Healthy soil elsewhere drives our economy.

Europe relies on the world for it's imported low value agricultural raw materials. Which means that our way of life is supported by soil health, not just within our own region, but globally.

Summary: Europe relies on the world to supply a material proportion of its low value raw materials. We turn these materials into food for ourselves, and into exports of higher-value processed products. This means that our way of life is supported by soil health, not just within our own region, but globally. And the fact that global soil health is declining, is something we should all care about - preferably before we reach the negative tipping point.

Why this is important: Soil is a complex system that is critical to food production, and a key to sustainability through it's support of important societal and ecosystem services. A foundation of soil health is the recognition that managing nutrient availability alone, such as through the use of agrochemicals (mainly fertilizers), is not sufficient for optimizing plant growth. There is now an increased recognition that some management practices used in intensive agriculture to increase total plant production are actually detrimental to soil health.

The big theme: The impacts of climate change are increasing in frequency and intensity around the world, particularly life-threatening heatwaves, floods, storms, and droughts - leading to further and longer-term impacts such as food insecurity, entrenched poverty, and economic losses. Climate change has already reduced global agricultural productivity growth by 21% since 1961, and by up to 34% in Africa

Soil health is essential to the modern economy. It's not only the foundation for our agricultural production, it also a material contributor to water quality, climate change and human health. Plus, it's not just about feeding the world, as important as that is. Healthy soils are also a major contributor to economic activity and employment. Those interconnections are becoming increasingly strained, which is why financial professionals should care about healthy soils. To misquote the title of a recent film, 'don't look up, look down'.

The Detail

Summary of a study published by WWF: Systemic Change is Key to European Food Security and Resilience

- Claims that the EU is ‘feeding the world’ with its agricultural exports are no longer tenable. In fact, in many respects the EU ‘eats the world’. Despite being the world’s largest exporter of agri-food products in economic terms, the EU carries a significant trade deficit in nutritional terms. The EU’s agri-food trade model revolves around importing low value raw products, such as cocoa, fruits and soybeans, and exporting high-value ones – making a positive contribution to the EU economy, but not necessarily to the global food supply, resilience, or food security. Given this, the current mantra that to solve the food security crisis that ‘we must produce more in Europe to feed the world’ is not responding to the reality of the situation. It fails to recognise that Europe depends on the world for its food.

Why this is important

In previous blogs on our Agricultural and Natural Capital systems we have looked at water (scarcity) and the over use of fertilisers and pesticides.

For this Quick Insight we want to go 'deeper' (or 'look down' if you prefer) to examine the challenges posed by the degradation of our soil. As a recent Natural History Museum blog stated:

"the dirt beneath our feet often goes unnoticed but it is key to sustaining all life on Earth".

- Soil is not an inert medium but it's a living ecosystem that is essential to life. It takes hundreds and thousands of years to form an inch of topsoil, and many more centuries before it is fertile. The soil we rely on to grow our crops and feed our animals is hard and slow to replace. It makes a lot more sense to preserve and protect what we have.

- In the last few decades, soil degradation has been sped up by intensive farming practices like deforestation, overgrazing, intensive cultivation, forest fires and the spread of monocultures. These actions disturb or damage the soil and leave it vulnerable to wind and water erosion.

This is not a new issue.

- We have known about it for many years, but it's now (correctly) getting a lot more attention. In part it's because of recent disruptions to our agricultural supply chains, which have exposed the inherent weaknesses in how we grow our food. But, it's also about the future. Unless we can find ways of materially reducing food waste, we will need to grow more, a lot more.

The FAO estimates that by 2050, agriculture will need to produce almost 50% more food, fibre and biofuel than in 2012. Agricultural production in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa will need to more than double just to meet estimated calorific requirements. The rest of the world will need to produce at least 30 percent more. Achieving this will mean increasing crop yields and cropping intensities as well as diversifying crop varieties. And many of these choices will have negative impacts on soil health.

