How much will it cost?

One of the questions we often don't ask enough is how much will this project really cost? I don't mean the estimate, I mean how much will we need to spend by the time its finished. This is a question that the UK government should have asked about its latest high speed railway.

Summary: One of the questions we often don't ask enough is how much will this project really cost? I don't mean the estimate, I mean how much will we need to spend by the time its finished. This is a question that the UK government should have asked about its latest high speed railway. Work on the first phase of the project - between London and Birmingham - is well under way and that part of the line is due to open by 2033. But there have been a series of reports over the years that the real cost will be way over the initial estimate. And now there is speculation that the railway might not even make it to London!

Why this is important: While the failures of big projects make great headlines, we should also care for another reason. We are going to need a lot more mega projects in the coming decade.

The big theme: The sustainability transitions are going to require new infrastructure, a lot of new infrastructure. Everything from new wind and solar farms, through electricity transmission, nuclear and hydro, buildings, bridges and railways. To make sensible decisions about which options we prefer, we not only need to know what they do for things like CO2 reductions, we need to know how much they will cost. Overly optimistic estimates will lead to poor allocation of resources and, from a finance perspective wasted capital and lower than expected returns.

The details

Summary of a story from The BBC

The UK Chancellor has confirmed that the HS2 rail line will go all the way to London Euston, following a report the scheme may no longer reach the capital's centre. The Sun newspaper reported that rising inflation and construction costs mean trains may terminate in west London instead.

The estimated cost of HS2 was between £72bn and £98bn at 2019 prices. A report published last October found it was unlikely that the £40.3bn target for the first section of the line would be met. Transport Secretary Mark Harper said HS2 was "experiencing high levels of inflation" and it was working with "suppliers actively to mitigate inflationary increases".

Let's look at why this is important...

Why this is important

As a civil engineer, I have always had an interest in how much infrastructure costs, and how likely it is to be finished on time and to budget. Unsurprisingly, I have brought that interest with me when I moved into the world of finance. Too many people take cost estimates on trust, despite the fact that we intuitively know that they are often (or maybe even normally) wrong. This applies to everything from your company IT upgrade, through your home extension or kitchen upgrade, where you may be a victim of the lowest bid, and major projects sponsored by governments, where we are often victims of politically motivated over optimism.

You would think that the private sector was better at estimating, after all its real money to them, and they are supposed to know what they are talking about. But, it turns out it depends. One-off projects generally end up being finished later and costing more, while anything that is modular seems to do better. And, surprise surprise, the better you plan, the less likely your project is to go over budget. Which means that HS2, was doomed from the start, poorly planned, politically motivated and very bespoke.

While the failures of big projects make great headlines, we should also care for another reason. We are going to need a lot more mega projects in the coming decade. A recent report from McKinsey for instance, estimates that "spending on physical assets that could help reach net zero would need to rise from $3.5 trillion spent per year today to $9.2 trillion annually. Total spending through 2050 could reach $275 trillion".

