If they can charge them, they will buy them: e-buses and e-trucks

Electrifying heavy transport, such as buses, vans, and trucks, is going to be a key part of the decarbonisation of transport, and a major contributor to reducing urban air pollution.

Summary: Switching to electric vehicles is not just about passenger cars. Buses and trucks are really important as well. Most people think about trucks as being those massive 40t vehicles that speed up and down our interstates/motorways, but trucks is about way more than that. And most buses and delivery vehicles (a better word than trucks maybe) go back to depot at night or site at a logistics warehouse for extended period - making their charging a lot simpler than you think.

Why this is important: If you live in a city, and to be fair most of us do, you probably think that transport is mostly about cars, plus buses, taxis, and if you live in Asia, LatAm or Africa, motorbikes/scooters. But if you head out into the suburbs or travel on our main roads, you realise that trucks are just as important.

The big theme: Transportation has the highest reliance on fossil fuels of any sector. Approximately 95% of its energy comes from them. For 45% of countries transport is the largest source of energy related emissions and it is the second largest source for the rest. Changing how we transport ourselves and our goods helps with both climate change and with health and well-being issues and is a rich vein for investment.

The details

Growing up in New Zealand in the 1960’s and 70’s people had a phrase to describe a massive opportunity … “imagine if you could sell a bicycle to every person in China”. How the world has changed. But even then the phrase had lots of weaknesses - sometimes the obvious big opportunity is not the most practical one. Taking just one point, think about the practicalities of reaching every individual in a country as big as China.

There are some parallels with EV charging. Most people think about this in relation to passenger cars. After all, there probably will be hundreds of millions of them globally on the road in a few decades. But, there is another opportunity, less obvious maybe, but still really interesting and potentially easier to access.

Electrifying heavy transport, such as buses, vans, and trucks, is going to be a key part of the decarbonisation of transport, and a major contributor to reducing urban air pollution. While the demand for electric buses is already strong, electric vans and trucks are only just starting to really take off. Which makes now a good time to build out the required charging infrastructure. And this might look very different from what you first think.

If we just look at Europe (we will cover other regions in later blogs), the ACEA estimates this could be a €94bn (by 2030) investment opportunity, of which €50bn is for light commercial vehicles (vans) and €45bn is for trucks and buses. This includes hardware costs, labour, the necessary electricity grid upgrade work, and the cost of building the required renewable electricity production supply.

Why this is important

Clearly, as passenger EV demand (both car and scooter) accelerates, providing charging infrastructure and hardware is going to be a big opportunity. Although the opportunity might turn out to be more about software and systems than hardware.

In thinking about EV charging, we should not overlook the demand for charging trucks and buses. In fact, it arguably might become a more interesting commercial proposition. If you ask most investors to visualise truck and bus charging infrastructure, many, if not most, will picture high speed chargers at road side service areas, dotted along our main road network. But that image is wrong, or more strictly not the total picture.

Recent research (which we will explore later in the blog) suggests that the largest proportion of charging will actually take place in depots, and at warehouses and other logistics facilities. Yes, long distance trucks will need roadside high speed charging, as will other Heavy Goods Vehicles (HGV’s) and Vans, when they do the occasional longer run. But for most trips trucks and buses can either charge when they return to the depot, or as they are being unloaded/loaded at a logistics facility.

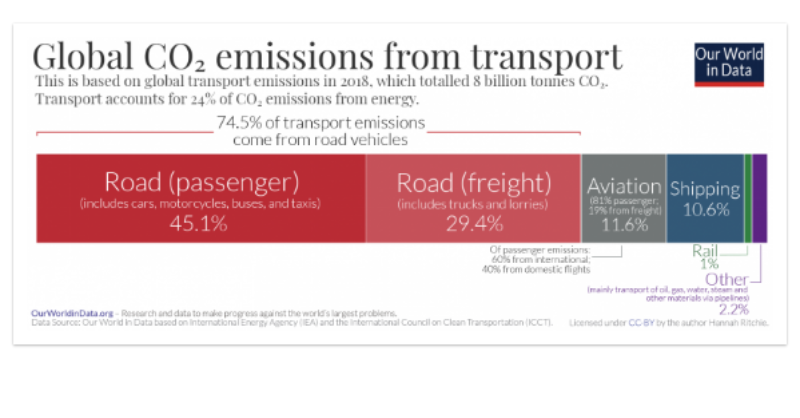

We know that transport is a big GHG emitter. According to the IEA, the total transport sector emits c.7.5 to 8Gt of CO2e pa, so between 21% and 24% of our global energy related emissions, depending on how you measure it. It's a big deal, something that we all know. Part of the reason for why it's important is that nearly all of the input energy currently comes from fossil fuels (mostly oil). Digging down a bit, according to Our World in Data, roughly 45% of transport emissions come from road passenger transport, nearly 30% from road freight and then roughly 12% from aviation and 10% from shipping.

