Green cement - there are solutions

The production of concrete, or more accurately cement, accounts for between 5-8% of global GHG emissions. This is a similar scale to the GHG emissions of passenger cars. There are solutions - and not all revolve around new technologies.

Summary: The production of concrete, or more accurately cement, accounts for between 5-8% of global GHG emissions. This is a similar scale to the GHG emissions of passenger cars - but it gets a lot less attention. We think this needs to change, especially as increasing urbanisation will mean we are likely to use more concrete in the future, not less.

Why this is important: Unlike passenger cars, where we have a financially and technically viable alternative (electric vehicles or EV's), the current low carbon alternatives to traditional cement are niche products, and they look hard to scale. We will need a lot of work, and investment, over the coming decade or more if we are to get close to decarbonising this important industry. And we need to start now.

The big theme: The so-called hard to decarbonise sectors, steel, cement, chemicals, and some forms of transport, are currently massive contributors to GHG emissions and environmental (& social) harm. Yes, we need to focus on green electricity, and EV's, but we also need to start tackling the harder challenges - which means investment and financial support.

The Detail

Summary of a study to be published in Resources, Conservation & Recycling

- This paper is currently only in prepublication format, but its still worth highlighting, partly as it's written by some leadign figures in the industry. These include Chris Cheeseman from Imperial College London. Their study examined various solutions that offer the potential to reduce the GHG emissions from cement production. These included clinker substitution, use of alternative fuels, improved kiln efficiency, and carbon capture and storage.

- Their conclusion is that together (our emphasis) there is the potential to reduce emissions by up to 88%. Good, but not 100% ie net zero. But, to be fair, there are other techniques, mostly around building design and concrete production, that could add to this figure.

Why this is important

This blog is an expanded version of our recent free blog, with more detail on the potential solutions, so that we can start to act.

Concrete is the most widely used man-made material, commonly used in buildings, roads, bridges and industrial plants. And it's the second most used resource, only after water. It's hard to imagine much of our world without it. And our best estimate is that we are going to be using a lot more of it in the future.

- But producing the cement needed to make concrete already accounts for 5-8% of all global greenhouse (GHG) emissions. That is very similar in scale to the GHG emissions from passenger cars (c. 7.1%).

- Let’s pause a minute here…. making concrete generates as much GHG emissions as all of the world's passenger cars put together. How much attention does reducing passenger car emissions get? Pretty much every day we see a major story in the press or online about Electric Vehicles. But how often do you read about concrete?

- One reason is that concrete is almost invisible. It's almost everywhere, but in a way that means it slides into the background. It's not as obvious to the general population as cars are. But the other reason is that decarbonising concrete is tough. Not impossible, but really hard to do in a financially viable way. And so we don’t have an Elon Musk (of Tesla fame) launching a new concrete, - forcing the incumbents to take action.

The three main questions we need to be able to answer

- There are three main questions we think people who care about sustainability need to be able to answer about concrete/cement production.

- Why does it produce so much CO2?

- Is there a better way of producing it that produces less GHG emissions? and

- Is there an alternative material that does the same job but better?

- And for questions 2 and 3, it's not enough to say, this solution works on a technical basis. It also needs to be financially viable. If the alternatives end up being more expensive, then we are going to need subsidies, and probably very large ones.

Newly industrialising countries use a lot of cement

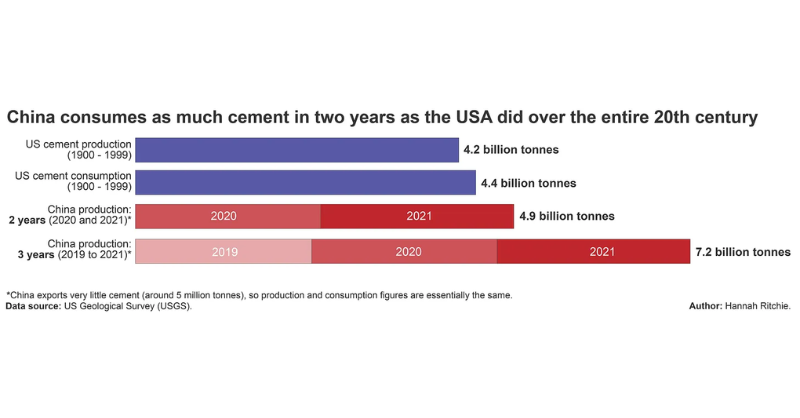

- And one last thing before we move on. Since 1985, China has become the largest producer of cement and they consumed more cement in 2 years (2020 to 2021) than the U.S. consumed in the entire 20th century. In 2018, China’s cement production accounted for ~56% of global cement production. This is all from fact checker extraordinaire Hannah Richie.

