Timber in buildings is good, but not always

The use of timber as a structural element in buildings, replacing steel or concrete, is on the rise. And, in many cases this is a good thing. Timber can be a cost effective, lower carbon and more sustainable solution. But we can sometimes carry this narrative too far

Summary: The use of timber as a structural element in buildings, replacing steel or concrete, is on the rise. And, in many cases this is a good thing. Timber can be a cost effective, lower carbon and more sustainable solution. But we can sometimes carry this narrative too far. Not all timber in buildings is good.

Why this is important: The provenance of materials is key. The carbon footprint of mass timber is impacted by how and from where the wood was sourced and transported, and what happens to it at the end of its useful life.

The big theme: The built environment generates 40% of energy-related GHG emissions and it consumes 40% of global raw materials. So, it's not surprising that it's a target for a lot of new regulation - aimed at making our buildings more energy efficient and improving their sustainability. The good news is that there are many financially viable tools and techniques we can use to deliver on this. But as with all of the transitions, we need to avoid green washing, by ensuring that the environmental and societal gains are real, and that we find ways of actually delivering the financial benefits we are seeking.

The details

Summary of an article in dezeen Magazine

Amy Leedham: Mass-timber buildings can have very high carbon emissions March 2023

Mass timber's reputation as the go-to low-carbon construction material is a problematic oversimplification that is leading to greenwashing, says carbon expert Amy Leedham. Mass timber is a term for engineered-wood products – strong structural components that typically consist of layers of wood bonded together. It is increasing in popularity in the construction industry due to wood's ability to sequester carbon, which means timber generally has a lower embodied carbon when compared to materials such as concrete and steel.

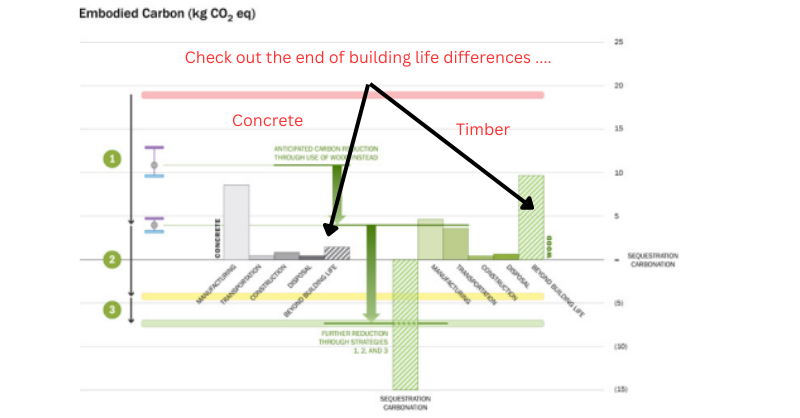

However, according to Leedham, this has caused mass timber to become synonymous with carbon neutrality, leading to the fallacy that all "mass-timber buildings are carbon neutral" due to the stored carbon offsetting the emissions expended by them. One of the reasons it's becoming such a popular building material, is that it can have a significantly lower embodied carbon than steel or concrete," she told Dezeen. But, I say 'can' because it's not always the case.

Why this is important

You will probably have seen numerous articles praising "mass timber" as a more sustainable alternative to concrete and steel. I trained as an engineer in a world of timber. New Zealand has a lot of it, and its a great material for resisting earthquakes (of which we also have a lot!). And so I am used to using it in structural design work. But, as with most transitions, its use is a bit more complicated than that.

Yes, research, including work at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand, where I studied, and another one from the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, supports the view that "throughout its entire life, a large building made mostly from wood would have a carbon footprint up to a third smaller than a comparable one made from steel or concrete". And in many cases this is correct.

But, this is not the full picture, it's a bit of an over simplification, albeit one that appeals to our sense of wanting to make a difference. As always, we need to dig deeper - including where the timber comes from, how its used in the building ie what it replaces, and where it ends up. In the spirit of identifying solutions, not just challenges, engineered or mass timber can be both an environmental and a financial win. But the detail counts.

What is carbon neutrality in buildings?

"Historically, carbon neutrality has focused only on operational carbon. This meant a building was carbon neutral if it could meet its annual operational energy demands with 100% carbon-free energy (operational energy produced without fossil fuels). But, by focusing on operational carbon only, we fail to account for the energy and carbon expended during the extraction, manufacture, transportation, installation and disposal of all the building’s components."

Amy Leedham - carbon expert at environmental design consultants Atelier Ten

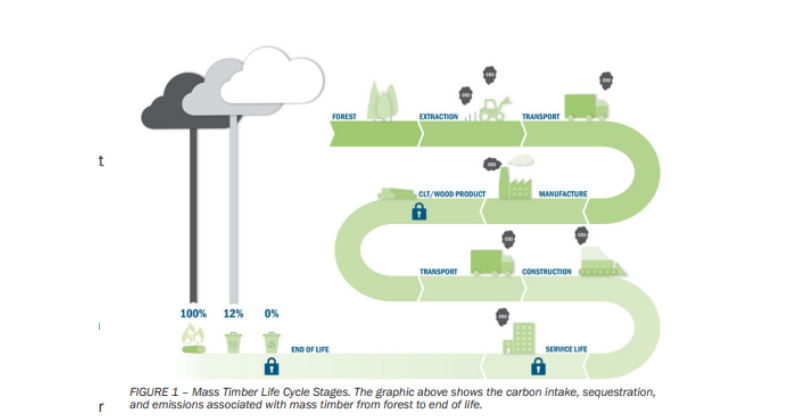

To understand why the use of mass timber in buildings can be a problem rather than a solution, we need to focus on the start and end of the journey. So, from the forest, to a mass timber beam, and then onward to its "end of useful life". Put simply, the carbon footprint of mass timber is impacted by how and from where the wood was sourced and transported, and what happens to it at the end of its useful life. According to Architecture 2030, 70-90% of carbon emissions from buildings are embodied and locked in by the time the building is occupied. This can be way more important than the operational carbon neutrality.

Its worth noting at this point that the report much of this analysis comes from, was co-written by Lever Architects, a leading designer of mass timber buildings. This is not a pro concrete diatribe.

As the chart above shows, the story starts in the forest. In principle, mass timber (as opposed to solid timber beams) can use smaller and lower-quality trees than traditional solid timber construction. As such it creates a commercial incentive for harvesting and utilising these trees in a way which is sustainable. Why can this make a difference? Because in order to manage fires, forest stewards often strip trees, and implement controlled burns, so as to thin out the stock and preserve the more mature trees traditionally used in timber products. This meant that the carbon sequestered by smaller trees would be re-released into the atmosphere as they were burned. Using this "lower quality timber" for mass beams and other engineered timber products can create a positive sustainability outcome. But, of course, you need to be sure that this is the case, that mature trees are not being used to produce mass timber products.

And then of course we have the other end of the life cycle, what happens when the building is demolished. If the wood used in a building's construction ends up in a landfill, it is likely to be incinerated or left to decompose, with its sequestered carbon released back into the atmosphere – cancelling out the carbon benefits.

And sadly, in some countries, a high percentage of timber from buildings does seem to end up in landfill. Taking the UK as an example, some studies suggest that only 10% of wood disposed ends up being recycled, the other 9m tonnes gets dumped. And this can make a massive difference to the carbon implications of using timber in building construction.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.