Ooh ah, just a little bit - transition is a series of steps

The thing with sustainability transitions is that whilst there is a starting point, there is no end point. The world is a continually changing place and we are continually transitioning.

Summary: Transition is a series of steps: stages, individual action & nudges (and their limitations). Training for a triathlon and transitioning in sustainability have many parallels. There are barriers to change: nirvana fallacy, bite-sized content and binaries and when balanced journalism causes an imbalance. Small steps and nudges can be effective. Examples discussed include preventing conflicts between cyclists and cars, how 'superpower satsumas' helped kids to eat more healthily, picking no sugar drinks options at McDonald's, wasting less food through measurement, and using less 'small power'.

Why this is important: Perfect can be the enemy of good. However, we can't teleport to the ideal. We need to make the right sequential moves to get there.

The big theme: The thing with sustainability transitions is that whilst there is a starting point, there is no end point. The world is a continually changing place and we are continually transitioning. Getting from walking to completing a triathlon doesn't happen overnight. The same is true in sustainability. It's a series of steps.

The details

The thing with sustainability transitions is that whilst there is a starting point, there is no end point. The world is a continually changing place and we are continually transitioning.

In this blog I shall discuss:

- Training for a triathlon and transitioning in sustainability

- Transition is a series of steps: stages, individual action and nudges

- Some barriers to change: nirvana fallacy, bite-sized content and binaries and when balanced journalism causes an imbalance

- Some examples of where nudges have been effective: preventing conflicts between cyclists and cars, encouraging kids to eat more healthily in schools, picking no sugar drinks options at McDonald's, wasting less food and using less 'small power'.

Triathlon and transition

At school I played a lot of sport which continued when I went to university and into my twenties when I played football regularly for my employer at the time, Price Waterhouse. Then in my thirties, quite frankly I adopted a shameful disregard for my own health. As my fortieth birthday approached I found myself at the heaviest and most unfit I had ever been in my life. I decided that enough was enough and I would start hitting the gym. In order to push myself to go, I decided to put a marker in the sand, a goal to aim for, a target with a deadline: I signed up for a triathlon.

I picked a triathlon because it was well beyond my capability at the time. I had never really run further than one km in a running race, had only cycled to school and back (around three km) and effectively I couldn't swim. Or rather I could shift an awful lot of water in multiple directions for about 15 metres.

Just under nine months later and this was me, competing in the Blenheim Palace Triathlon (sprint distance) with one of my friends. I am on the front bike slightly ahead of him.

So how did I get there? It certainly wasn't overnight. I didn't flick a switch and suddenly I was a triathlete. I broke down my transition into a series of manageable steps. I needed to learn to swim properly, get my running distance up to 5 km and my cycling distance up to 20 km with speed over hills. And get my transition (no pun intended) efficient. And those steps needed to be broken down into smaller steps. For swimming, getting my body positioning right, my breathing effective (or in my case, actually breathing at all!) and developing my 'catch'.

Getting those small steps right added up to me being able to complete that 2014 triathlon and subsequent ones leading to me eventually entering longer distance races including swimming 1.9 km - my 2013 self would have laughed hysterically at the thought of swimming that distance.

That series of steps continues. You can ALWAYS improve. So yes, whilst I am 'slightly ahead' of my friend, he is about to lap me. Yes. Lap me on a 3-lap course.

So transition is a series of steps. That is the provocation in the title of this blog. But what does that mean? I see three different areas:

- Stages: To get from where we are now to where we want to be, there may be a number of intermediary stages. For example, with urban transportation, electrified mass transit and/or 20-minute neighbourhoods may be the ultimate goal, but to cater for existing car-centric urban design during that transition, mass rollout of EVs may be needed. Those steps can take many years requiring investment decisions with long payoffs. The transition to green steel is an example acting as a trailblazer for other hard to abate sectors.

