Minimising cost overruns - part 3

Cost over runs not only destroy project economics, they also taint future similar projects with the cost 'blow out' brush. A technique known as Reference Classes can help, but we need to work together to make it useful.

While it might seem intuitively obvious that cost overruns are bad for investments, the scale of just how bad is frequently under estimated. Cost overruns not only destroy project economics, they also taint future similar projects with the cost 'blow out' brush. This could be a massive issue for the sustainability transitions. We know we need to invest a mind blowing amount of capital - $9.2 trillion pa is one fairly reasonable estimate. So, good project management will be critical.

Choosing the 'right' project is not just about what the spreadsheet tells us, or even what social/environmental outcomes the investment promises. Research tells us that certain types of projects are more prone to cost and time overruns.

There are techniques that we can use that help us make better estimates of project cost and timescale. In an earlier blog we talked about the approach used by (among others) the architect Frank Gehry.

Today we want to talk about Reference Classes - or put simply, identifying which types of projects give us a good base line for how much our particular project might cost, and how long it might take to build.

We want our sustainability projects to be financially and socially successful. So, we need to understand the reasons behind cost overruns. But we also need to contribute to the wider effort to build meaningful data sets - analysis that can help future sustainability professionals avoid the mistakes of the past.

The details

Summary of a research report published in ScienceDirect:

Planning and constructing large infrastructure projects, such as bridges, tunnels, public buildings, and power plants, are challenging tasks and often lead to cost and schedule overruns. Megaprojects are especially prone to these risks, as they are large in size, complex in nature, and highly unpredictable.

One of the key cognitive drivers behind poor cost estimation is 'strategic misrepresentation'. Under this, project promoters overestimate benefits and underestimate costs, with the goal of reaching project approval and funding. And once they have funding, it's hard for decision makers to reverse course.

One possible solution to this is to adapt what Kahneman and Tversky called an 'outside view'. Instead of thinking of our project as unique (an inside view), we instead look (outside) for projects that have already been completed that are similar to ours. Note - we are not looking for projects that are exactly the same, we just want them to have similar characteristics.

As Rebekka Baerenbold says in her research paper ...

The class must be broad enough, i.e., include enough cases, to be statistically meaningful but narrow enough to be truly comparable with the specific project.

Before thinking about some of the practical issues that using reference classes raise, it's worth reinforcing why, from a financial perspective, this is a big deal.

Poor cost estimation can destroy investment economics

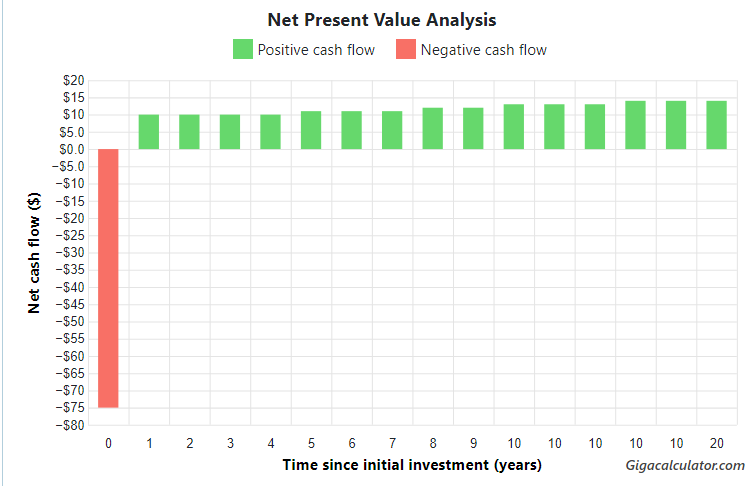

Let's imagine we have a simple investment opportunity that costs us $75m to build (construction takes just 1 year), and that gives us a revenue stream of $10m pa for 15 year's, growing at 3% pa. And just to make it simple, at the end of the 15 years the investment has no value. All of this data comes from the project promotor. Our cost of capital is 7%.

This could for instance be a remote renewable electricity generation plant, or a methane reduction add on to our existing chemical plant.

This looks a good investment, giving us a Net Present Value (NPV) of $30m. With an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of over 12%. So, obviously we build it - yes? Well maybe.

Let's now assume that our reference class analysis shows that projects of this type, on average cost twice the initial estimate (yes, I know it doesn't quite work this way, but I am looking to illustrate a point). If we re-run the numbers now, we get a negative NPV ( minus $45m), with an IRR of only 2%.

From a financial perspective, if the project only turned out to be 'average' it's much more marginal than the initial project promotor estimates first suggested. And it would probably need some sort of financial support to make it viable.

Using reference classes could have saved us from a poor investment choice.

Practical issues in applying Reference Classes

From a project sponsor/funder perspective, using an reference class/outside view can be really powerful.

But by now I sure you have spotted an obvious challenge (or more strictly challenges). First, and most importantly, we need better data on the cost and build time performance of historic projects. And the data needs to be more standardised - we need a probability distribution of project costs.

We must make it as simple as possible for project promotors and funders to identify which historic projects best make up their reference class.

And we need to test the reference class approach. We know it works in some situations (defence spending and some construction projects), but we need to check where it works best, and where it's less appropriate.

Both of these require us to work together. As sustainability professionals we need to be upfront and honest about what worked in our projects, and what didn't. This might sound a bit grand - but we owe it to future generations of sustainability professionals.

Continual failure in mega projects benefits no-one.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.