Innovation in feeding cattle

Innovation in livestock feeding can minimise their impact on the environment, improve their health, and help with logistics.

Summary: Innovation in feeding cattle covers a number of areas including minimising their impact on the environment, improving their health, and in the logistics of feeding.

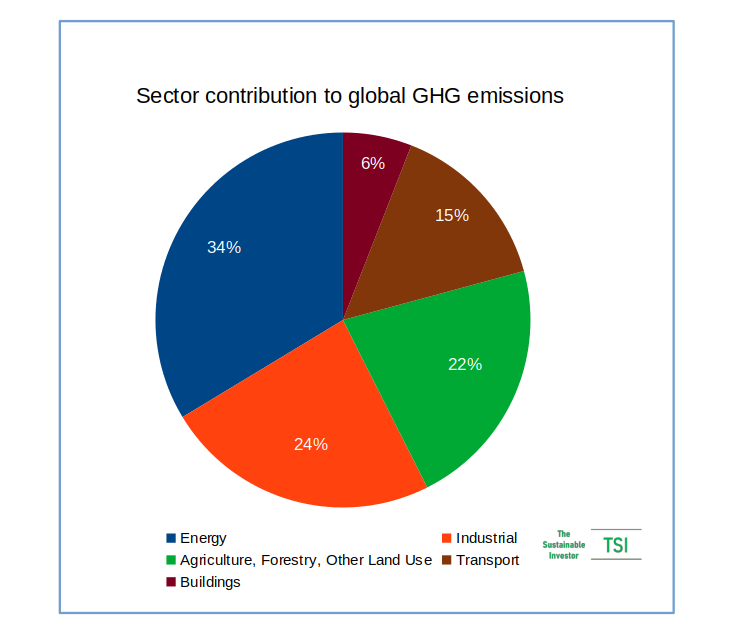

Why this is important: Agriculture, forestry and other land use generates 22 percent of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and utilises 72 percent of global freshwater supplies. Meat is responsible for a big part of that impact and how cattle are fed is a significant aspect. It is also an important battleground in the fight against antimicrobial resistance as antibiotics have been historically overused in concentrated animal feed.

The big theme: There are real concerns about our ability to feed the world, while at the same time trying to reduce the impacts on our natural world. Agriculture (and its sibling, aquaculture) sits at the intersection of a number of UN Sustainable Development Goals. The goals are either directly relevant (for example, goal 2: zero hunger) or have a causal relationship (for example, education improving with better nutrition and less pollution). Reforming agriculture is going to require massive social and economic change and disruption to production methods, to supply chains and to employment.

The details

Why this is important

Agriculture, and specifically meat production, has a big environmental footprint. The two main areas are GHG emissions and water usage. In addition, how cattle are fed can have important implications for their health and the use of antibiotics in their rearing.

Let's take a look in more detail...

Emissions

More than one-fifth of global GHG emissions come from agriculture, forestry and other land uses.