- Now, this is not because China uses cement for anything unusual. It's just because it's industrialising so quickly. And if other countries follow a similar route, then we could see the world using a lot more cement, even if the rate of growth in China starts to slow.

How do we currently make cement?

- When you think about it, concrete is pretty amazing. You mix gravel (aggregate) with sand, some grey powder (cement) and a bit of water and hey, you get something that is pourable, can take up almost any shape, and yet once it sets, it's very hard and strong. And it's the chemical properties of cement that make this happen. But sadly, it's this same cement that makes up nearly all of the GHG emissions produced in making concrete.

- We will park for now the environmental impacts of gravel extraction, and what happens at the end of a building's life, and focus today on how we make cement and why it generates so much GHG emissions.

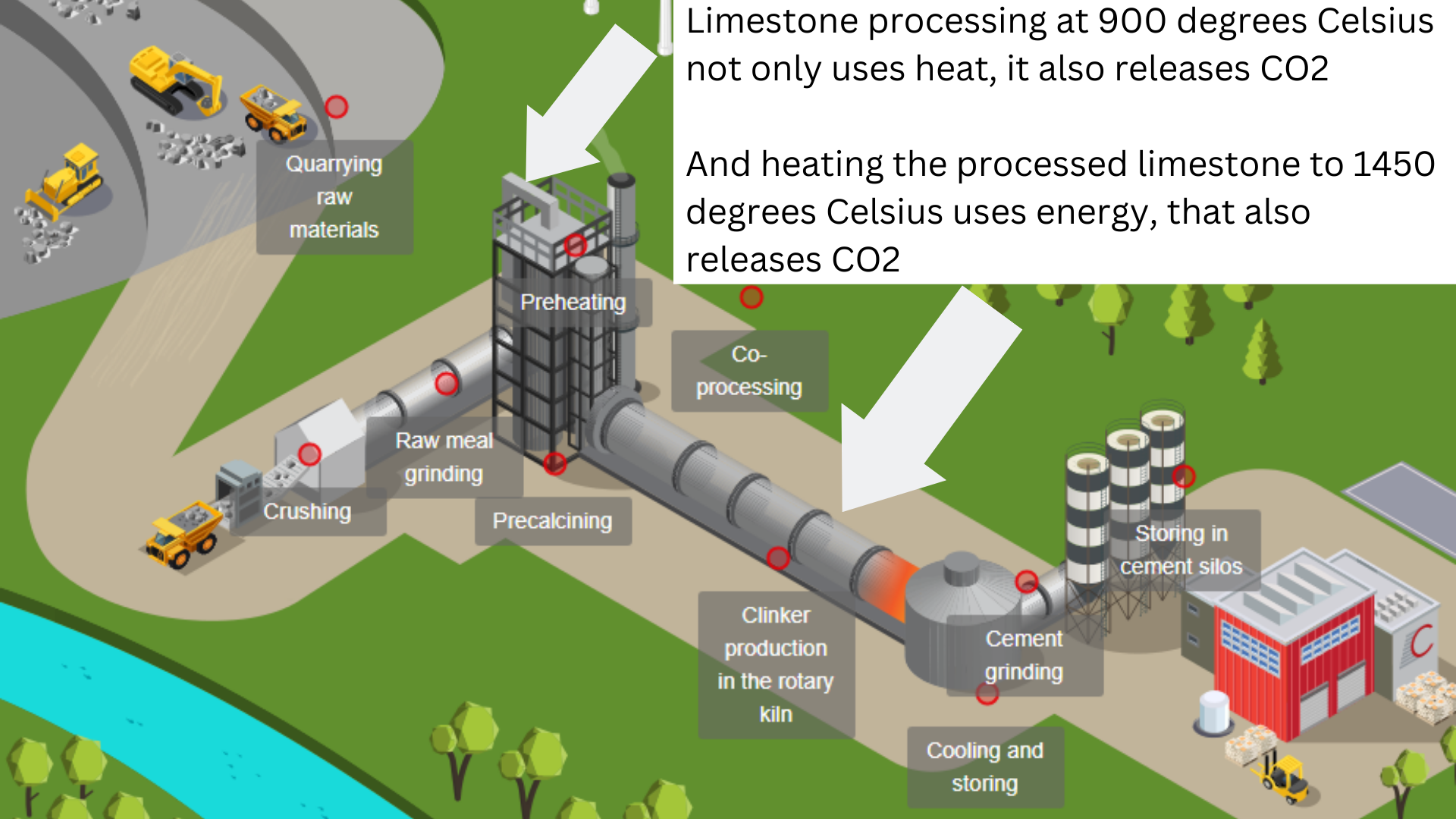

- It's actually a fairly simple process. We quarry limestone, crush it, and then it's “calcinated” at around 900 degrees Celsius to create lime. This is then heated to 1,450-1,500 degrees Celsius, in a rotary kiln, to create what is known as clinker. Finally, the clinker is ground to create cement.