- Individuals: Small incremental steps actively taken by individuals to change their own behaviour and improve the sustainability of their footprint whether that is environmentally or socially; and

- Nudges: Small, subtle changes to the environment or infrastructure influencing people's decisions and behaviour, often without them consciously realising it.

Transitional steps can face a number of barriers.

As Voltaire wrote in La Bégueule that "Le mieux est l'ennemi du bien" which roughly translates as "the perfect is the enemy of the good" - the 'nirvana fallacy'. This is where a solution is dismissed, particularly a stage in a transition because it has some drawbacks.

As content length is getting shorter it forces debates to be binary - something is either good or bad. That also tends to encourage the hunt for the 'silver bullet' solution or the one-size-fits-all.

In addition the trend of mainstream journalism to avoid bias has, in some cases, unintentionally presents scientifically compelling conclusions as open debates (we cover that and the 'binary' issue in more detail later).

These have the effect of presenting uncertainty and hesitation in the minds of individuals and organisations - 'too many issues, it won't work, let's not do it.'

However, there will always be trade-offs. That doesn't mean something isn't a valid step to take on the journey.

For example, a deposit return scheme to encourage recycling of drinks containers is being introduced in the UK. The aim is ultimately to minimise the amount of plastic waste in particular ending up in landfill or being incinerated and causing harm to the environment. Plastic is often cited as being problematic, however how we use containers is as much a part of the problem as the materials themselves. A lifecycle assessment of drinks containers from Southampton University found that whilst glass and recycled glass bottles are more impactful on the environment than other containers, ALL containers had some impact. As the Southampton study's lead, Alice Brock commented "society needs to move away from single-use beverage packaging in order to reduce environmental harm and embrace the regular everyday use of reusable containers as standard practice." Intelligent dispensing and refillable solutions both in private and public areas are clearly going to be supportive of that. Behaviourally, a recycling scheme is a good transitional step to take.

Another example of how small steps can lead to larger sustainability transitions is through the integration of green spaces, such as parks, gardens, and wetlands, into urban areas. There are many benefits including increasing biodiversity, improved air and water quality, a reduction in the heat island effect and enhancing community spirit and overall well-being. By starting small, for example by planting a community garden or creating a green roof on a building, individuals and organisations can demonstrate the benefits, inspire others and that can potentially lead to larger development. The Oasis School Yards projects in Paris developed existing school playgrounds acting as green hubs, reducing the heat island effect of the city, improving flood resilience and encouraged social resilience as community and schools come together.

The second bullet, 'steps that individuals can take', can also sometimes fall foul of the nirvana fallacy as being 'immaterial'. In his book "How Bad are Bananas?: The Carbon Footprint of Everything" Mike Berners-Lee points out that a whole year's worth of watching TV may be similar to driving a car 500 miles for an individual. That represents about 6 weeks of the average person's daily commute in Germany. So an individual's footprint from watching TV doesn't seem that much. However whilst the individual contribution may be small, the number of individuals is big and so the collective impact could be huge. This is an important point across sustainability transitions.

Small steps can also be a way of engaging and empowering individuals, communities, and organisations. By encouraging people to take action in their own lives and communities, sustainability transitions can become a bottom-up process, rather than a top-down one. This can be especially important for creating buy-in and commitment from individuals, who may be more likely to participate in the transition if they feel that they have a stake in it. One such example is in Germany where IBC Solar partnered with EUECO to develop a digital platform to encourage citizen participation in German solar parks and the generation of green energy.

Where solutions to improve sustainability are behavioural, often wholesale changes are so overwhelming as to be rejected outright. Professor Alex Edmans, in a lecture for the Gresham Institute talked about status quo stemming from inertia (it takes effort to make a decision) and conformity bias (taking cues from others’ actions even if uninformative).