In Europe, which is the focus of this blog, trucks, city buses, and long-distance buses are responsible for some 6% of total EU greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and more than 25% of GHG emissions from road transport.

The good news is that the electric bus market in Europe grew 26% last year, with 4,152 units registered. In 2022 around 30% of all registered city buses were zero emission. The not so good news is that only 0.5% of new trucks sold in the EU are electrically chargeable (battery electric, plug-in hybrid), and they only represent 0.2% of all trucks on the road today.

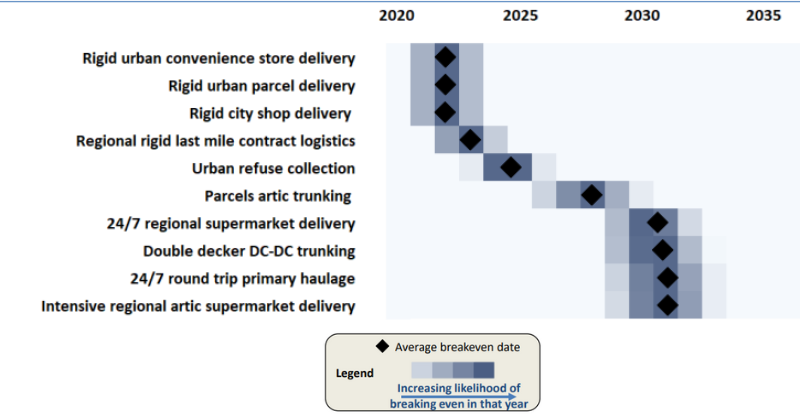

This however is expected to start to change soon, at least in some truck and HGV size ranges. Research carried out by Element Energy (2022) suggests that for many applications cost breakeven could happen over the next decade (sooner for some applications).

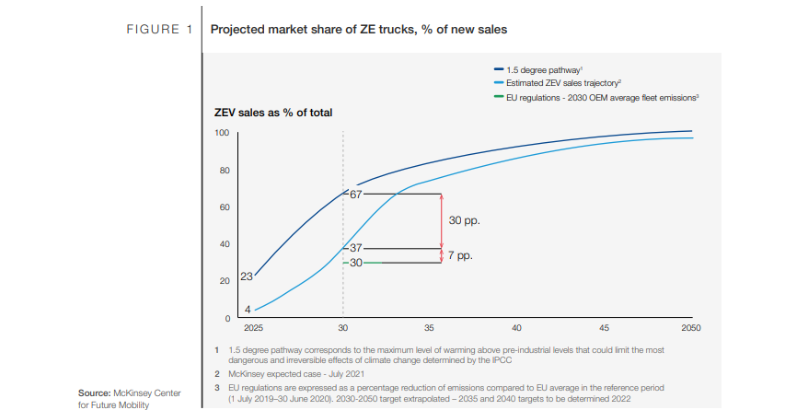

A 2021 forecast from McKinsey suggests that by 2030, 37% of new medium and heavy duty truck sales could be zero-emission in Europe, corresponding to around 150,000 vehicles. So, now is a good time to start thinking about the HGV and Bus charging market, from both a sustainability and financial investment perspective.

How trucks and buses get used

There is not one simple use case for charging HGV’s, vans and buses. It is important to first understand how they get used, and then translate this into the best way to charge them.

Starting at the higher level, logistics and public transport is, in financial terms, a low operating margin and high tangible capital business. Which is an investing way of saying, both industries use lots of fixed assets such as buses, trucks and vans, and they work in a very competitive environment, where profit margins are generally low. This makes them somewhat reluctant to try dramatically new ways of working, after all they could turn out not to work and the margin of safety between success and failure is slim. So gradual change is best.

The good news is therefore that transport electrification actually doesn’t change the operating model very much, similar trucks doing similar things, just with a lower cost of operation. And while the upfront cost might be higher, the whole life cost is expected to be lower, and its the whole life cost that matters to bus, truck and logistics companies. This is very encouraging in terms of driving change.

