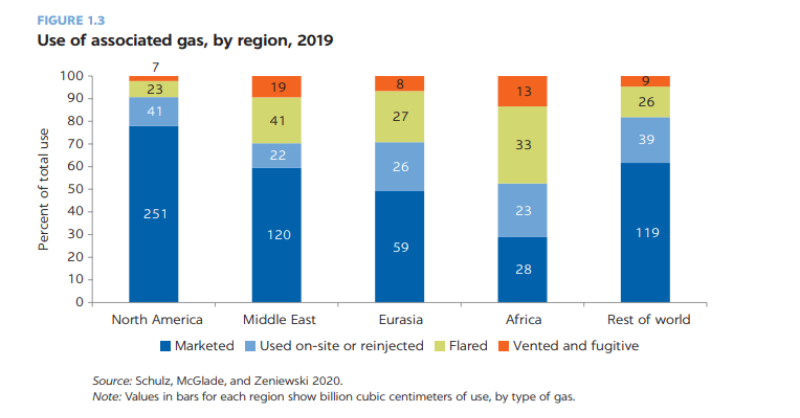

What happens now? It depends on where the production well is located. Most gas in North America is marketed (78%) , and only a small percentage is flared (c. 9%). By contrast, in Africa c. 47% of the gas is either flared or vented.

Are the barriers to solution roll out financial?

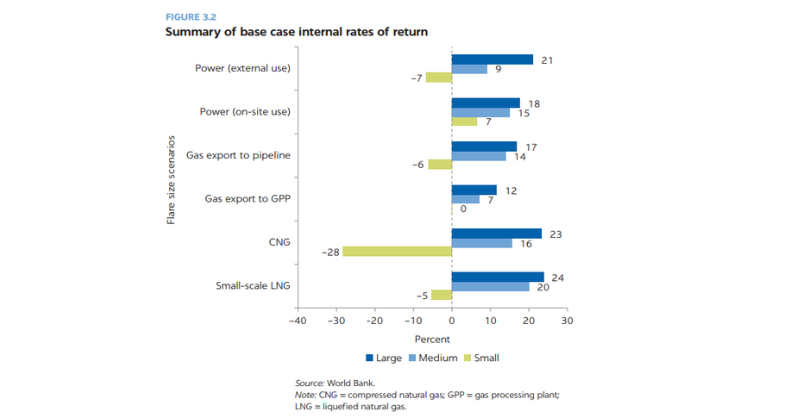

Not really. According to the World Bank analysis, while many smaller projects (below 5 million standard cubic feet per day or mmscf/d) do not have attractive financials, above this level the investment stacks up. At 10 mmscf/d the project IRR's would typically range from 12% up to 24%. So well over the likely cost of capital.

So why is this not happening already. Projects in the range 5-10 mmscf/d, where a feed into a convenient existing gas pipeline does not exist, require a capital investment of c. $30m to $60m (gas-to-power for external use, with an output ranging from 17-38MW).

Projects of this nature do not meet the requirements of traditional nonrecourse project finance, at least in the development phase. Some of the risks include uncertainty about the availability of gas (record keeping on flaring is often poor), off taker risk (who buys the electricity or gas produced and at what price), and of course political risk.

Despite all of this, there are good reasons to believe that a significant proportion of the gas currently being flared can be used, either onsite or for offsite sale as gas or electricity. There are a number of companies that already offer the technology -most approaches are already mature, with limited technology risk. So, the challenge is to put in place the structures needed to make it happen. This could be a very worthwhile project for either impact investors and/or multilateral agencies.

In a future long blog we shall examine the various solutions to the wider methane emissions challenge, including in agriculture, waste and O&G.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.