Small changes can 'nudge' us towards a desired behaviour. This is our third bullet and the main focus of this blog. A 2008 book by behavioural economist Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, "Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness" first introduced 'nudge theory' into the mainstream. Whilst there has been some debate about their effectiveness overall, there are other examples where small nudges in behaviour can help us be more sustainable, particularly in food and health-related areas. Why do some nudges work and others don't? Evidence is mixed, but it may be that default options can be in some cases more persuasive than simply providing information. We shall look at one example later.

We will discuss some more examples in this blog, including smart signs to prevent conflicts between cyclists and cars, positioning of fruit and veg to encourage children to eat healthily, McDonald's menu positioning, meal boxes and a plug socket that tells you when the energy you are using is green.

Before that, let's look at some of the barriers to change that often get overlooked, in addition to the nirvana fallacy mentioned earlier.

Bite-size content leads to binaries

Around 1439, Johannes Gutenberg developed a process for mass-producing printed books. Before the printing press, books were largely produced in Latin by scribes in monasteries and so not readily available. Now you could make many more books than could ever have been made by hand. So ideas could be shared and accepted by many more people and that meant broader collaboration between academics and practitioners.

The amount of content being produced has grown dramatically since then, and is forecast to grow at an exponential rate. In 2018, IDC estimated that 463 exabytes of data will be created every day by 2025 (one exabyte is the equivalent of the storage capacity of 15.6 million of my phones!).

The Internet and social media are the modern printing press, enabling information sharing and collaboration on a huge scale.

However, to achieve that scale, content has become bite sized – 60 second Instagram Reels, 3-minute TikTok videos, 280-character tweets. The impact of that has been to reduce often nuanced ideas or solutions into binaries – it’s either good or it’s bad or there is only one solution, a one size fits all. Disciplines and thinking have become quite siloed, in many ways the antithesis of what happened in the renaissance where art and science were regularly combined to arrive at a solution. Just look at what people like Leonardo da Vinci achieved.

The truth of the matter is that some solutions are appropriate in some situations but not in others. Things are interconnected and so when we think about the challenges that achieving the UN’s Sustainable development goals are bringing, broad collaboration is critical. We need to think laterally and holistically. Let me give you just one example. Researchers from the Universities of Virginia and Maryland looked at scenarios heavily reliant on net emissions reduction technologies and they predicted that given competing demands for energy, water and land from bioenergy crops, food prices in the global south could jump 5x from 2010 levels by 2035.

Think about that for a moment. An endeavour designed to address Sustainable development goal 13 (Climate action) could have an adverse impact on Sustainable Development Goal 2 (zero hunger). We saw that impact in India in 2021 where the country’s grain-based ethanol targets were causing food security concerns.

It is hard to capture that nuance when content is short. So short. It is a key reason why we opted to produce longer form blogs as well as our shorter form 'Perspectives' to enable that nuanced debate and go into a bit more depth.

When balance causes imbalance.

Bias in news reporting has long been thought of as something to avoid. Balance and fairness are central to objective journalism, striving for "accuracy and truth in reporting and not slant a story so a reader draws the reporter's desired conclusion." (ONAethics)

However, this can lead to some unintended consequences.

Researchers from Towson University and the University of Wisconsin, studied more than 200 articles published between 2018 and 2020 in 29 different U.S. newspapers, comparing coverage of two issues: the need to reduce food waste and the need to shift to a more plant-based diet. Despite there being strong consensus amongst scientists on the latter issue, newspapers were covering it as an open debate.

The researchers compared this with media coverage of human-caused climate change ten years ago where a similar open debate approach was taken with "climate deniers quoted in the media often [having] financial ties to industries that were trying to avoid efforts to address climate change." More recently public perception has driven that 'openness' of the debate down.

If there is a delay in scientific consensus being accepted by the general public effectively creating doubt through the presentation of an issue as a more open debate than it is, this could further delay acceptance of a problem and the move to the next step: enacting solutions.

The above barriers are not insurmountable. They just make it harder. Let's now look at some examples of nudges that have been effective, as a starting point.

