Food price rises - we can do something but ...

Recent analysis suggests that high food prices will continue for some time, and that the impact will be more severe than we initially thought. We need to think differently about how and when we use fertiliser, and how this fits into our wider system of agricultural practices.

Summary: Unless you live under a rock, you will know that food prices have risen and risen sharply. Analysts increasingly believe that the main driver is gas and energy prices, which impact farmers mainly via fertiliser costs. Recent analysis suggests that not only will this continue for some time, but that the impact will be longer lasting than we initially thought. We need to think differently about how and when we use fertiliser, and how this fits into our wider system of agricultural practices. This will take time, but its worth starting.

Why this is important: Energy prices directly impact the cost of food production. That will drive inflation.

The big theme: There are real concerns about our ability to feed the world, while at the same time trying to reduce the impacts on our natural world. The resources are not limitless. One major pressure point is nitrogen fertiliser. It does a lot of good but its also a double edged sword.

The details

Summary of a report from The Conversation

Food prices in the UK are at their highest for 15 years and something similar is happening in almost every country around the world. The situation is set to get worse as high fertiliser prices, and resulting lower yields from reduced use, may cause further food inflation in 2023. A recently published research report in Nature Food suggests these price rises will lead to many people’s diets becoming poorer, with up to 1 million additional deaths and 100 million more people undernourished. This isn’t just happening because of reductions in food exports from Ukraine and Russia, which are less of a driver of food price rises than feared. And unlike previous food price spikes higher food prices may be set to last. This could be the end of an era of cheap food.

Why this is important

It will come as no surprise to you that food prices are much higher than only a year ago. The underlying drivers of these price rises, agricultural input costs, could result in food costing between 60% & 100% more in 2023 cf 2021. Plus, these trends could have flow-on effects in terms of lower future food production, and an expansion of agricultural land - leading to even more biodiversity loss. While many analysts blame the lower food exports from the Ukraine, the article authors argue the bigger problem is high energy prices, which they expect to continue.

Energy prices directly impact the cost of producing food, largely by increasing the cost of nitrogen fertilisers. This is mainly made with natural gas, the input raw material which accounts for up to 80% of the total cost of fertiliser production. The report modelling estimates that by 2030 agricultural land could increase by 200m hectares (the size of most of Western Europe), as farmers look to offset the impact of lower fertiliser applications (as they try to manage costs) leading to lower agricultural yields.

But, it doesn't have to be that way. A recent report by the Canadian National Farmers Union (hardly a radical organisation normally), highlights that while nitrogen fertilisers have many benefits, they also have drawbacks. They describe a treadmill like system where farmers add more and more fertiliser (hence adding to their input costs), as they search for higher and higher yields. The argument they make is that the reasons for stepping off this treadmill go well beyond the benefits this would bring to the environment. By endlessly chasing yields farmers both depress the prices of the goods they sell (over supply) and increase the prices of their inputs (over demand).

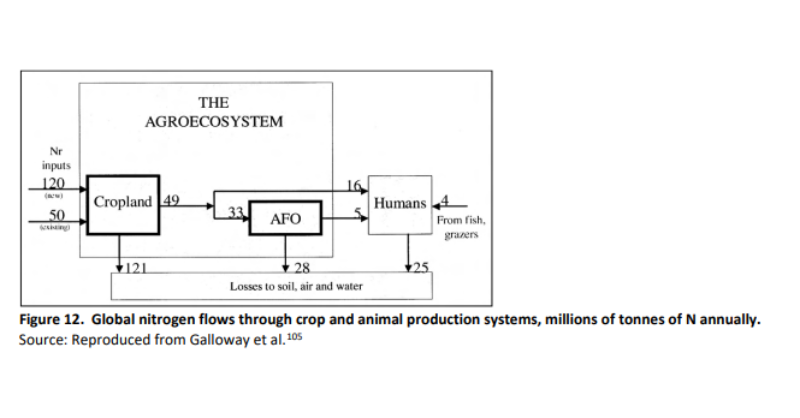

And remember, very little of the nitrogen we apply ends up doing us any good. It was estimated that globally we apply some 170 million tonnes of nitrogen to our soils. Of this 120 million tonnes is from nitrogen fertiliser and biological nitrogen fixing crops such as soybeans. The other 50 million tonnes comes from crop residues and manure. Of that 120 million tonnes, only 49 million tonnes makes its way into our food, the rest goes into our atmosphere, and water systems. And, if we just consider nitrogen fertiliser, under half makes it to the plants we are trying to help.

What are some of the possible solutions?

As with most transitions, there is no single, simple silver bullet.

There are new ways of getting nitrogen into the soil, such as biofertilisers. And there are techniques for making better use of the fertiliser that does get applied, such as the “right time, right placement, right source & right rate” model that the Canadian NFU discusses in their report. They estimate that using this can reduce nitrogen related emissions by 30%.

Plus, it's possible that practices such as agroeconomy (optimising the use of natural resources while reducing the use of synthetic pesticides and fertilisers) can make a positive difference to farm profitability. A recent report from the French think tank France Strategie (reported in Euractiv - my French is not up to a technical translation), identified that agroecolgical farms generally have better medium term profitability than their traditional counterparts. And, that farms that switch to organic cultivation see their direct profit margins increase by 25%. Basically the model results in lower yields but also lower costs.

This is consistent with a 2018 report in the Journal of Life & Environment research that found that while regenerative fields had 29% lower grain production, they reported 78% higher profits over traditional corn production. We accept that more peer review science is needed on this topic.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.