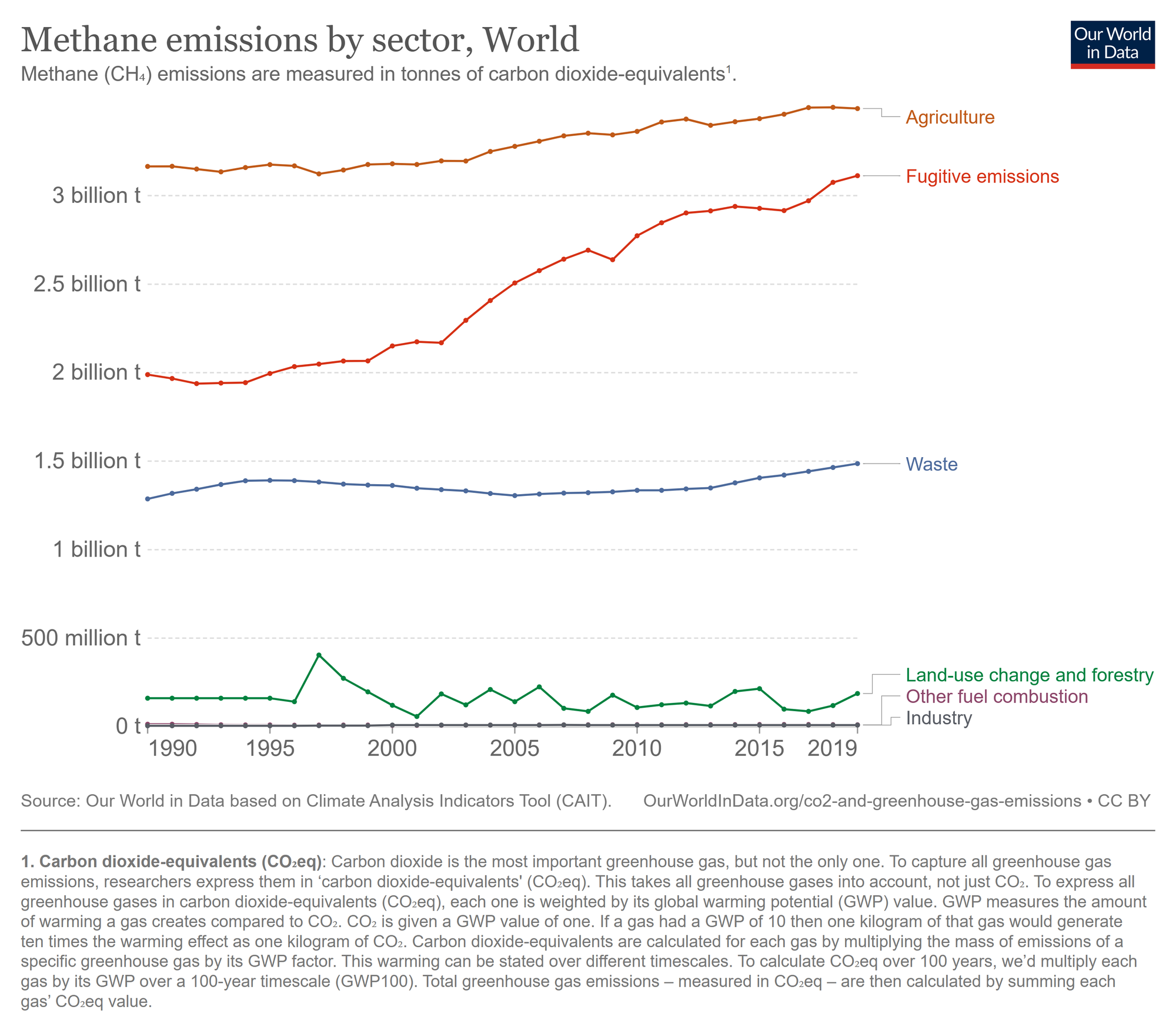

The focus is often on CO2, but another key GHG is methane, which is particularly relevant for farming. Agriculture is the biggest source of anthropogenic methane emissions, followed by the energy and waste sectors.

Methane emissions from livestock digestive systems account for three-quarters of farming emissions. What we are talking about here is burping and farting.

Cows, sheep and goats and other 'ruminant' animals have different stomachs to us. Their stomachs are divided into four sections with the first section, the rumen, being where all of the ... ahem... action takes place. There are millions of microbes in their rumen that help ferment and break down high-fibre food like hay and grass into simpler molecules for absorption into the bloodstream. This 'enteric fermentation' produces hydrogen and carbon dioxide that an enzyme then combines to form methane, which the cattle then continuously burp.

Emissions on farms also arise from fertiliser and manure use in the form of both methane and nitrous oxide).

Methane has a shorter atmospheric lifespan than CO2, but is 30 times more effective at trapping heat over a 100-year timeframe.

Late last year, New Zealand's government confirmed plans to price agricultural methane emissions - 20 years after a similar measure was abandoned following strong opposition.

Water

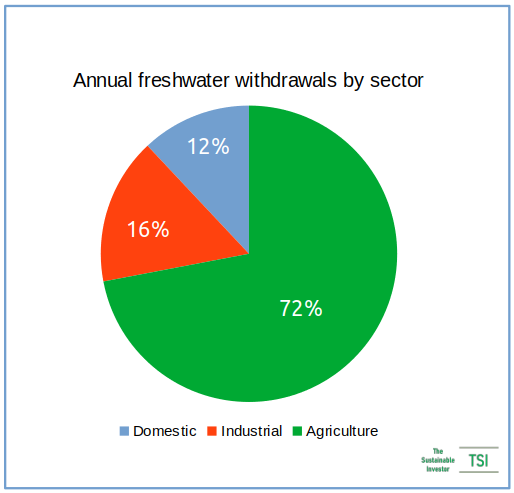

The second major environmental impact is water usage. Agriculture is by far and away the largest user of freshwater.