Smart signs reduce conflicts between drivers and cyclists

While many of the things we need to do to decarbonise our built environment are big (heat pumps, building insulation, EV charging etc) it’s easy to forget that many are also small and local. These often use smart technology in clever ways, making moving around our cities easier and safer.

Solar-powered LED warning signs have been installed by Glasgow City Council to alert drivers to the presence of cyclists following on from a successful pilot. The system trial, at the junction of Berkeley Street and Claremont Street, saw a fall in the percentage of “conflicts” between drivers and cyclists.

The council has used smart sensor technology on previous projects and the roll-out will focus on locations where sight lines are sub-optimal, for example at side junctions or building entrances.

The use of renewable energy to generate the electricity helps to reduce roll out costs.

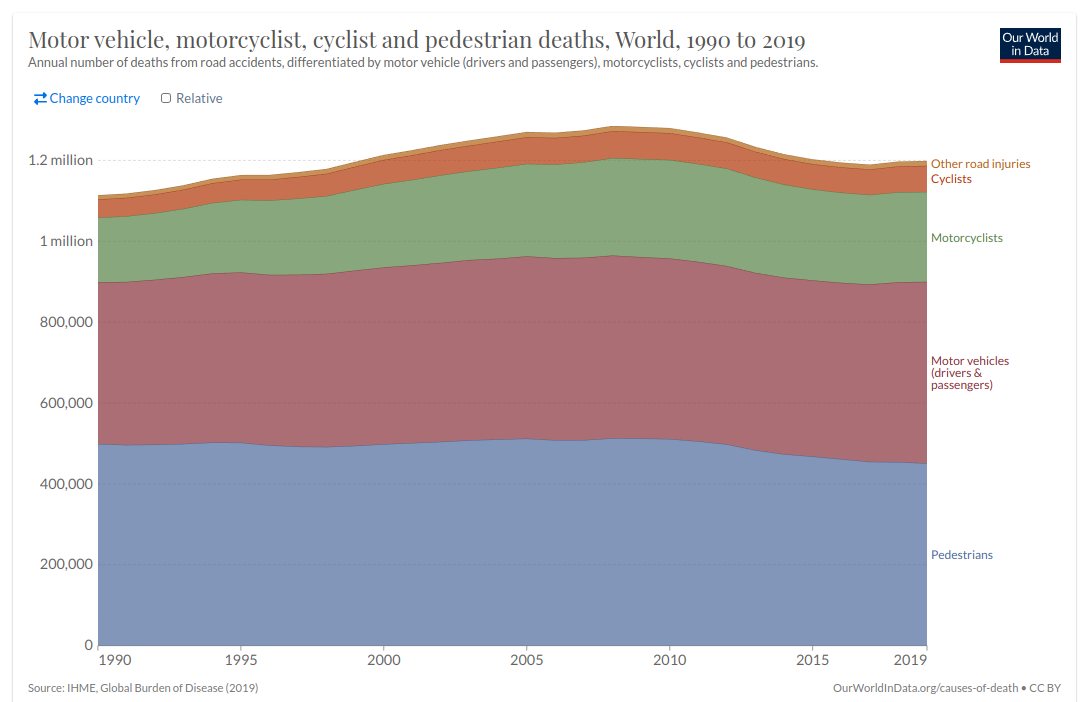

Why is this important? More than half of all road traffic accidents involve vulnerable road users, i.e. pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists. Globally in 2019, there were more than 450,000 pedestrians, almost 65,000 cyclists and over 222,000 motorcyclists killed in road traffic accidents. Middle-income countries make up more than 80% of those vulnerable road user deaths with 8% from low-income (the latter due to the greatly reduced road infrastructure). Road traffic crashes cost most countries three percent of their GDP.