So how much change, and how quickly?

In March last year, the European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA), prepared what their European EV Charging Infrastructure Masterplan. They built this by carrying out interviews with dozens of industry bodies and experts., trying to create a detailed picture of the actual changing needs of the industry as it electrified. While some analysts latched onto the investment needed (up to €280 bn between now and 2030), or the requirement for roadside high speed chargers (all highlighted in the executive summary), we think the really interesting detail was actually deep in the report.

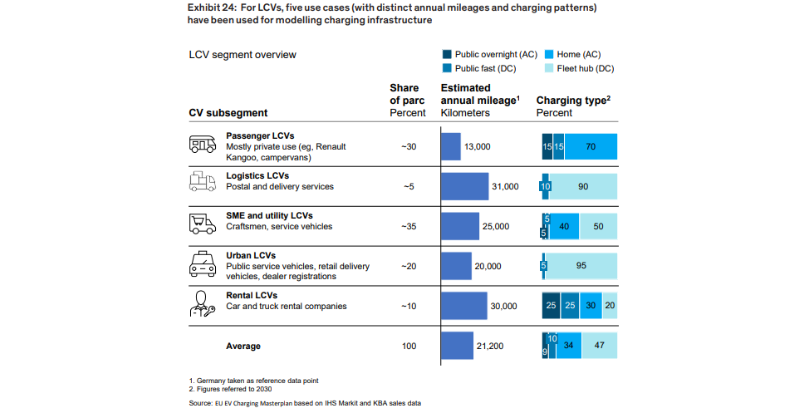

They analysed the driving behaviour of the different types of heavy commercial vehicles (including the distance travelled per day) and then created a framework for where they could charge, what types of chargers they would need, what the electricity demand would be, and what this might all cost.

Thinking about distance travelled.

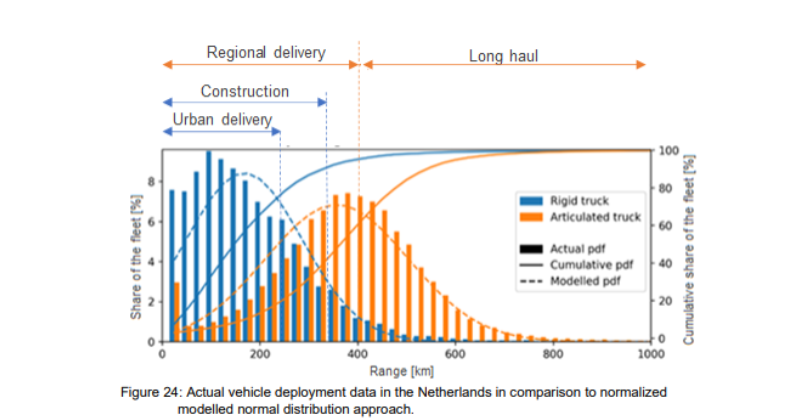

We have already highlighted in an earlier blog (add blog source) that most commercial vehicle use actually involves relatively short distances of travel. According to Eurostat, c. 40% of all European freight tkm (weight multiplied by distance travelled) involve journeys of less than 300km. But this only tells part of the story. Different vehicle use cases actually involve very different distances travelled. This is illustrated using data from The Netherlands, where urban delivery and construction related traffic travel much shorter distances than similar trucks used for say regional deliveries.

And, we have to be aware that “average” distances travelled (as per the Eurostat data) can hide the fact that some vehicles will travel more than this on some days.

This can mean that for a truck to handle an average of say 400km per day, it might drive 535km or more on 10% of days - Techno-economic uptake potential of zero emission trucks in Europe 2022

Where can they be charged if they go electric?

Putting all of this analysis together, the ACEA report estimated the annual km travelled, and the charging requirement, for five different types of commercial vehicles.

A couple of points leap out from this chart.

The first is that between 90% and 100% of journeys for urban and regional trucks, plus municipal and regional buses, can be covered using charging at a fleet hub. This group covers something close to 60% of commercial vehicles (by number). It's really only long haul trucks that need material public fast charging. So, something close to 60% of commercial vehicles will largely need only a limited “on the go” charging solution.

The second point is the requirements of long haul trucks. These are the vehicles that the Eurostat data has consistently covering more than 300 tkm per journey. Basically their charging needs are a lot more complex.