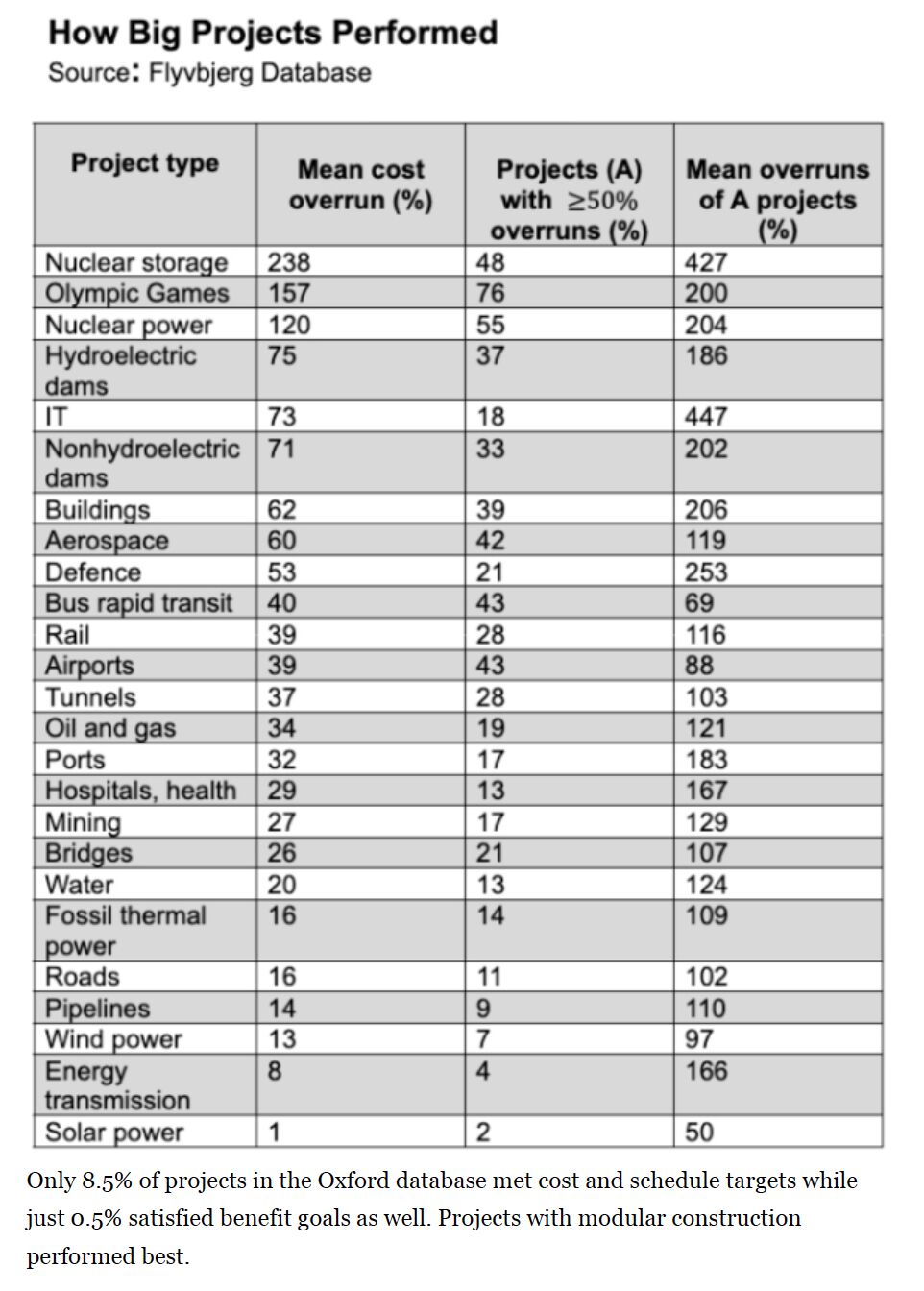

And, within that spending we will need to make some tough decisions between options. For instance, do we build nuclear or pumped storage hydro, or can we achieve the same aim using solar plus batteries and interconnections. Now, we know that we are making these decision under conditions of uncertainty. Some of the technologies are not yet fully commercial, and with some, we don't know how much better they might perform in three or five years hence. But, we would like to think that we could broadly rely on estimates of future costs. Here the work of Professor Bent Flyvbjerg, at Oxford University might help you. He set up the now famous database, that records some 16,000 mega projects across 36 countries.

It appears we are pretty good at estimating the cost of some things, including solar, wind and transmission assets. But we are poor at others. I am guessing you are probably not going to fund the next Olympic games, but one way or another we will all pay for nuclear storage and hydro. So, when thinking about finance decisions that require trading off one technology over another, lets think some more about the likely eventual costs, and what they might mean for our financial return expectations.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.