Fruit first fosters fine fettle feeding

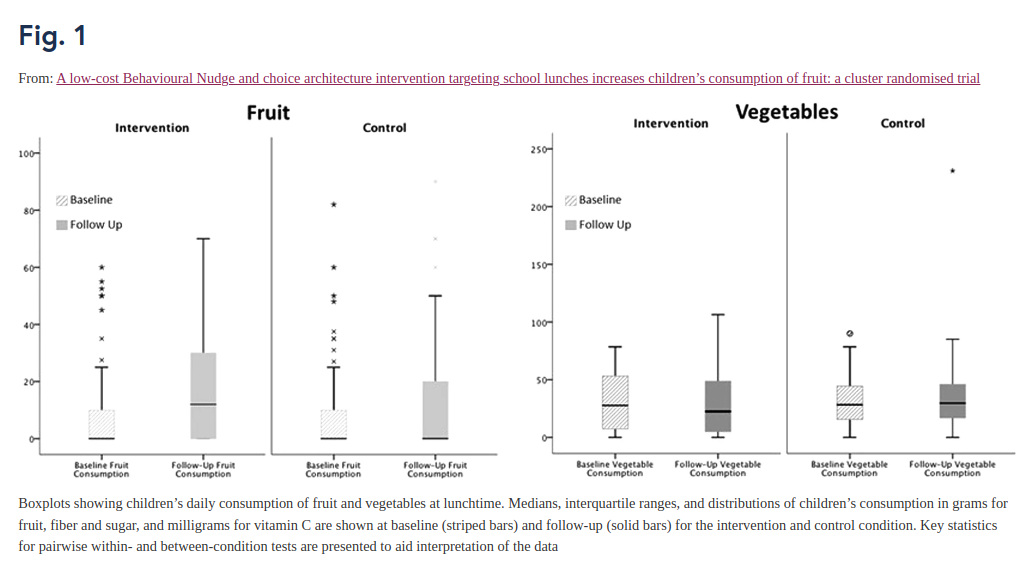

Researchers from Bangor University, Wales, collected data from four primary schools over a two day period on pupil's consumption, in particular that of fruit and vegetables. Then some changes were made to how different kinds of food were presented to the children (in some of the schools), for example improving the positioning and serving of fruit and making the labelling more attractive.

Examples of the more attractive labelling included given the produce different names such as “Dinosaur Tree Broccoli”, “Anti Sneeze Peas”, and “Superpower Satsumas”.

With the changes in place for three weeks, consumption data was then collected, again over a two day period and the results compared.

The researchers found that for the schools where changes were made, there were significant increases in the amount of fruit, vitamin C, and fibre consumed. Given that there were no significant changes seen in the control group, the increases in fruit consumption were most likely due to the changes that were made.

In the group where changes were made, 46.5 percent of children ate more fruit compared with 18.9 percent in the control group and only 9.3 percent ate less fruit compared with 17.8 percent in the control group.

Interestingly, there was no change in vegetable consumption in either group. Superpower Satsumas 1 - Dinosaur Tree Broccoli 0.

