If only markets were long term, our sustainability problems would be fixed?

What if financial markets were not focused on short term gain? What if markets are actually long term focused, but that they believe that the pace of the sustainability transitions will be so slow that the business as usual scenario is still financially optimal.

Summary: Many of the interventions in Sustainable Finance are driven by an belief that financial markets are short termist, that they focus too much on near term profits and not enough on long term value creation. But what if this wasn’t true. What if markets are actually long term focused, but that they believe that the pace of the sustainability transitions will be so slow that the business as usual scenario is still financially optimal.

Why this is important: If markets really are long term focused, this gives us some important levers. One is to change the narrative, to persuade the financial markets that starting to change now makes more financial sense than waiting. To do this we need two things. We obviously need action by governments, but we also need action from the providers of capital, the savers. They need to put pressure on their representatives, the pension funds, asset managers and the like, to build a system that creates the outcomes, both societal and financial, that meets their needs. For this to happen they need education.

The big theme: We all know that if the planet is to achieve its decarbonisation and transition targets, we need to engage the private sector. Just to deliver net zero, we need to invest $4-5 trillion every year out to 2030. This is over double what we invest now. On top of this we also need to invest to preserve and rehabilitate our environment, social systems and biodiversity. Governments and society have an important role to play but they cannot do this on their own. We must find ways to actively engage the finance sector.

The Detail

Transcript of a podcast interview with Ariel Babcock, formerly head of Research at FCLT Global : Published by EY

One of the issues we find frustrating about the “are financial markets short termist” debate, especially as it relates to sustainability, is how quickly it can move from …here is some evidence of short termism, through to …, and this short termism is what is causing damage to the environment, climate and stakeholders. While there is some evidence that financial short termism is both real and probably increasing, the research suggests that its linkage to sustainability is much less certain. And so what we liked about what Ariel discussed in the interview, once you got past the slightly clickbait title (what is market short-termism’s perceived impact on ESG investments?) was the focus on the financial and economic advantages of having a long term focus when making investment decisions.

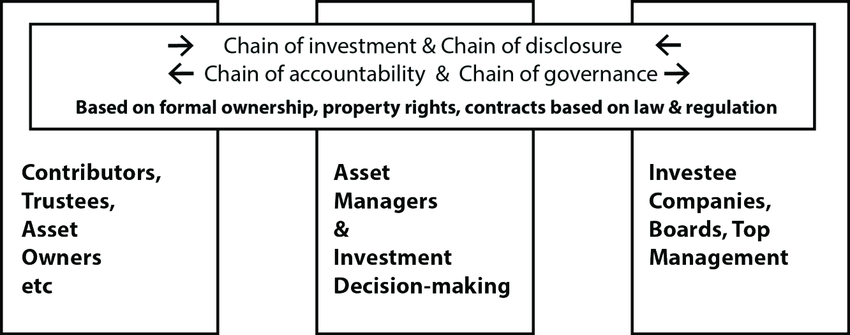

Her framing of the issue is also pretty useful. She starts at both ends of the investment process, before thinking about what happens in the middle. Specifically she says that “across the investment value chain, there are savers on the one hand that have very long-term goals for their capital. They’re saving for retirement. They’re saving to fund their children’s education. They’re saving to buy a home, things like that. On the other end, you have companies who similarly have very long-term goals for their organisations, and they need capital to fund those growth initiatives.”

And then in the middle, you have a whole lot of other players, asset owners, asset managers, sometimes capital market participants, the structure of the markets, boards, management teams, regulators etc, who interrupt those long-term goals. This is similar to the argument from researchers at the Erasmus Platform for Sustainable Value Creation at the Rotterdam School of Management - that the length of our investment value chains means that the objectives of the savers can get lost long before the money hits companies. So, in a way the right question is not are financial markets short termist, but instead, how can we best align our investments in companies with the objectives of the people and organisations who provide the money in the first place.

Why this is important

The argument about “are financial markets too short term focused” has raged for as long as I have worked in the industry, roughly three decades. A more recent addition to the debate is the reasoning that this short termism is one of the reasons why financial markets are “failing” to solve the sustainability challenges.

