What investors can do to improve our soil (and why)

Investors need to care about the state of our soil. It's not a problem taking place 'over there'. It impacts us directly, via the food we grow on the soils in our home region, and indirectly, through the food we import. Impacting the supply chains of all companies in the food industry.

Summary: Investors need to care about the state of our soil globally. It's not a problem just taking place 'over there'. It impacts us directly, via the food we grow on the soils in our home region, and indirectly, through the food we import. Impacting the supply chains of all companies in the food industry. But it can feel like an almost intractable problem. The good news is that solutions are known, we just need to find ways of implementing them. Fortunately, finance-based innovation is something we are good at.

Why this is important: The experiences of the last year or so, the surge in food prices, and more recently ongoing shortages, have been a wake up call. Food security isn't about 'can we get the food we want cheaply?' It's more about 'where will our food reliably come from in five, ten and twenty years time?' Companies need to start building resilient supply chains, that can cope with the food production volatility that is our new normal.

The big theme: The impacts of climate change are increasing in frequency and intensity around the world, particularly life-threatening heatwaves, floods, storms, and droughts - leading to further and longer-term impacts such as food insecurity, entrenched poverty, and economic losses. Climate change has already reduced global agricultural productivity growth by 21% since 1961, and by up to 34% in Africa.

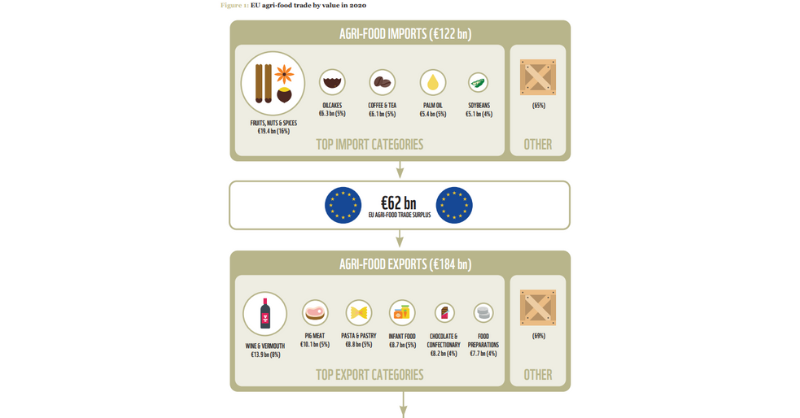

In a recent Quick Insight, we looked at how Europe is exposed to the global soil degradation issue through the food it imports to eat, and the raw materials it buys to process and export.

For this blog we consider why investors should care about the state of our soils globally, and what they can do to contribute to the solutions. This should help inform not just investing decisions, but also engagement. Because this is a challenge that needs informed and focused engagement. The good news is that the technology to fix this challenge is already well understood - our role is to assist in its roll out at scale. Why would we want to do this? Because it makes good sense from a long-term value perspective. Sustainable supply chains can create financial value.

This started off being a blog about the actions that farmers can take, but in researching the topic, I understood that there is an important step before this - what can investors do that encourages companies to support the farmers who want to change? The original blog, on what farmers can do, will come soon.

The Detail

Why agriculture is a sustainability issue

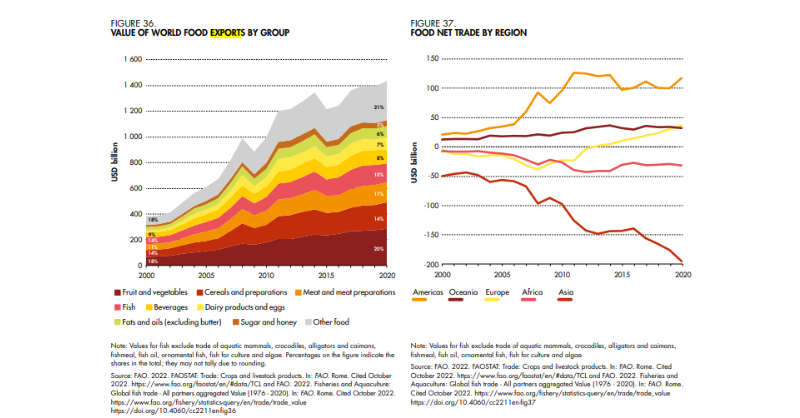

The market for food is a global one. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) the monetary value of food exports globally reached US$1.4 trillion in 2020. Fruit and vegetables accounted for 20% of the total, followed by cereals and preparations (14%). Fish and meat each were 10–11%.

