Human rights is not just a values issue

It is increasingly understood that human rights is no longer just a values and ethics question. It's also now very much an investing issue, one that can have a very direct impact on a company's long term value creation.

(or why we don't send children up chimneys anymore)

For many people human rights is a values and ethics issue. There are company behaviours and actions that are just plain wrong. And they don't want their capital, their money, invested in companies with poor human rights records and practices. And for many years, that was as far as it went. Human rights, with a few major exceptions, was a moral issue.

And then the world started to change. Society's views on human rights became more enshrined in the law. In many ways this should have been expected. Public opinion leads, and the politicians follow. And over time the penalties move from ineffective sanctions, through fines, to action's that have material impacts on companies.

Now, it is increasingly understood that human rights is no longer just a values and ethics question. It's also now very much an investing issue, one that can have a very direct impact on a company's long term value creation. Companies that do not prepare for this new world will lose competitive positioning; it's not just about paying fines anymore. Companies increasingly bear responsibility for what happens in their supply chains, and they face legal action in their home country for acts elsewhere.

This does not make the ethics aspect of human rights any less important to investors. But, what it does add is a double hit for companies (and investors) that pay lip service to human rights, those who see it as a box ticking exercise. First, people are much more willing to call out greenwashing. And second, not properly taking human rights into account in investment decision making can have material implications for financial value.

The details

Much of what we read around human rights and it's impact on investors, starts with the law or regulations. Companies must do this, or they will suffer fines etc.

We think the thought process needs to start earlier - we need to start with what societies standards are, and how they are changing. Public opinion leads, and the politicians follow. In the same way that companies and investors need to track and stay ahead of changes in technology, or new consumption patterns, they also need to stay ahead of changes around human rights. And this means thinking outside of the box - human rights impacts a whole range of wider social and environmental issues. If companies are not prepared, they face material damage to their long term value creation.

This blog was previously published as a Deep Dive in December 2022.

Our view on what constitutes acceptable work practices changes, as societies become safer and more prosperous. Maybe slowly, but they change. Up until the 1840s, children under 10 years old used to be allowed to work in UK underground mines. Now, the debate is less about working practices in a company's home country, and more about how it treats its employees elsewhere.

Our main point is a simple one. What we think of as socially acceptable behaviour by companies follows our wider values. The legal framework normally plays catch up, sometimes driven by a reaction to events that are seen as being so horrendous, that they create a consensus to make sure that something "like that" should never happen again.

Sometimes social pressure on its own works; sometimes we need the law but, and this is the important point, it's not the law that drives the process. It's social pressure. Enough social pressure and you can be sure that the law will follow. And social media spreads the word faster than Charles Kingsley (the author above) could ever have imagined.

But of course, its more complex than this. Social pressure on its own is seldom enough. Without legal rights those who are vulnerable will not be able to obtain redress or justice, and those with power and wealth will have disproportionate strength. The law is not abstract notions in a language few can understand (although sometimes to non lawyers it might feel like that)– the law is there to ensure that everyone gets a fair deal, to avoid oppression, and to obtain redress for those who suffer abuse.

We are "lucky" to have on our team an internationally recognised expert on human rights. Kristina Touzenis created the International Law Unit at the International Organization for Migration - IOM, the UN Agency for Migration, and served as Head of the Unit from 2011 to 2020. This gives us a fairly unique, and valuable, perspective.

At this point most blogs on human rights would begin to talk about values, why being a good corporate citizen is the right thing to do. It protects a company's reputation, and it supports staff recruitment and retention. Plus, staff who work for companies whose values they believe in and support, will be more productive. This is all largely true, and it is a really important aspect of the debate.

But, today, we want to take a different tack.

We are going to look at Human Rights as an investing issue, one that can have a very direct impact on a company's long term value creation. This is not to diminish the values-based arguments. Many investors want to know that their capital is used in a way that is aligned with their values. And some are working out that they are effectively "universal owners" - so these systematic issues have the potential to materially damage the returns from their wider portfolios of equities and debt. Put simply, universal owners are effectively invested in the wider society, and so externalities that damage wider society also damage their portfolios.

To make sense of this different approach to human rights, let's step back a bit.

Let's imagine for a moment you run a company (or invest in/lend to one).

You have supply chains; they might bring you agricultural products, or they might bring in the outputs of the metals and mining industries. And you have production processes, your own or those of your suppliers, that might use fossil fuels or chemicals. And how you get your products to customers probably uses fossil fuels. I could go on, but by now hopefully you get my drift. The company is embedded in a wider system.

Now, let's turn back to the human rights theme. Countries are increasingly requiring you to know more about how your raw materials and end products are produced and where they come from. Does the process result in environmental damage? Are you or your suppliers using child labour, or exploiting workers and violating their rights? Are your processes contributing to abuses of the human rights of indigenous peoples.

Now, at this point we normally get the response that these are not issues for companies to fix, they are matters for governments, and we, as companies or investors, "always" comply with local laws.