Nudging Coke Zero to #1

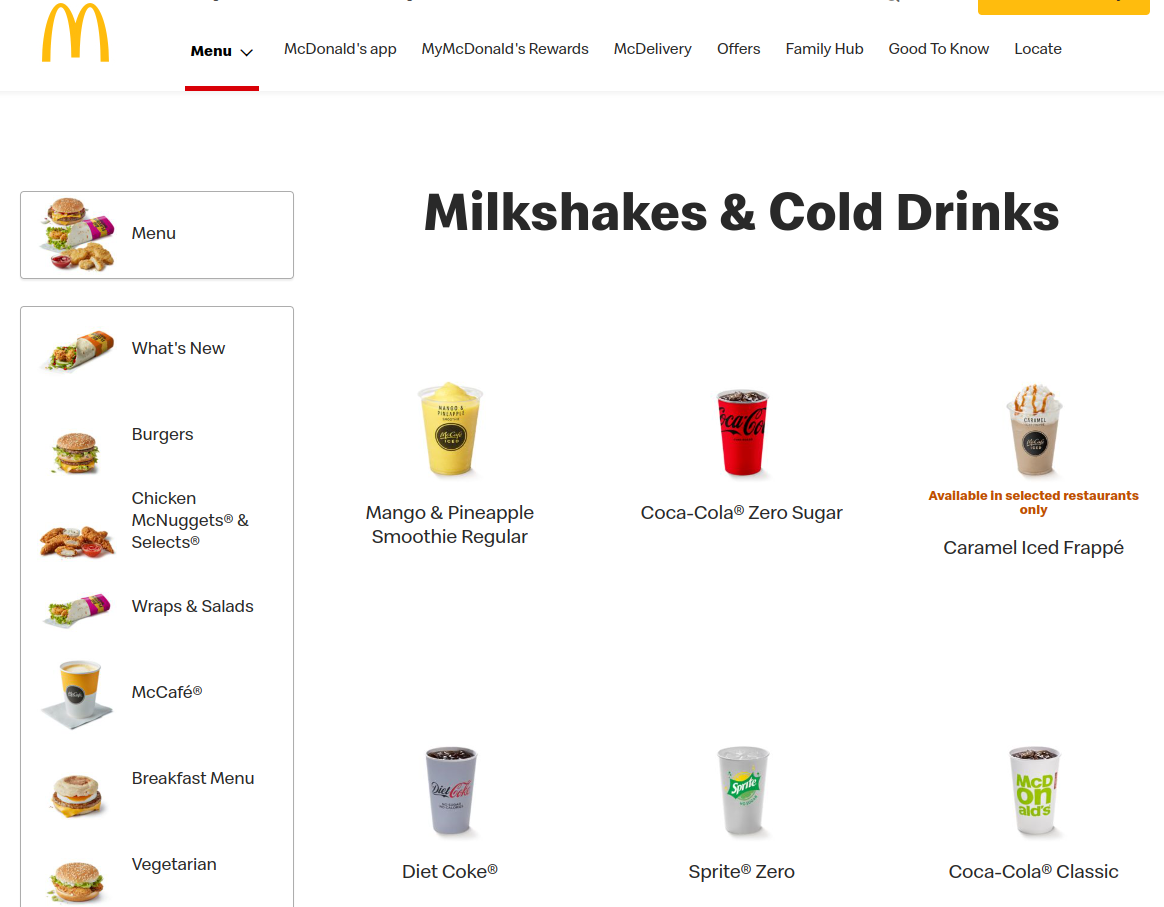

A Manchester Metropolitan University 12-week study found that by moving the Coke Zero icon on digital menus of more than 500 stores from the third to first position, while moving the regular Coca-Cola icon from first to last, led to increased sales of Coke Zero by 30% and decreased sales of Coca-Cola by 7%.

Here is a screenshot of the McDonald's online menu today:

Interesting to note that 'Coca-Cola Classic' is pictured on the menu in a 'McDonald's' cup, further providing that branding distance. Those of us of a certain age will remember the refrain from servers at McDonald's "sorry, we have McDonald's Cola."

Finally, the rebranding of Coke's zero sugar product from 'Coke Zero' (a very distinct brand) to the current 'Coca-Cola No Sugar' which has been made to look very similar to 'Coca-Cola Original Taste' or classic Coke. Very subtle nudge, but moving towards normalising the no sugar version.

From a sustainability perspective, this is one area that Coca-Cola is addressing. Clearly there is much further for the company to go, particularly with regards the proliferation of single-use plastic in their product set, but small steps are being made, for example tethering caps to bottles to increase the likelihood that they will be recycled along with the bottle.