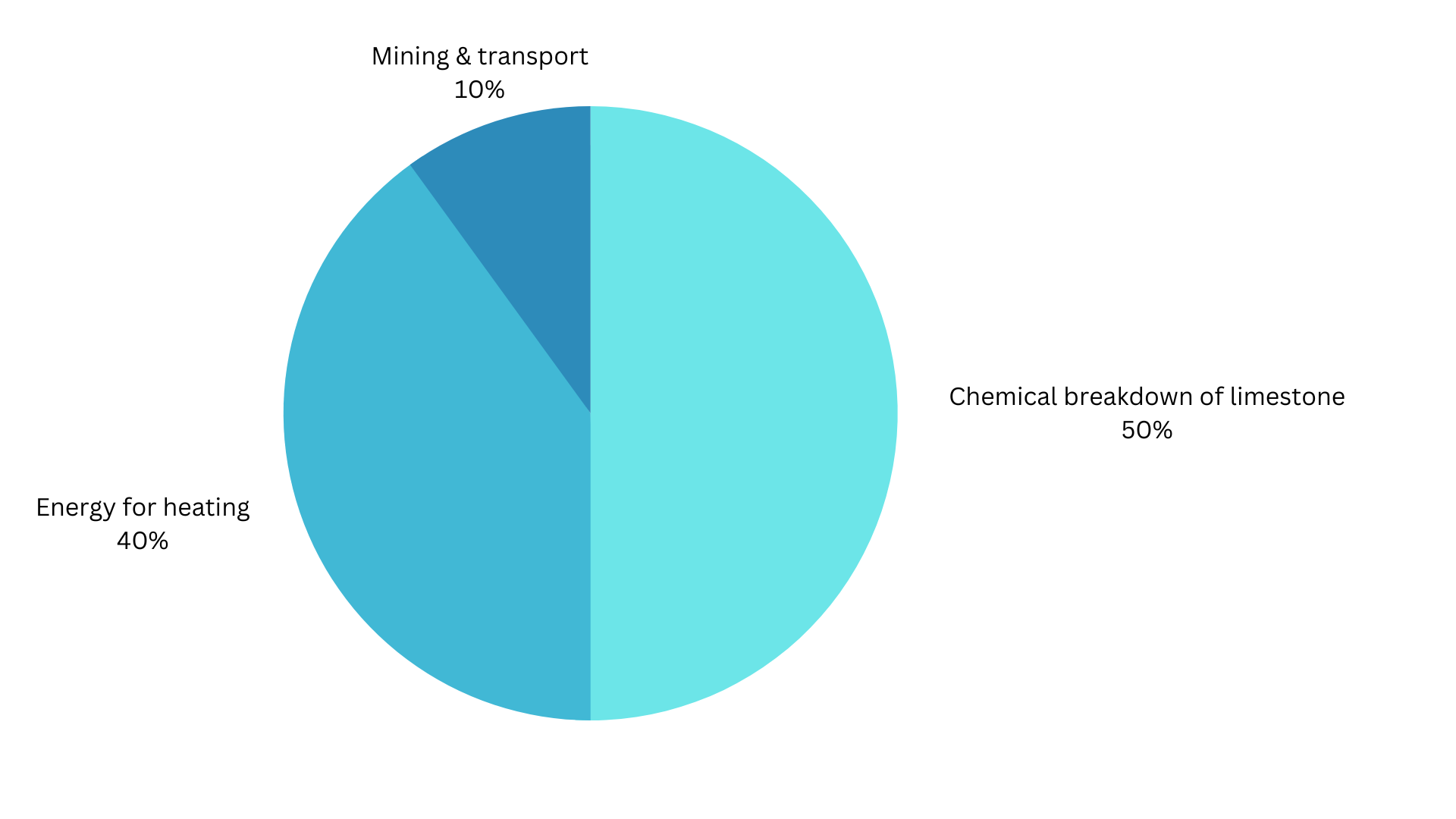

- So where do the GHG emissions come from? Typically, just over half come from the chemical reaction as the limestone is turned into lime. A further 40% come from burning fossil fuels to heat the kilns to the temperatures needed. And the last 10% of emissions come from fuels needed to mine and transport the raw materials.