Well, sorry, but the law, and the legal framework within which it's set, is changing. Just as with sending children down the mines or up chimneys, social pressure is leading to new legal frameworks. These are making it a company's responsibility to know where their raw materials come from, and to know if human rights abuses are taking place in their supply chains, and if they are, act to fix them. And these new frameworks mean that you can be pursued in your home country for actions elsewhere. And you might also be impacted by the actions that legal challenges force governments to take, making them actually implement international agreements, rather than just ratifying them and carrying on as if nothing has changed.

States are rapidly realising that businesses (companies/investors) are a

group of legal entities with a massive impact on human rights as well as the

environment, and that specific tailored legislation is necessary to regulate that impact.

In this new world, the sensible thing for a company (or an investor) to do - is prepare. Supply chains are often long, they can take years to rebuild. Many industrial processes are complex, changing them overnight is difficult. So, rather than wait for the law to hit, surely, it's better to anticipate and prepare.

This is why human rights is not just a values issue, it's also a value creation issue. Companies that do not prepare will lose competitive positioning; it's not just about paying fines anymore.

Let's dig deeper into this...

We have three examples:

- responsibility for supply chains

- legal action in your home country for acts elsewhere; and

- the impacts of international agreements.

Supply chains - they are becoming your responsibility now

We have written a fair bit on this over the last year or so, so none of this should be a surprise to our regular readers.

Back in November 2021 we highlighted the passing of the German supply chain law. You can read more about this in our Daily Perspective blog, published late last year. This law, which came into force from January 1st, 2023, makes companies more responsible for what happens in their supply chains.

In practice this means companies should be working to address issues around:

- labour standards in supply chains (including how these are enforced and controlled)

- fair recruitment practices

- effects of their operations on societies (including land and property issues; access to clean water; access to education)

- influences on participation (including avoiding undue influence on democratic processes)

- how well they comply with the "do no harm" requirement (a holistic evaluation of the impact of their investments and practices); and

- introduce results-based reporting (including transparency in challenges met and how they were dealt with).

This is not a two-minute job, remembering that increasingly companies who do not comply risk facing penalties.

But it's not just Germany (a point we made when we first published). This new law can be seen as the latest steps in a fairly long process (although, referring back to the children up chimneys process, we are closer to the end than the start). Already in 2015, the UK passed the Modern Slavery Act, which includes “Transparency in Supply Chain Provisions”, requiring companies with a turnover higher than £36 million to publish statements on the actions they take to avoid human trafficking and slavery happening in their business and supply chains. France passed a Vigilance Law (“Loi de Vigilance”) in 2017, which mandates French companies with more than 5,000 employees in France, or 10,000 worldwide, to adopt plans to address risks around human rights, occupational health and safety, and environmental damage in their supply chains. And, in 2019 the Netherlands adopted their Child Labour Due Diligence Law which will require Dutch companies to inspect their supply chains for child labour. If they find any instances, they are required to prevent it.

And the momentum is continuing. The European Union has moved to ban the import of products made with forced labour (we wrote about this in Oct), and in November, we wrote about how pressure is growing to act on similar issues within Europe (specifically in the Italian agriculture sector).

And then more recently, the European Parliament endorsed new regulations to minimise the risk of deforestation and forest degradation associated with products that are imported into or exported from the European Union. Regular readers will spot that we flagged this as coming, in a blog from January 2022. And we discussed it again in a long blog in July of this year.

The regulation sets mandatory due diligence rules for all operators and traders who place, make available or export the following commodities from the EU market: palm oil, beef, timber, coffee, cocoa, rubber and soy. The rules also apply to a number of derived products such as chocolate, furniture, printed paper and selected palm oil based derivates (used for example as components in personal care products). A review will be carried out in two years to see if other products need to be covered.

Moving away from agriculture, New York State proposed a new law (snappily titled Assembly Bill A8352/S7428), that aims to reduce the social and environmental impacts of the global fashion industry by requiring major fashion brands to (1) map out their supply chains, (2) assess and disclose their social and environmental impacts, (3) ensure their immediate suppliers pay their employees a living wage, and (4) set emission reduction targets for their operations. The bill was introduced by Assemblywoman Dr. Anna R. Kelles and New York State Senator Alessandra Biaggi, respectively, with support from influential fashion and sustainability nonprofits including designer Stella McCartney, the New Standard Institute, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and the New York City Environmental Justice Alliance. This law has been pending for some time now, and it still may not get passed, but it's indicative of where legislative thinking is heading.

Legal action in your home country for acts elsewhere

As we said back in August 2021, human rights enforcement doesn't respect international boundaries anymore. Various decisions on jurisdiction have opened the way for parent companies to be held accountable for the acts of their subsidiaries, as well as for acts they commit on foreign soil, when the justice system in the affected country is deemed to be too lengthy or not effective.