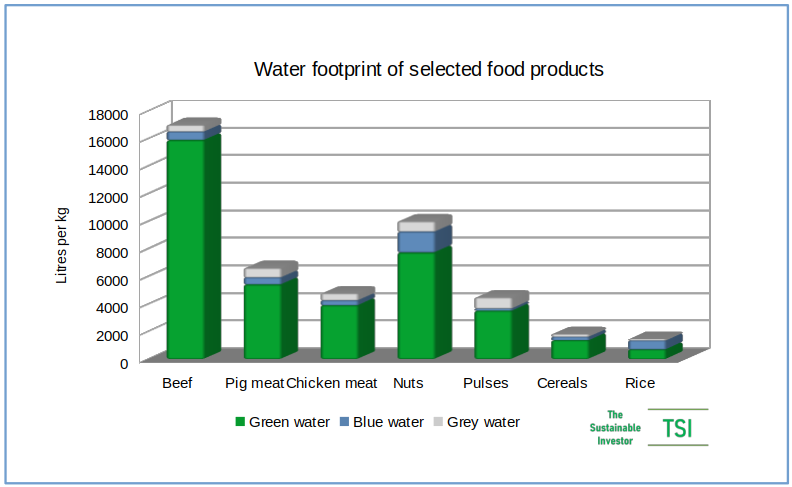

Meat production has a significantly higher overall water footprint that other agricultural produce.

Within beef production there are geographical variations in terms of the types and amount of feed used and associated water footprints. For example, almost 98 percent of beef production's total water footprint comes from their feed. Some studies estimate that the total water footprint of feed crops amounts to 20 percent of the water footprint of total crop production.

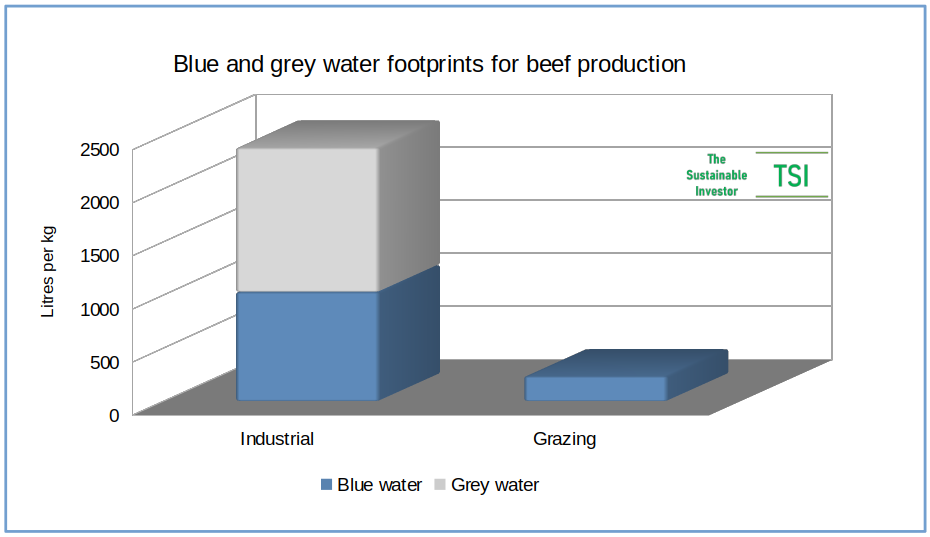

There are also differences between industrial beef production and open grazing. Industrial beef production has ten times the combined blue and grey water footprints of grazing.

Antibiotics

Globally it is estimated that 66 percent of all antibiotics are used in farm animals.

In addition to treating diseases in animals it is mainly used in sub-therapeutic levels in concentrated animal feed to promote growth, prevention of disease and in improving feed conversion efficiency. In the UK, 75 percent of farm antibiotic use is for group treatments, i.e. to groups of healthy animals. In Europe is is above 85 percent.

Overuse of antibiotics is a key way in which microbes can develop antimicrobial resistance (AMR). You can read more about this topic here 👇🏾

That means that agriculture is one of the most important areas for developing better stewardship. The FAIRR initiative (‘Farm Animal Investment Risk and Return’) was founded with the intention of driving change in the animal agriculture industry. Changes in the way that animals are reared can greatly reduce antibiotic consumption, for example through open grazing (so the animals are not in such close proximity to each other for extended periods) and in the absolute reduction in consumption.

Let's take a look at some innovations in how we feed cattle that can mitigate some of these impacts...

Minimising impact on the environment

Remember those burps?

The methane is produced by microbes (bacteria) in the rumen. In some cases, genetic traits can mean an animal has more or less of certain types of bacteria. RuminOmics is an EU-funded programme investigating the animal genome, gut microbiomes and links to the environmental impact of ruminant livestock production. Identifying the precise genetic profile of animals that have the right balance of microbes could lead to breeding to produce cattle that produce less methane.

Another approach is to add substances to feed to reduce that enteric fermentation process that we mentioned earlier. This can include adding calcium nitrate or even garlic to existing feeds. There are even possibilities from the ocean...