But, as we know from the analysis in our recent Quick Insight, this data only tells part of the story. The FAO has Europe as the world's second largest food exporting region, after the US. But from the WWF report, we know that the region is actually a net importer of both calories and proteins, relying on imports for the equivalent of 11% of the calories consumed and 26% of proteins. The reason for the difference? Many of the regions exports come in as raw materials and go out as value-added food products.

Food production relies on our environment

It might seem an obvious thing to say, but how much food we can produce depends on two natural resources: soil and water. If we get both right then we can sustain or even improve food yields. If we get it wrong, for example by allowing our soils to continue to degrade, then it remains unclear how long we can sustain even the current level of production.

The FAO estimates that one third of world soils are degraded and are losing health and fertility and, based on current trends, this could reach 90% by 2050. The situation with regard to water is no better.

Link 👇🏾

Our food system is global

Our food system is global, and many of us rely on food imports, either for our direct consumption, or economically via reprocessing and export. These imports can only be sustained if the soil (and water) health in the main food producing countries can be enhanced and improved. Maintaining the status quo will lead to further soil depletion and degradation, putting food production at risk.

In many countries farmers effectively live a subsistence life - eating what they grow. This leaves them very exposed to the impacts of climate change on agriculture. To break this cycle they need the skills and tools to reform their farming practices.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2022 Assessment Report warns that:

" climate change and related biodiversity loss ‘have affected the productivity of all agricultural and fishery sectors, with negative consequences for food security and livelihoods’.

What investors can do

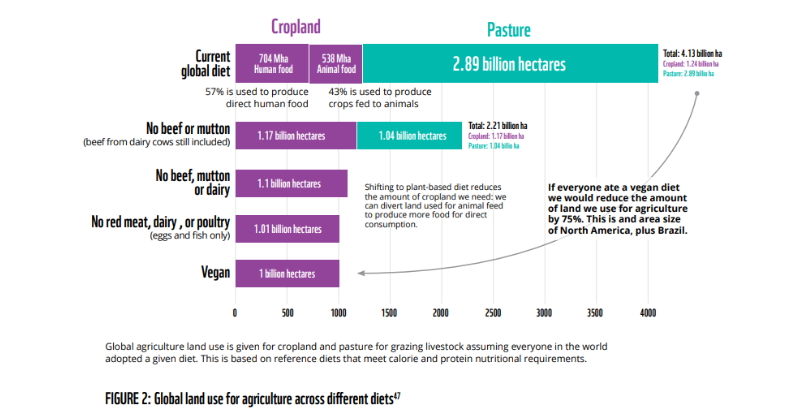

There are two types of solutions that have been proposed. One involves us changing our diets, eating less meat and eating more plant based foods. The other seeks to change our farming practices to enhance, rather than degrade, soil health. These are not either/or solutions. It's likely we will end up with a mix of the two.

Changing our diets is not the topic of this Perspective, but it is helpful to highlight just how much difference this shift could make to the land area used for agriculture. The WWF report estimates that cutting out meat altogether could reduce the total agricultural hectares from 4.13 billion down to 1 billion. Clearly this is simplistic, but it does show the scale of land use required for raising livestock!

Many food companies are expanding their plant-based offering. Yes, there are challenges, but the longer-term trend seems certain. But, it's unlikely that this will be a rapid change. Which means that companies in the food industry and their investors need to investigate changing our agricultural practices.

Changing our agricultural practices

The good news is that we know what we need to change. The bad news is that we have known this for many years, and change has not happened. We expect that if we keep trying the processes that have not really worked in the past, then we should expect the same outcome - we need to try something different.

Insanity Is Doing the Same Thing Over and Over Again and Expecting Different Results - attributed to Albert Einstein (and others)

What might this different approach look like?

The changes needed look simple. It's getting them to happen on the ground that is complicated. We think there are three main groups of actions:

The first group of actions is about changing how we grow crops and manage livestock. These include:

- Greater use of crop rotations (and less monoculture)

- Greater use of cover crops (to avoid leaving the soil exposed to erosion)

- Increasing the re-use of crop residues (including biochar)

- Adaption of silvopasture techniques (trees in pasture land)

- Increasing the use of legumes to better fix natural nitrogen

- Reduced tillage and avoiding the use of heavy machinery on sensitive soils (compaction is bad for soil health).

