We have enough materials for the green revolution BUT …

To many sustainability specialists, mining is not green, it's brown. It's sometimes thought of as being up there with O&G, some Heavy Industry, Tobacco and Coal. But, we cannot “fix” the problem through exclusions, mining is just too important.

Summary: To many sustainability specialists, mining is not really green, it's more brown. It's even sometimes thought of as being up there with O&G, some Heavy Industry, Tobacco and Coal. But, we cannot “fix” the problem through exclusions, mining is just too important. And if we engage with mining companies, how do we do this? Unlike many other sectors and themes, the issues in mining are not really about CO2 reduction - so the impacts are harder to measure. Many of the challenges are very project and site specific, we can have higher level rules or guidelines, but the real change happens project by project on the ground. This needs more resources, and more expertise.

Why this is important: The role of mining in the transitions cannot be ignored. If we want low carbon electricity we really should also be investing in mining. Which means engagement, in detail and on the ground.

The big theme: The green transition is going to need a lot more mining. Without it most of the transitions will just not happen. There is not a simple alternative, one that “does no harm”, while at the same time providing us with all of the raw materials we need for everything from electric vehicles, through greener buildings and transport, through to renewables such as wind and solar, and the vast amount of electricity grid investment we are going to need.

The details

Summary of a story from MIT Technology Review

In the 2015 Paris Agreement, world leaders set a goal to keep global warming under 1.5°C, and reaching that target will require building a lot of new infrastructure. Even in the most ambitious scenarios, the world has enough materials to power the grid globally with renewables, the researchers found. And mining and processing those materials won’t produce enough emissions to warm the world past international targets.

There is a catch to all this good news. While we technically have enough of the materials we need to build renewable energy infrastructure, actually mining and processing them can be a challenge. If we don’t do it responsibly, getting those materials into usable form could lead to environmental harm or even human rights violations.

Why this is important

As we often say, the real world is complicated. There are no simple rules that allow us to invest in the transitions in a pain free way. I would love to tell you that it's different, but that would not be true. Every choice we make has compromises, trade-offs and consequences. Plus, often lots of negative impacts, which often take place “somewhere else”.