Reducing food waste through measurement

A study across six countries (UK, Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, Canada and the US) found that the use of meal boxes reduced total meal waste by 38 percent compared with meals cooked with store-bought ingredients. The meal boxes contain precisely measured ingredients and recipes. In particular the amount of food left in pots and pans was reduced by 34 percent. Interestingly the amount of food wasted as leftovers on plates was increased by 15% with meal box dinners.

The amount of household food waste may surprise you. It is much higher than retail food waste. According to the UNEP’s Food Waste Index 2021 report, the estimated household food waste per capita is 59kg in the United States, 77kg in the UK (that’s one of me!), 81kg in Sweden, 64kg in China and 102kg in Australia.

Despite this waste, the World Food Programme estimates that 828 million people go to bed hungry every night across the globe and even in countries like the UK, it is estimated that 4.7 million adults struggle to afford to eat every day. This is a huge social problem that has knock on effects to education, health and ultimately productivity. Environmentally it is also important. The UNEP estimates that between eight and ten percent of global GHG emissions are associated with food that is not consumed and ends up in landfills.

There are a number of problems to solve. Firstly, reducing the amount of ingredients that are not used - this is essentially the key finding from the study. Meal boxes do this for the consumer but the consumer can also take control. More accurate measurement or using frozen ingredients, either shop bought or prepped (for example chopping and freezing onions), makes it easier to use only the exact amount needed when cooking.

Secondly, the issue of food left on the plate can be alleviated by a combination of portion control (behavioural) and having adequate food storage (I remember Korea’s LocknLock from my Asia days).

Thirdly, stopping the food waste getting to landfill where it can release GHGs. Home composting (particularly with aerobic digesters) or municipal composting (particularly with some form of methane capture) will typically have a lower GHG footprint than landfill. Social enterprises such as The Felix Project collect surplus food from retail stores including supermarkets and turn it into pre-prepared meals for those in need.

Near expiry date reselling apps such as Too Good To Go provide consumers with the ability to buy food that would otherwise be thrown out by retail stores at heavily discounted prices. Some food sharing apps such as Olio also allow individuals to share their surplus food, subtly nudging behaviour to accept that food is still very much edible!

Plug socket tells you when it's green to go

Pre-pandemic I was living in a small rented apartment in London and paying for my electricity via a fixed direct debit. I managed to cut my monthly payment by 12.5 percent by making two simple changes:

- Turning off appliances at the plug socket when not using them; and

- Taking my hot water boiler off the timer and instead switching it off for three days at a time. The tank was big enough and lagged enough to provide me with enough hot water for showers for those 'off' days.

These were as high tech as my interventions got back then.

UK start-up Measureable.energy has combined smart sockets ('m.e. Power Sockets'), machine learning and a cloud-based platform to try and help businesses and individuals reduce 'small power' usage (from plugged in appliances) - and arguably wastage! Small power often exceeds 40 percent of total electricity usage in commercial office buildings.

The m.e Power Sockets glow green, amber or red according to the ratio of renewable to fossil-based energy being used.

(Source: BBC News)

The small indicator lights act as nudges but longer term the behaviour should hopefully become ingrained. I always turn off my appliances from standby without even thinking about it now.

Don't cross the streams!

Finishing off with one of the more famous nudge examples: The Schiphol Airport urinal fly.

Although bees were put in Victorian urinals (a joke on the Latin 'apis'), and there have been various other patented 'targets' over the years, the most famous is the idea to put images of flies into urinals at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam in the early 1990s by airport manager Aad Keiboom and cleaning department manager Jos Van Bedaf. The aim was to reduce 'spillage' and ultimately reduce cleaning costs.

But are men really that simple-minded? Yes we are. We can't resist aiming for a target.

Kieboom estimates that the flies led to around eight percent savings in cleaning costs.

Flies can now be found on urinals from JFK Airport in New York to Maharana Pratap Airport in Udaipur.

There are even gaming urinals. Sega has developed interactive urinals that provide a choice of mini-games all designed to 'hone the flow.'

