All that glitters is not gold

Gold Mining: as well as being the largest global artisanal mining activity, also faces a number of sustainability challenges. One is where it comes from, and another is how it's processed.

Summary: Gold Mining: as well as being the largest global artisanal mining activity, also faces a number of sustainability challenges. One is where it comes from, and another is how it's processed. And of course, you have the wild card question of why we mine it, or more strictly why we mine so much of it.

Why this is important: Gold mining is a good example of some of the challenges we face in ensuring that our mining is sustainable. While the scale of artisanal mining might seem small, until we find ways to formalise it, the existence of criminal and corrupt gangs has the potential to destabilise the supply chains that service our wider society. The solutions need to be local. This adds an extra layer of complexity for investors and activists.

The big theme: As we frequently remind people, as we move toward more sustainable business models, we will need mining more than ever. It's an industry where simple solutions are harder to find, which means investors and sustainability professionals need to dig down into the details.

The Detail

How big is the global gold mining industry?

The global gold mining industry is worth c. US$200bn, with annual production being close to 3,500 tonnes pa. While the industry used to be dominated by production from countries such as South Africa and Australia, there has been significant geographical diversification of mined gold supply over recent decades. Now China and Russia are the world’s largest producers, and within Africa, Ghana now has higher production than South Africa.

To start to gather some answers as to how gold mining can be made sustainable, especially in the context of artisan mining, we again have turned to Rob Karpati from The Blended Capital Group. This is the second blog that Rob has written for us on this topic.

This is the last "setting the scene" blog, next up we will dig some more into solutions. Over to you Rob.

Artisanal gold mining - challenges and opportunities

Artisanal gold mining is the largest Artisanal Scale (ASM) sub-sector. Of c. 45 million artisanal miners, 15-20 million are gold miners across 80+ countries, producing c. 20% of globally mined gold. Including families of miners, there are 100 million people directly supported by ASM gold.

Artisanal scale gold mining (ASGM) is different from large scale mining, taking place at or directly below ground-level. Work is manual, and supply chain relationships are informal, without predictability and vulnerable to corruption at the front-end of long value chains. There are environmental concerns, notably including mercury contamination.

Artisanal gold mining is spread across the world, including Latin America (Honduras, Nicaragua, Columbia, Ecuador, & Peru), Africa (Suriname, Mauritania, Mali, Senegal, Guinea, Burkina Faso, Cote d'Ivoire, Ghana, DRC, Uganda, Tanzania, and South Africa) and Asia (mainly Indonesia and the Philippines).

ASGM is largely informal. Miners lack financing that would enable the ability to self-organize. At the front-end of value chains, they are vulnerable to corruption, safety issues, human rights abuses, and poverty traps with no clear exit. There is very limited data outlining realities, making invisibility a challenge where broader value chains through to end consumers do not have clear views of upstream realities.

Back to Rob ....

It is important to remember that circumstances vary by place.

There are a few countries where ASGM is legal, and where miners are extensions of neighbouring communities, with individuals seeking to improve their circumstances through mining.

But, it's more normal for ASM to be considered an illegal activity, which increases vulnerability, as corrupt actors and intermediate value chain players claim economic shares without adding value. For instance, in Colombia – ASGM is largely deemed illegal, which has opened the door for organised crime to dominate the sector with 350K miners, given the basic reality that gold is more lucrative than cocaine.

More recently, in Uganda in 2022 there was an announcement that $13 trillion in gold reserves were discovered in the country. Without strong central governance or a focus on formalised ASGM, there is the potential for a gold rush that brings a variety of criminal players into the country given the massive potential wealth. What will this look like for miners themselves?

Lack of legal recognition makes it impractical for most miners to gain formal land rights. ASGM often takes place on the land concessions of large mining companies, where they are seen as squatters.

The result of this reality opens the door to child labor, forced labor and sexual violence where female miners are at-risk. Although there are significant endemic issues across the sector, it is important to remember that realities vary by location, given that ASM in general reflects socio-economic contexts of countries where it takes place.

Important organisational voices highlight the need for responsible ASGM and locally-appropiate formalisation, including the Swiss Better Gold Association and PlanetGold. There are also standards on responsible formalisation, including the Fairmined Standard, but take-up has been limited, with most miners continuing to operate informally.

