The global response to AMR (not enough)

Antimicrobial resistance is acknowledged globally as a significant macro threat. But how effective are national action plans?

Summary: Researchers have found substantial variability in the strategic responses to antimicrobial resistance (AMR) from governments across the globe. The conclusion is that the international response is currently not enough given the severity and scale of AMR. National Action Plans (NAPs) were particularly lacking in education, accountability and feedback mechanisms which can improve policy direction and implementation over time.

Why this is important: Low Income, Middle Income Countries (LIMIC) are disproportionately impacted by AMR and may not have enough funding without support from foreign donors, philanthropies and other blended finance. Health equity is mentioned more frequently in NAPs from LIMIC and less in higher-income regions even though they have the capability to increase access to medicines in those LIMIC regions.

The big theme: Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) is a macro threat to the sustainability of the human race and other species. It is of a similar level to that of the worst impacts of climate change or biodiversity loss and is inextricably linked. Bringing together biological, behavioural, and physical solutions with appropriately incentivising funding we should be able to continue to enjoy the benefits of our microbe partners whilst avoiding their darker side. This is potentially a massive, if complex, theme for those who care about sustainability; the potential goes well beyond the pharmaceutical industry.

The details

Summary of a research paper from The Lancet

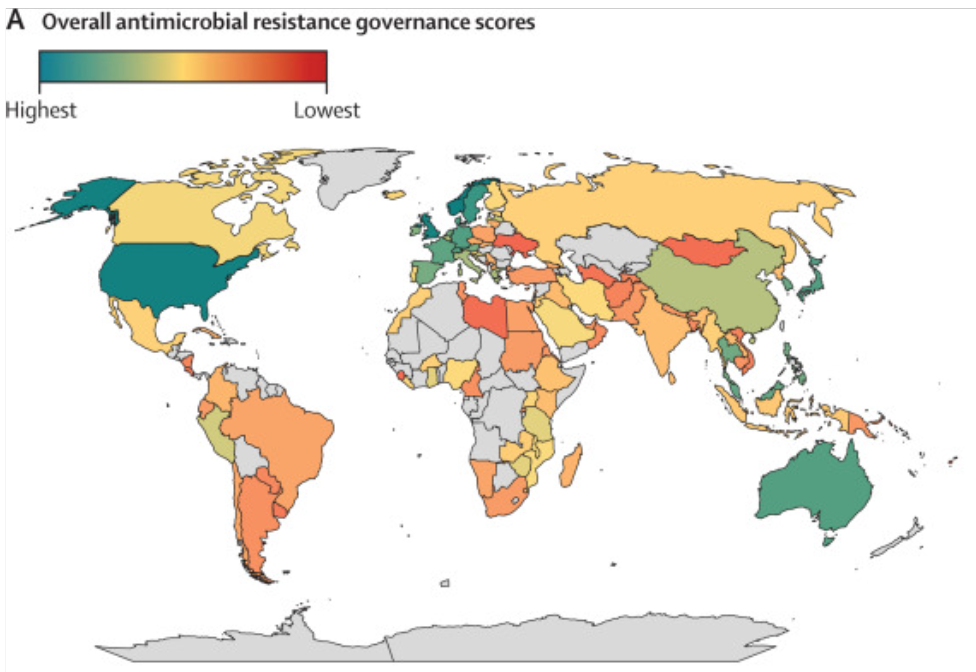

Researchers from the Global Health Governance Programme at the University of Edinburgh reviewed the contents of NAPs from 114 countries looking at policy design, implementation tools and monitoring and evaluation. The NAPs reviewed were those included in the WHO Tripartite Antimicrobial Resistance Country Self-Assessment Survey (TrACSS) 2020-2021.

The highest scoring area was participation (was there substantial stakeholder participation during the development of the NAP?) with the lowest scoring areas accountability and feedback mechanisms. Of the 20 countries with the highest overall governance scores, 17 were high-income countries and 11 were from the European region. Most of the lowest scoring 20 countries were upper-middle-income countries and lower-middle-income countries. Seven were island countries. Although 148 countries have developed a NAP as at October 2021 (the date of the study), 33 of those were not in the public domain.

Why this is important

Antibiotics and other antisepsis measures revolutionised surgery and healthcare. Highly invasive operations, such as gut surgery and joint replacements all depend on antibiotics to prevent infection and be successful. Certain treatments which render the immune system less effective, such as chemotherapy, are made viable by the support provided by antibiotics. Where previously catching certain infections was pretty much a death sentence, antibiotics and other antimicrobials provided hope. However, some microbes have developed resistance to those antimicrobials posing a threat.