Whilst 'targets' such as the Schiphol urinal fly can help prevent urine spillage and the resulting cleaning costs, that urine is still going somewhere - ultimately to a waste water treatment plant. We have seen to devastating effect what can happen when such plants are overburdened, particularly if they have been subject to underinvestment. Recent flooding, operational failures and under-staffing at Jackson, Mississippi’s primary water treatment plant, combined with decades-long infrastructure decay, resulted in an indefinite failure in the supply of safe tap water to Jackson’s 180,000 residents.

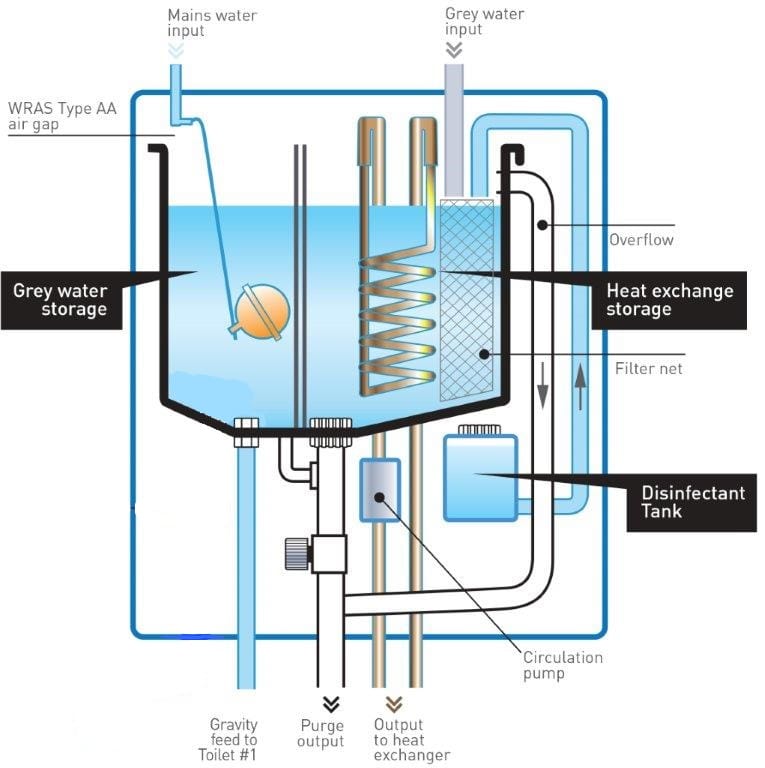

Reducing the burden on treatment facilities, and hence reducing the need for investment, can also come from the commercialisation of grey water systems where water is collected and reused from showers and sinks in, for example, toilet flushes where the water does not need to be potable. These can be commercial or residential and are being explored in water stressed countries such as India. They can also be used for garden irrigation and, with the right local treatment technologies, for agricultural irrigation too. In addition the heat can also be recovered from waste water in a grey water system, referred to as a greywater recycling heat recovery system.

Scaling up the availability of Urine-diverting toilets which have a urine collection basin at the front of the toilet bowl, draining to a separate tank from the solid waste can greatly reduce the water required for flushing. A key advantage is their applicability globally in both with dried faeces being used in agriculture post composting - composting toilets are another alternative here. Urine also requires far less treatment, thereby reducing the stress on treatment plants.

Once installed, these are an example of a default option, changing behaviour subtly without the user being inconvenienced or having to change their behaviour consciously.

Conclusion

Beyond consumer health, nudges could also be used to inform strategies aiming to encourage people to make more environmentally-sound choices. Whether that’s charging slightly more for products which involve single-use plastics (such as surcharges on disposable coffee cups), making sustainably sourced clothing a social status symbol, or making it more difficult for people to run non-electric vehicles, there is plenty of untapped opportunity in this area.

Small nudges to take the effort out of behavioural decisions could be one of the small steps that will make up our transition to a more sustainable existence.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.