And you can see the appeal of this. The implication is that if only we can get the finance industry to think more long term, companies will naturally start to fix some of society's biggest challenges. A more subtle variation on this is the pitch that if we measure and report something, say an environmental or social impact, then companies will be incentivised to act to improve it.

The evidence for short termism is mixed

Despite what you may have read, the evidence for markets being short term is mixed. On one hand, those of us who work in the industry know that the pressures on companies to deliver their quarterly earnings targets are fairly high. Missing targets is largely seen as a negative event, and they normally lead to a (short term) share price fall. And no CEO or IR team wants to have to explain to their board why a share price fall happened. And hence, so the argument goes, companies will cut spending such as R&D, innovation, or marketing to make sure they “hit their numbers”. Which in turn reduces their potential to create value in the longer term.

Back in July 2020 , the European Commission published the “Study on Directors’ Duties and Sustainable Corporate Governance”. (Editors aside - why do all of these reports have such boring titles ?) The underlying premise was that “the focus of corporate decision-makers on short-term shareholder value maximisation rather than on the long-term interests of the company reduces the long-term economic, environmental and social sustainability of European businesses”. This is an often quoted example that "proves" that the market is short termist over long term thinking.

And it's more complicated than it first appears

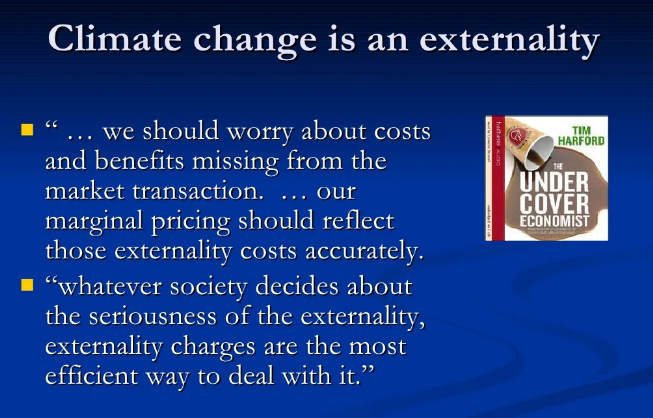

But, as with most things in sustainability finance, it's actually a lot more complicated than this. What people identify as showing short termism might actually be showing something else. For instance, there is a really good research paper by Roe, Spamann, Fried & Wang (published by the European Corporate Governance Institute), that argues that much of what observers call short termism is actually more about externalities. Or putting it another way, investors can have a long term perspective and still not fully price in things like climate change, because they are external, they don't (yet) impact company value.

Why might this be? One reason the authors point to is conflicting interests. They ask the question …

And we argue that there is another, in some ways more compelling, reason. Put crudely, many investors believe that, despite all of the talk, sustainability related change will either just not happen, or if it does, it will happen more slowly than is talked about. And this is not because of climate denial, most people know that climate change is real. It's much more to do with a belief that governments will dodge the hard choices.

And this can have a material impact on the financial returns they can deliver. As Tom Gosling argues in his recent working paper on fiduciary duty (Can Investors Save the Planet? - NZAMI and Fiduciary Duty), if there is a real risk that climate action doesn't happen as forecast, then investing in line with achieving say the 1.5 degree Net Zero goals, is likely to result in lower financial returns for your beneficiaries.

This is a variation on the free rider challenge that so bedevils activism and shareholder engagement. Acting on climate risk has a cost. Yes, there will likely be a future payoff, from greater operational resilience, or better positioning for future profitability, or from the benefit to the wider society. But we need to be honest, there is an upfront cost, and its often material. And for the negatives of climate change to be avoided, we all need to act (or at least a lot of us).

And so if I act, but no-one else does, or even worse, if I act and my government just stands by and does nothing, then I incur the costs and only get part of the benefits. Which means I earn less profit/investment return than a company and/or investor that just sticks with “business as usual”.

So, how does this impact investor decision making?