- This gives us a bit of a clue as to why decarbonising cement production is so tough. The first challenge is that the chemical process that releases the CO2 is an inherent part of turning limestone into cement. The production process just doesn't happen without this stage. To reduce these emissions we need to use something else other than limestone as a raw material, which is tough.

- The second challenge is the high temperatures needed, up to 1,500 degrees Celsius. It's possible to electrify this, but the technologies to do this consistently are still in development. We can also use alternatives such as biomass or waste as an energy source - but supplies are limited and a lot of other decarbonisation technologies also want to use the same raw materials. And in some markets, such as Europe, around 43% of fuel consumption already comes from alternatives, so scaling this up further is difficult.

So what can we do?

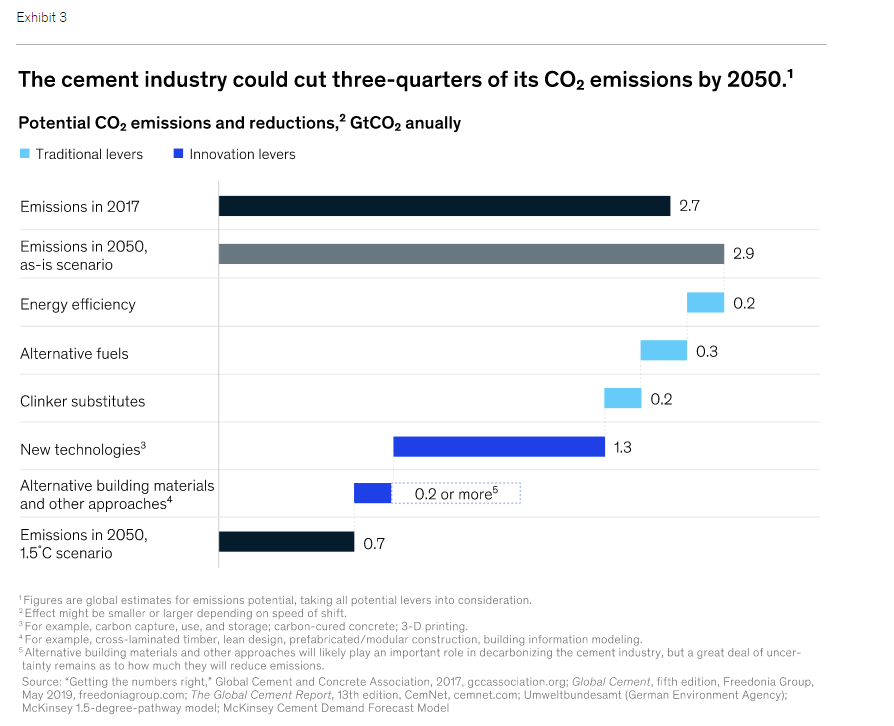

- It's important to be clear, there isn't a single simple silver bullet to this challenge. And unlike say Oil & Gas, its hard to see a future where we don't continue to use a lot of concrete, and hence cement. So how does the jigsaw fit together. Back in 2020 McKinsey is a study, looking at the potential contribution of the various solutions they had identified.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, they saw new technologies as being the biggest contributor. But is this right, is it only a technology issue, or can we make big changes by other, less dramatic (and perhaps "boring") approaches? We think we can.

There have been many reports written on this, but the one I like, for its detail and its realism, is one from the Institute of Civil Engineers (just as an aside, their standards are such that even with my experience, I was unable to be accredited, as an engineer, by them !).They have seven actions that they see as essential if we are to get cement to net zero by 2050. Note that these exclude the use of alternatives to fossil fuels as an energy source.

- Reporting & benchmarking - to assist clients in knowing what products are actually low carbon, and what are not. Plus to encourage innovation. But this is only the beginning, reporting on its own is nowhere near enough.

- Knowledge transfer - this sounds obvious, but research has shown that especially in rapidly industrialising countries, most concrete is produced at small scale, by people with limited technical knowledge.

- Better design - we can use less cement, but we need to start with the product design stage.

- Supply & procurement - if clients don't specify low carbon concrete, we will not scale up fast enough. And from here we start to get into the technology solutions.

- Optimising's existing solutions - such as the use of fly ash and Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS), and ...

- Adapt new (known) material technologies - such as the use of cementitious clay materials, known as Supplementary Cementing Materials (SCM) as replacements for the limestone in traditional Portland Cement.

- And finally Carbon Capture - this is probably the most controversial technology, in part because its associated in many peoples minds with efforts to keep using fossil fuels. But remember, the challenge in making traditional Portland Cement isn't using fossil fuels as a heating source, its the CO2 that is emitted as part of the chemical reaction as the limestone is broken down. This technology is still at a pilot stage, but we need to have an informed debate about its long term role.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.