Editor's note - there are some interesting debates on formalisation. For instance Robles, Verbrugge & Geenen found that in the Philippines that

"formalisation efforts need to take into account the needs and preferences of those involved; and that these preferences do not always align with mainstream notions of decent work"

And Hilson, Bartles & Hu suggest that one reason why Ghana's formalisation programme, which has been running for four decades now, might not be working because:

"the country’s ASM formalization strategy is highly-centralized."

Both of these pieces of research support Rob's argument that the solution is local.

Back to Rob again ....

Environmental concerns mainly centre around mercury, which is used to extract gold from gold-containing materials.

Mercury is toxic, entering water and soil which neighbouring communities rely on, while also impacting the health of directly exposed miners.

Editor's note (again - sorry Rob ) - the mercury issue is not a new one. The extraction methods that some gold mining operations use today are not drastically different from processes that miners employed in the California gold rush in the mid-1800s. And we see history repeating itself in places like the Peruvian Amazon, where small-scale gold mining threatens to leave behind long-lasting social, economic and environmental consequences.

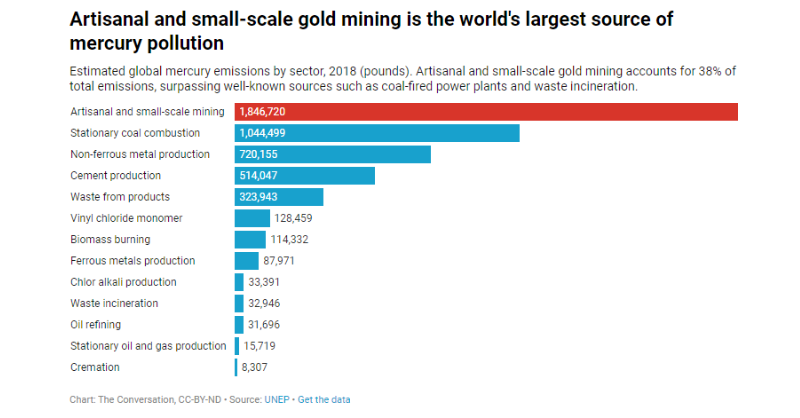

According to Gerson, Wadle & Parham, artisanal and small-scale gold mining is the world's largest source of mercury pollution.

Miners use mercury because it is the cheapest, easiest and fastest way to mine gold, and because they are often unaware of its risks or ways of avoiding them. Some miners, such as the Aurelsa cooperative in Peru, have managed to save enough money to upgrade to the cyanide leaching technique used by large-scale mining firms, which as the recent Colorado mining disaster shows, carries its own suite of hazards.

Back to Rob (this is the last interruption I promise) ...

Mining also has broader environmental impacts, notably deforestation and soil degradation. For instance, the Amazon region of Brazil has experienced significant deforestation from gold mining. Here, it is important to distinguish illegal mining from traditional artisanal mining, with much of what happens in Brazil being illegal.

So, what can be done: the big picture

The key approaches in gold mining mirror what we believe is generally appropriate across other types of ASM.

• A standards and best-practices driven investment marketplace can target opportunities for locally-apt formalisation. Flexible frameworks are critical for formalisation, where local cultures and socio-economic realities are the basis for approaches that make sense. Formalisation is also inherently in the context of broader sustainable development – value for miners can catalyze broader regional value. Although standards and best practices need to be globally generic, targeting opportunities flexibly is essential for driving locally fit for purpose solutions. We strongly support the work of the UN Mining 2030 Investor Commission

• As an investment marketplace is set-up, now is the time to target impactful projects, learning and informing broader long-term standards. Pilot projects are critical. Plus, legal frameworks outlining rights of artisanal miners are necessary. The fact that the sector is deemed illegal is a barrier to formalisation. Clarity of artisanal miners’ rights provides clarity for projects that target impact.

In conclusion, ASGM is a huge sector, with uneven realities across countries. Opportunities for formalization need to be locally-targeted given different circumstances across regions. Effective formalisation combined with legal clarity can enable extreme shifts in the dignity and productivity of artisanal gold miners while also contributing toward broader sustainable development and respect for human rights.

One last thought to leave you with.

Around 7% of the gold purchased globally each year is used for industry, technology or medicine. The rest winds up in bank vaults and jewellery shops. Nearly one-quarter of annual gold demand is supplied through recycling, making it one of the world’s most recycled materials. The recycling process uses no mercury and has less than 1% of the water and carbon footprint of mined gold. Given how much of the world's gold is as an "investment", is there a different way to think about this challenge.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.