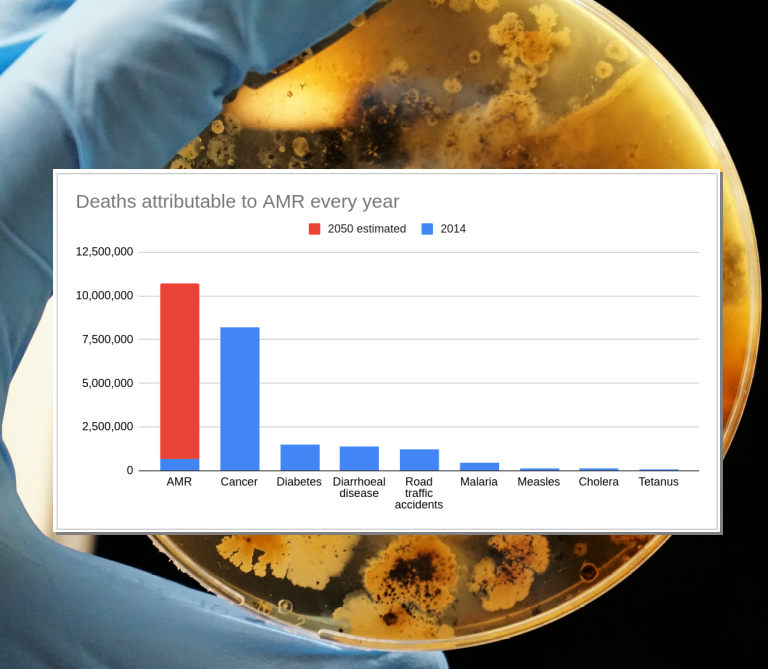

A landmark 2016 report “Tackling drug-resistant infections globally,” a review of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) chaired by Jim O’Neill, estimated that 700,000 deaths per year were due to AMR. The report forecast that figure reaching 10 million by 2050, costing the global economy more than US$100 trillion and pushing millions of people into extreme poverty. A study estimating the AMR burden in 2019 published in January 2022 in The Lancet found that 1.2 million deaths were attributable to bacterial AMR globally. That means that AMR is the leading cause of death, higher than HIV/AIDS (~up to 860,000) or malaria (627,000). The study’s co-author Professor Chris Murray from the University of Washington commenting on the O’Neill report estimate of 10 million deaths per annum by 2050 said that “...we now know for certain that we are already far closer to that figure than we thought.” Low Income and Middle Income Countries (LIMIC) are disproportionately impacted. Children in sub-Saharan Africa are more than 14x more likely to die before the age of 5 than children in high income countries.

If at the high level we are “running out of antibiotics that work” the natural focus would be to “find more antibiotics.” That is a rational thought and a valid approach. It is however only one avenue - pharmacological. We can also look at ways to reduce the chance for microbes to develop resistance by reducing the need to use them in the first place. There are behavioural changes including improving hygiene at personal and corporate levels and potentially changing how people interact to reduce the risk of spreading infection. Plus, using antimicrobials only for the appropriate infection, and reducing waste antimicrobials from entering water systems. Through our understanding of the way in which microbes interact with us, there may be ways to disrupt them physically and stop them being pathogenic, for example stopping them forming biofilms. Finally, as with any innovation that requires transition, the right financial and political incentives need to be in place. Results from the study showed that countries' intentions about coordinating their national response to AMR were mainly focused on designing and implementing policies but there was little effort on systematic review and feedback to improve strategic policy and implementation. Efforts are interdependent and so, as the authors point out "countries should aim to improve activities relevant to all areas and should avoid disproportionately prioritising resources in one area and neglecting others."

As highlighted above, LIMIC are disproportionately impacted by AMR and may not have enough funding without support from foreign donors, philanthropies and other blended finance. As highlighted in the study, health equity is mentioned more frequently in NAPs from LIMIC and less in higher-income regions even though they have the capability to increase access to medicines in those LIMIC regions. As sustainability efforts increase we are seeing increased focus and implementation of health access programmes from pharmaceutical and healthcare corporates. This is an area we shall be writing on in the coming weeks.

The study is an important first step although has some limitations. TrACSS responses are generated by self-assessment survey and are not independently verified so there could be an overestimating of strengths or under-reporting of weaknesses. AMR specialist and champion, Dr John Rex points out though that with the study's level of comparability between National Action Plans we can "move beyond simply counting the number of published NAPs to assessing areas for improvement and global cooperation."

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.