To make sense of this we need to understand how investors value companies. In simple terms, a company (or any investment) is worth the discounted value of the cashflows it can generate over time. And here we hit our first "what if", because knowing what the future cashflows will be is tougher than you think. …

“Prediction is very difficult, especially if it's about the future”. Niels Bohr

Let's pretend for a moment that the company provides long term profit guidance. This is fairly common, as many companies talk about their operating model, from which we can infer a long term growth rate of their profits. From this we can make an estimate of the cashflows the company can generate, and using our best estimate (guess) of the discount rate (which adjusts for the time value of money), we can estimate a fair value for the company.

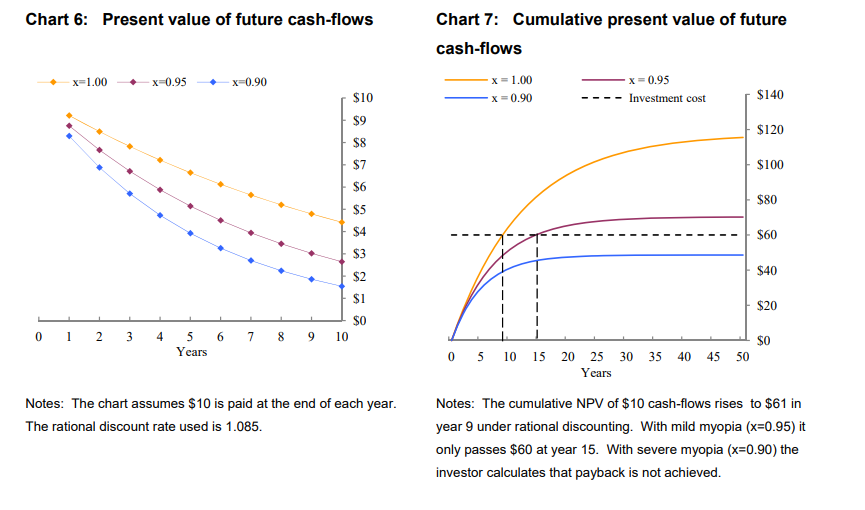

So, what if investors are less optimistic about the future than the company. Then the fair value they estimate will be lower than what the company expected. How much less optimistic do we need to be ? As it turns out - not very much less. Andy Haldane and Richard Davies (both from the UK Bank of England) looked at this. Among their conclusions were that if the markets analysis was only 10% less optimistic (the blue line in the charts below) than the company's guidance (the yellow line), then investment opportunities that companies should take up will not get funded. And even a 5% difference (the purple line) can materially impact perceived value creation. Trust me, 10% less optimistic is not much in longer term financial forecasts.

How this relates to sustainability finance

That's straightforward. If the financial markets assume that the pace of change will be slower than the politicians are talking about, then the future cashflows that a company can generate from the changes will be slower (or more distant in time). And as Haldane & Davies said, only a 5% to 10% more pessimistic outlook can turn an investment opportunity from viable to a “no go”.

First and most obvious, we need governments to act in a consistent manner. No flip flopping. Simple policies that look 10 or even 20 years out into the future and that say, “our support, both regulatory and financial, will be there for a long time”. Good examples of this include the impact of contract for differences on the build out of renewable electricity generation in Europe, and the recent US Inflation Reduction Act.

And second, less obvious, but just as important, we need the original providers of capital, the savers and their representatives (the pension funds and family offices) to start saying “we know the transition has risks, but we are prepared to forgo short term financial upside for the longer term gains we can see in the future”.

And this cannot be a vague, “we want our money to do good as well as earn a fair financial return”. It has to be detailed and specific. It has to be built on a clear understanding of the risks and tradeoffs as well as the opportunities. Putting it simply, the original providers of capital need to go into this with their eyes open - for this they need education that talks about the financial implications of the transitions, warts and all. There is no win/win. That route shuts down the debate.

This means that what is known as client education will become ever more important (a subject we will keep coming back to in future blogs). We argue that the organisation that cracks this, that builds real trust with their clients, will be the long term winner.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.