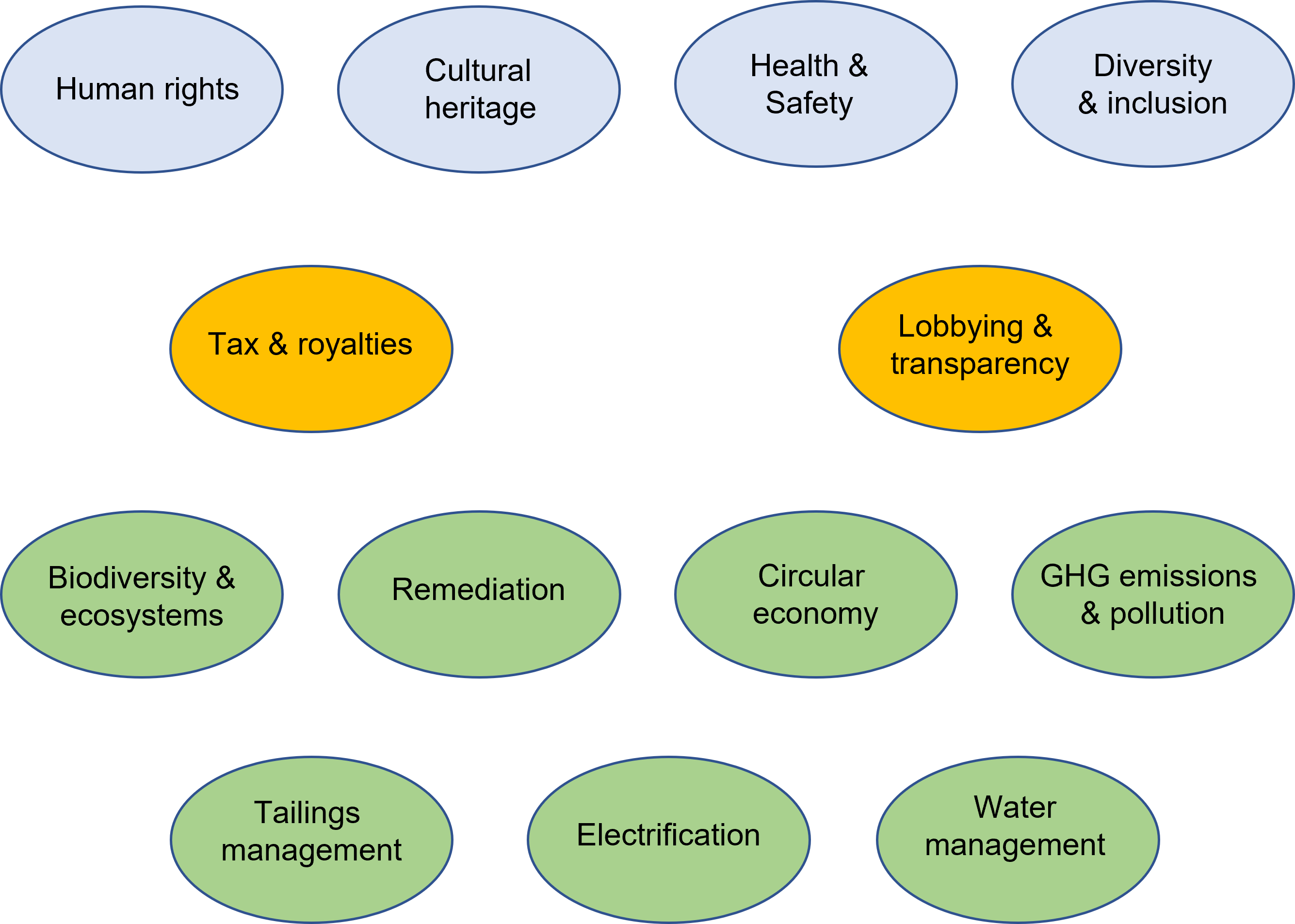

With metals & mining, this is especially true. And to make it harder, the important actions are not things that get easily measured by the standard ESG scoring systems. Yes, CO2 reduction is part of the mix, but it's not the main metric. And the challenge is in the details. What are mining companies doing now, and what can they do, in areas as diverse as human rights, worker safety, environmental protection (including water, pollution, dam tailings, and site regeneration), tax, electrification, recycling and the circular economy, plus of course transparency. In this regard, mining differs from say electricity generation, where often what we want to reduce is network wide CO2 emissions.

Work on these complexities is underway, led by organisations such as the Investor Mining and Tailings Initiative (IMTSI), and the associated Global Tailings Portal. But more investors, both asset managers and asset owners, need to get involved.

To pick a single example of the complexity - water contamination from end of life mines, so just one part of the wider water management issue. As highlighted at a recent conference “mine closure continues to be a significant industry challenge that necessitates proactive planning and substantial financial outlay to manage associated social, safety and environmental risks. According to the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), there are few examples of mines that have received closure certificates”.

One issue that impacts end of life mines is mine drainage. This is metal-rich water formed from a chemical reaction between water and rocks containing sulphur-bearing minerals. The resulting chemicals in the water are sulphuric acid and dissolved iron. Some or all of this iron can come out as solids to form the red, orange, or yellow sediments in the bottom of streams containing mine drainage. The acid runoff further dissolves heavy metals such as copper, lead, mercury into groundwater or surface water. Mine drainage continues long after the mine is closed.

The scale of the problem can seem daunting. Just looking at one US state (Pennsylvania) - according to the local Department of Environmental Protection, the estimated cost to construct and operate all the needed remedial facilities would run into billions of dollars.

Solutions exist, some of them taking a slightly different approach. For instance, work at Monash University in Australia looks at mine rehabilitation, taking account of the specific situation of each mine - built on the basic principles of rehabilitation, tailings management and the potential harvesting of critical metals. It's this last factor that could point to improving the economics. Metals that 20 years ago didn’t have a high value, and hence were just left as tailings/waste, are now valuable, due to the rapid advance of technology.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.