Back in 2018, researchers from UC Davis found that adding Asparagopsis taxiformis or red seaweed into cattle feed significantly reduced how much methane they were burping up. The addition of seaweed into a cow’s diet helps block methane production during enteric fermentation by suppressing the enzyme that combines hydrogen and carbon dioxide to combine. There are now commercial products available in a number of countries. Here is one such example, Bovaer, which claims to be able to reduce methane emissions from dairy cattle by 30 percent and up to 45 percent for beef cattle on average.

Similar methods are being explored to reduce emissions from other livestock, such as adding goat willow leaves into sheep diets, reducing levels of nitrous oxide, CO2 and ammonia in the urine of lambs.

Here is another feed alternative, but this time on dry land (and sometimes in the air). The largest class in the animal kingdom - insects.

Ynsect runs the world's largest vertical insect farm producing more than 1,000 tonnes of animal feed per year. They are just one example in a growing industry.

Many species of insects are high in protein and other nutrients, making them a nutritious food source for animals - In fact, even more nutritious than traditional animal feed such as soybeans and fish meal.

On top of that, insects can be raised using fewer resources than traditional animal feed, needing significantly less water and land than soybeans. Ynsect claim that their process uses 98 percent less land and 50 percent fewer resources than used for conventional livestock farming. Soybean has also been associated with deforestation whilst fish meal is problematic due to overfishing. Insect cultivation produces fewer GHG emissions and generate very little waste.

There are also potential costs savings as circularity can be built in. Insects can be raised on organic waste products such as food scraps and agricultural byproducts even from the farms themselves. They can also be used for a variety of animals, from chickens to cattle, and can be processed into different forms, such as powders or pellets, making them easy to transport and store. However scale means that at present they can be more expensive to produce overall. That may come down in time.

It is not necessarily a straight drop in as there may be allergies amongst livestock and even palatability issues as cattle get used to a new taste.

The logistics of feeding

In many farms, cattle can be dispersed throughout the farm's pastures when feeding and drinking water. There are a number of ways in which farmers can tend to their cattle remotely.

Drones can be used in a number of ways. They can be used to survey pastures and identify areas where grass has been over- or undergrazed. This can be helpful in deciding where to move cattle to ensure they have access to enough food.

Drones can also be used to dispense feed to cattle, saving time and resources compared with using trucks or tractor vehicle. They can also be used to monitor feed levels in troughs or other storage facilities. This can help farmers ensure they have enough feed on hand and avoid running out.

Another way of performing the feeding and watering task remotely is through the use of Internet of Things (IoT) devices.

IoT sensors can monitor both feed levels in silos and troughs dispensing the appropriate amount of feed at the right time, and water levels in watering tanks and other water sources. These sensors can provide real-time data on water usage and detect issues such as leaks or overflows.

IoT sensors can also be used to monitor environmental factors that can affect cattle health and feeding habits, such as temperature, humidity, and air quality.

The very large amounts of data that can be collected from IoT devices can be analysed to identify trends and patterns in feeding and watering habits.

This information can be used to optimise feeding schedules, potentially providing more precision and personalised feeding, which can improve health and productivity of the cattle.

But it is not just on the outside... ingestible IoT sensors can help farmers monitor the health of their livestock real time giving early warning signs of ill health.

This could all reduce the use of antibiotics over time.

Lateral thought

In considering what we feed cattle we can also potentially improve the efficiency of food production for human consumption.

Researchers from Aalto University in Finland, led by associate professor Matti Kummu examined how food and feed flows through the global food production system. They concluded that replacing livestock and aquaculture feed that could be used for human consumption with food system by-products and residues could free up enough food to feed an additional one billion people!

The changes proposed could redirect between 10-26% of total cereal production and approximately 11% of current seafood supply to human use. This would represent as much as 15% of current food supply protein content and up to 13% of caloric content.

You can read more about that here 👇🏾

Conclusion

There are real concerns about our ability to feed the world, while at the same time trying to reduce the impacts on our natural world. Agriculture sits at the intersection of a number of UN Sustainable Development Goals. Agriculture, forestry and other land use generates 22 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions and utilises 72 percent of global freshwater supplies. Meat is responsible for a big part of that impact and how cattle are fed is significant. It is also an important battleground in the fight against antimicrobial resistance as antibiotics have been historically overused in concentrated animal feed.

Reforming agriculture is going to require massive social and economic change and disruption to production methods, to supply chains and to employment. Innovation in feeding cattle covers a number of areas including the logistics of feeding, improving the health of cattle and minimising their impact on the environment.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.