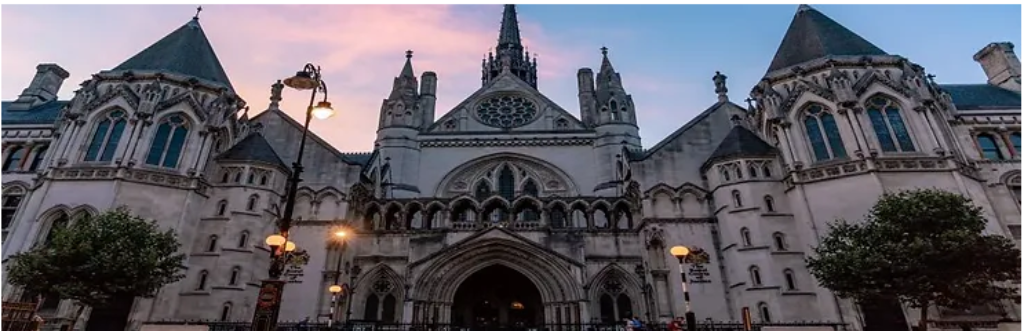

Recent blogs have highlighted a number of cases. In August 2021, we discussed the decision by London’s Court of Appeal to reopen a $7 billion lawsuit by 200,000 claimants against Anglo-Australian mining giant BHP – a case regarding the dam rupture behind Brazil’s worst environmental disaster in 2015. This built off earlier decisions including in 2019 the UK Supreme Court allowing Zambian villagers to sue miner Vedanta in England for alleged pollution in Africa, and in February 2021, when they permitted Nigerian farmers and fishermen to pursue Royal Dutch Shell over oil spills in the Niger Delta.

We followed this up in October 2021, when we wrote about the case of the Kenyan tea pickers, who filed a case in Scotland seeking damages for musculoskeletal injuries while on duty. What these, and other cases show, is that violations of rights overseas are no longer out of reach of jurisdictions with a tradition of respect for the Rule of Law and human rights. And that there is an obligation on private entities operating in jurisdictions other than the one where they are domiciled, to operate according to human rights and labour standards. Or they risk paying the price.

International law - or making countries fulfil their obligations

This is the third element of the wider human rights debate that companies and investors need to track closely. This one is subtly different - whereas the previous two examples have involved potential compensation, or maybe fines, in this case a legal challenge could force countries to take action against companies - either banning some operations altogether or at a minimum, imposing limitations of their operation. It's probably best to illustrate it with an example.

In October 2022 we wrote about how the Torres Islanders’ in Australia won a legal case involving climate damage and their right to enjoy culture and family life, which opens up yet another avenue for legal challenge on human rights. During the September 2022 session the UN Human Rights Committee found that Australia violated the rights of Torres Strait Islanders' to enjoy culture and family life. The joint complaint was filed by eight Australian nationals and six of their children. All are indigenous inhabitants of Boigu, Poruma, Warraber and Masig, four small, low-lying islands in Australia’s Torres Strait region. The Islanders claimed their rights had been violated as Australia failed to adapt to climate change by, inter alia, upgrading seawalls on the islands and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

It is important to note that the entity being held accountable here is the Australian State. This is very different from the trend we recently highlighted, where NGO's and other entities are using legislation to 'hold companies to account'.

States are the duty-bearers that can be held accountable in front of the Committees. What has been adjudicated is that the Australian government did not live up to its obligation to protect the Islanders from adverse effects of actions by a number of actors - including addressing greenhouse gas emissions by private companies.

What happens next. We don't expect rapid change. The last we saw was that in June, members of the Federal Court were heading off for on-country hearings, to be held in community halls across the land of the Guda Maluyligal people of Boigu and Saibai islands.

This case still has some way to run, but we see it as opening up interesting new avenues in terms of grounds for litigation against any entity which causes environmental degradation or does nothing to prevent it. In turn this is likely to make States more willing to take action against companies who may be infringing on rights which up until now may have been seen as marginal to the environmental debate.

Conclusion

We started this blog with the big theme ...

Human rights are a big theme in their own right, but they are also linked to a series of wider social and environmental topics that are rapidly moving up the agenda. Companies and investors need to stay ahead of the curve on this. These are not just good corporate citizen topics anymore; they are becoming a critical driver for company's long term financial success or failure.

We started off arguing that human rights are no longer just a values activity (as important as this is), there are increasingly financial aspects. We can see (at least) three ways that the long-term financial success of a company can be impacted by changes in how human rights are being interpreted and acted upon. The first, and perhaps most immediate, is in supply chains. Put simply, what happens in supply chains is increasingly being made the responsibility of companies.

Second, various decisions on jurisdiction have opened the way for parent companies to be held accountable for the acts of their subsidiaries as well as for acts they commit on foreign soil. It's no longer enough to say, "we obey local laws", especially when the justice system in the affected country is deemed to be too lengthy or not effective.

And thirdly, there are now more legal avenues for citizens to use to force countries to take action against companies. The end result could be either some activities being banned altogether or at a minimum, having limitations imposed on them.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.