The second group of actions cover what we grow. This is about greater diversity in our plantings. We wrote about this in a recent blog 'Why investors should care about biodiversity', which highlighted a recent report prepared for the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF). 👇🏾

We can change our impact on the environment through food redesign - using different raw ingredients. Food redesign changes using lower impact ingredients are fairly straightforward: the food manufacturer switches to a similar ingredient, but the end product is still similar. Another, slightly more complicated, way that food manufacturing companies can positively contribute to reversing or at least reducing biodiversity loss is to use more diverse ingredients.

This approach can also enhance the resilience of the food system against threats such as pests, disease, and environmental shocks, and, as a result, enhance food security. 👇🏾

The third group of actions are about using less fertiliser and pesticides. We wrote about this in a recent blog on reducing fertiliser use, and the alternatives that exist. The keys points here are consider 'ecological intensification processes' first (there is more detail in the blog on what this is) and the four R's in fertiliser use (right source, right rate, right time, and right place). 👇🏾

Why not just focus on the farmer?

Our starting point is the understanding that the people we want to make the greatest change, the farmers, are the ones with most to lose and the least to gain. They are financially the weakest link in the food supply chain. If they try new farming practices, and they don't work, they could end up losing money. They have limited financial resilience, so a year or two of losses could push them into financial distress.

To try new practices, they need to be able to rely on partners with 'deep financial pockets', or as financial people would say, 'strong balance sheets'. The global food manufacturing companies, such as Nestle, Unilever and Danone fit the bill nicely. The good news is that shifting how the supply chains are structured also works for them.

Why we want companies to invest in new farming practices

As investors, we want the companies we are invested in to have a long-m viable future. In this case that means having supply chains that are sustainable. For this to happen the food manufacturing companies, and food retailers that directly source, are going to need to build deeper long-term relationships with their farmers. They will provide expertise and training, and in return the farmers will agree to adopt new, more sustainable farming practices.

This new relationship gets tied together by contracts where the farmers agree to provide food of a certain standard, whilst the food manufacturing company agrees to purchase a certain amount of produce at a pre-agreed price. Both parties get more certainty, and as a result the farmers will be willing to take more risk. This is happening already, but not at scale.

This is not as extreme an idea as you might think. I used to be what is known as a 'food staples analyst', which meant that I got to know the financial investment cases for companies such as Nestle, Danone and Unilever. They understood the need to build supply chains that were stable and sustainable. Their business model relied on it - they were not the cheapest food producers so they had to build strong brands.

My experience has been that although a company's work on more sustainable supply chains appears a lot in advertising, it is seen less in financial discussions. The reasons for this are many, but two stand out. First, most financial analysts and investors are not demanding to know more. And second, Danone.

Some of you will know the Danone story, but many will not. The short version is that their CEO, Emmanuel Faber (who I knew and liked) turned Danone into an “enterprise à mission,” France’s version of a B-Corp. Their strategy was branded “One Planet, One Health,” and they created a carbon-adjusted earnings per share (EPS) indicator, linking their financial success (at least in an accounting sense) directly to their environmental performance. All of the things that investors are increasingly calling for.

But, financially the company share price underperformed its main peers, leading traditional investors and activist funds to call for a radical overhaul of the plan. In March 2021 the CEO resigned. The debate around what caused his demise is complex. Some of it looks to have been about execution and expectations management. However, the bottom line is that food industry CEOs and company boards understandably became more cautious about being seen as too environmentally (and socially) focused - 'ESG is good, but profit and share price are more important'.

Our take on this.

Companies in the food industry need to start making their supply chains more resilient, which means making them more sustainable. Which means working more closely with their suppliers, the farmers around the world. To do this, especially post-Danone, they need the support of investors. They need to keep a balance, becoming more sustainable while at the same time enhancing profitability. A tough ask. But if they are to continue to create financial value, its something they need to address.

As investors we need to start pushing for the necessary changes via our engagement. Progress may be slow, as companies balance sustainability and medium term profitability. Without our support it will be even slower.

In doing this we need to make sure that all of our stakeholders - the pension funds, the endowments, the providers of capital, and perhaps most importantly the financial press - understand the value creation imperative of these changes. This is not about being a good global citizen, it's about protecting and enhancing the long-term financial value of the company. The impact of climate change and the degradation of our environment is going to hit the food industry quickly and hard. Business as usual is not really an option any more.

One last point.

We need to understand that companies cannot do it on their own, that they are part of a complex economic and environmental ecosystem. We need to build alliances with governments, NGOs and lobby groups, and even with organisations that we might not always agree with. We may find ourselves working with what five years ago we would have considered unlikely allies.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.