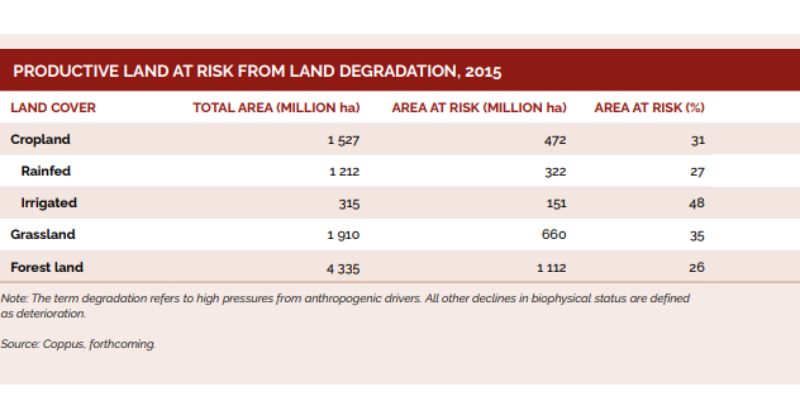

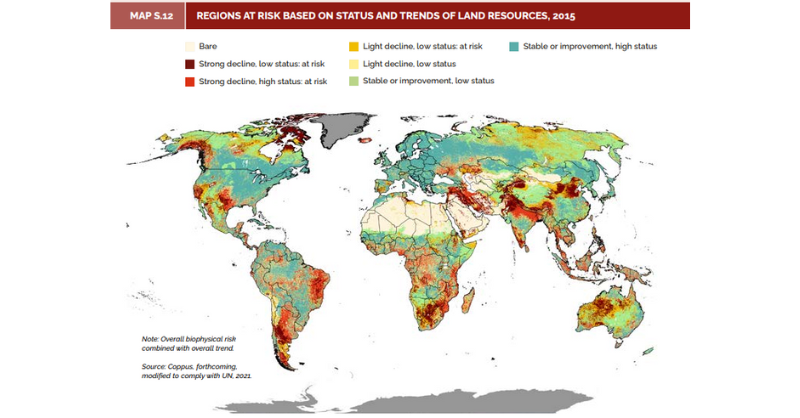

And while there are challenges in all regions, the biggest risks are concentrated in specific regions such as the western states of the US, parts of the Middle East, Southern Africa and the northern Indian subcontinent. The regions most at risk are those indicated in the chart below by the darker colour's, especially those shown in red (' a strong decline with currently a high productive status').

Who's problem is it?

- At this point in the discussion we often hear finance people say ... 'well yes, I understand all of this, but I think this is something that is best handled by the aid agencies'. The unspoken implication is that this is not something that directly affects them. Let's park for a moment the fact that one region that is becoming increasingly stressed and degraded is the South West of the US, and examine the exposure of Europe to the global food markets.

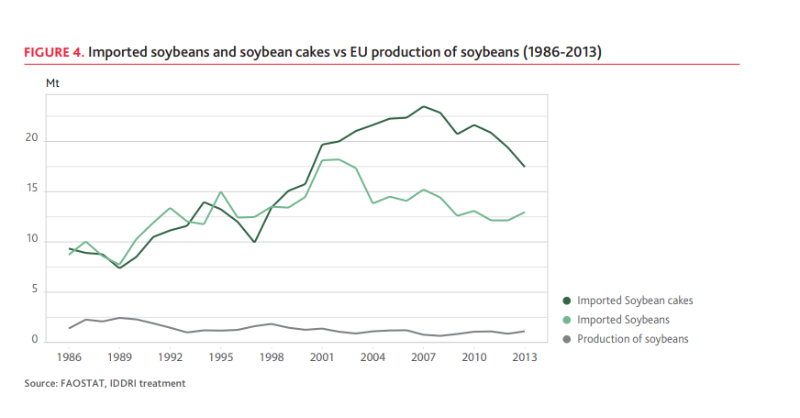

- The region is a net importer of both calories and proteins, relying on imports for the equivalent of 11% of the calories consumed and 26% of proteins. And despite what we may have thought, this is not a recent issue. In fact it dates back to the late 1990's and early 2000's. Among the important imports are soybeans and soybean cake - mostly for animal feed. Note - the line right at the bottom is European domestic production of soybeans. Most of the world's production of Soybean's comes from Brazil (global No 1) and the US. So, we have to consider to what extent the region has exported deforestation to South America ?

- And looking at the export side, of the top-10 exported agricultural products, contributing 44% of total exported value, most are ‘premium commodities’ (e.g., spirits, wine, cheese, chocolate, and other highly processed food commodities) which are bought by consumers in countries such as Japan, USA, and China.

- Hopefully by now it's becoming clear that long-term food security and resilience in Europe depends on tackling the climate and biodiversity crisis around the world. We need to move the debate on from 'if we don't produce more food we will starve' to 'where should we best source our food from, and how do we ensure that it's produced in a sustainable manner'. And by sustainable, we don't just mean in terms of it's impact on deforestation and local communities. We mean in a manner that can be continued well into the future. This requires healthy soils.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.