Restricted and expensive insurance brings flood risk closer to home

Cyclone Gabrielle hit New Zealand, leaving destruction in its wake. The impacts of these events are even more severe if you are not insured.

Summary: Starting around the 12th February Cyclone Gabrielle swept down the east coast of the North Island of New Zealand, leaving destruction in its wake. This particularly resonates for me as I have friends whose families live along that coast, but this blog could equally have been about Nilam hitting Sri Lanka and India, the Philippines typhoon, flooding in Pakistan and Germany, or Hurricane Sandy. The impacts of these events are even more severe if you are not insured.

Why this is important: the '1-in-100 year storm' may be more of a '1-in-20 year event'

The big theme: The UN estimates that climate adaptation spending, just in developing countries, could reach $300bn by 2030. This is on top of the tens of billions being spent by national and regional governments in developed countries. This covers a range of investment themes, including construction of flood defences, building resilience into our essential services, and enhancing disaster responses.

If you are not a member yet, to read this and all of our blogs in full...

The details

Summary of a working paper from CESIFO

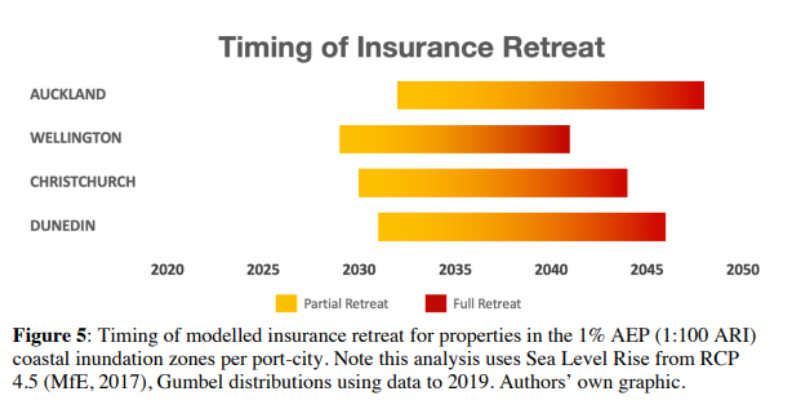

Accelerating sea level rise and increasing storminess, two effects of a warming climate, mean that coastal developments are becoming increasingly exposed to more frequent and severe hazards. Residential insurance transfers risks that are of low enough probability. When the likelihood of damage increases, insurance becomes increasingly costly, until it is no longer viably supplied by commercial insurance companies. Insurance retreat from coastal locations is thus an inevitability once sea level rise causes insurers’ insurability thresholds to be crossed.

Except for the near-term occurrence of an actual disaster, it is the loss of residential insurance that will likely be the first mechanism by which homeowners will experience material economic loss directly attributable to climate change. Since mortgages are typically conditional on insurance (especially at the time of issuance), the withdrawal of residential insurance results in an immediate drop in property values.

Why this is important

The increasing risk of damage from "natural" disasters such as storms, floods and earthquakes, can seem an abstract concept to those not directly impacted. And this is not helped by terminology such as the "1 in 100 year storm", which suggests that these events are unlikely to happen again soon. We suspect this is part of the reason why we still allow new houses to be built on flood plains, and why spending on flood mitigation and disaster recovery and resilience can so easily get delayed, as other, more urgent spending requirements take precedent.

One of our earlier blogs looked at resilience hubs, which are physical, community facilities that support residents, distribute needed resources, reduce carbon pollution, and enhance quality of life. They offer local governments a powerful means of supporting vulnerable populations before, during, and after an extreme weather event or other disasters.

But while they provide practical support before and after an event, resilience hubs do not really help with getting people to think about the risks as being real, rather than some abstract event that "happens to someone else". Which is what we need if real action is to happen. This is where the research work above comes in. Belinda Storey and the team looked at what they called potential insurance retreat - where the risk of an event happening becomes so high that insurance companies stop offering cover.

In New Zealand Aotearoa (NZ Aotearoa), almost a third of the 1.6 million residential houses in the country are located within 1km of the coastline. So, the risk of flooding and storm related damage is high. And studies show that for many properties, these risks are increasing. Mean sea level in NZ Aotearoa will rise by at least 10cm by 2040 (from 2020 levels) - under all four IPCC pathways. And in 2015, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment estimated that in some locations, a 10cm of sea level rise will turn what is currently a 1 in 100 year storm into an event that happens 1 in every 20 years.

Full insurance retreat is when insurers totally stop offering or renewing insurance policies because properties in that location face an escalating hazard and partial insurance retreat is when insurers begin to limit the extent to which homeowners are able to transfer the risk to the insurer. Storey et al reported that private conservations with the insurance industry suggest that partial retreat will begin when the events hit around 1 in 50 years frequency, and that insurance cover will be almost impossible when the event hits 1 in 20 years frequency. For many properties in NZ Aotearoa, they hit this by 2040.

2040 might seem a long time away, but if by 2030 you are already facing more restricted and expensive insurance cover for your home, that feels like an issue we need to start taking more seriously.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.