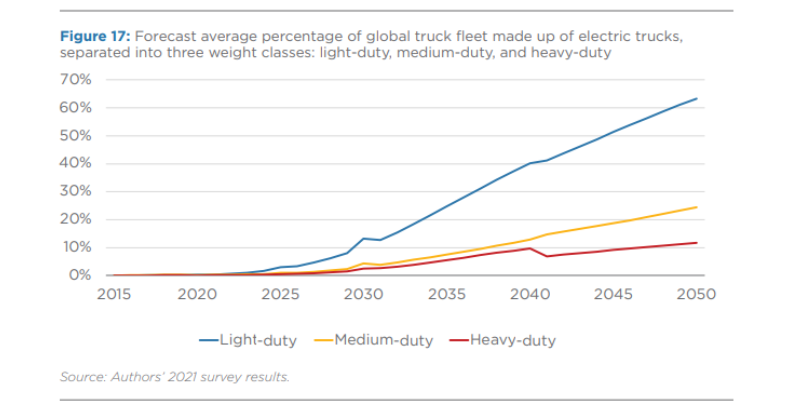

Recent research from the Centre on Global Energy Policy at Colombia suggests that not only will the EV segment for heavy trucks be the slowest to get traction, but that even by 2050, heavy duty EV trucks could still be only 10-15% of the total global heavy duty fleet.

However, the penetration rate is likely to vary massively by country. Regions such as the US, where distances travelled are large, are likely to see lower market share. By contrast, densely populated countries such as the UK, could see c. 65-75% of their rigid heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) and 30-35% of their articulated HGV’s being able to operate sustainably and productively without significant reliance on future charging infrastructure anywhere other than their home depot.

To be clear, there is a lot of debate about this. Some analysts point out that as battery technology advances, and as we roll out roadside fast charging networks, many of the apparent barriers to electrification of long distance trucks actually disappear, or at least become more manageable.

And, in some countries we may see the emergence of ERS/Catenary systems

What might charger demand look like?

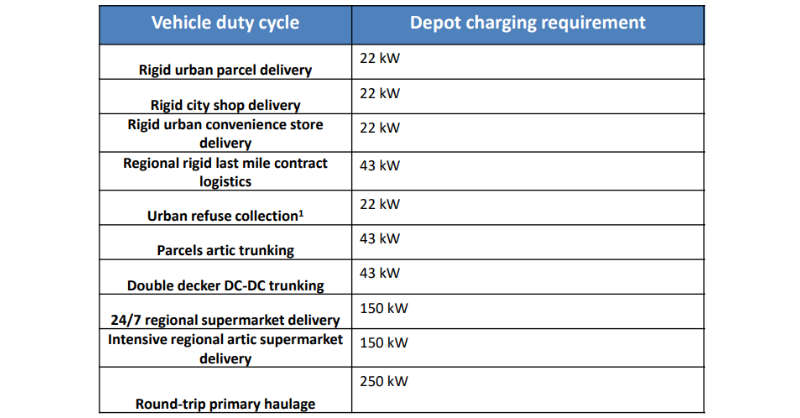

So what does a bus/HGV charger system look like and how does it compare with passenger EV chargers?

A typical at home or business park EV slow or “trickle” charger normally has a charging capacity of between 3.5kW and 22kW. At the higher end, 3 phase power is generally required, but in most cases installation into the existing home or building AC set up is straightforward. This would typically be used for overnight charging or slow charging while the driver is at work. To give this context, a small fan heater is around 2kW.

Bus chargers tend to be higher power DC, ranging from 60 kW to 120 kW onboard for opportunity charging on the route, through to 150 kW to 600 kW for charging in a depot. Buses can also use overnight ie slow/lower power chargers, these are typically 30 kW to 150 kW.

Truck chargers are broadly similar. The table below from a November 2022 report from Transport & Environment, sets out the charging requirements for a variety of truck types. These range from 22kW (similar to the top end of at home charging) for applications such as at depot charging of parcel delivery vehicles, through to 250kW plus for round trip primary haulage (at depot and at warehouse destination - for charging while loading and unloading).

The new roadside truck charging networks have larger charging systems (as they aim for quick charge times). For instance, the recently opened network of roadside chargers in Germany are 300kW . These can each recharge more than 20 e-trucks per charger per day, delivering enough power in 45 minutes to cover 200km.

To give a point of reference, the high end EV passenger car chargers such as the Tesla Supercharger, the IONITY rapid-charging network and Gridserve’s Electric Highway network all feature units capable of 350kW charging speeds.

💡

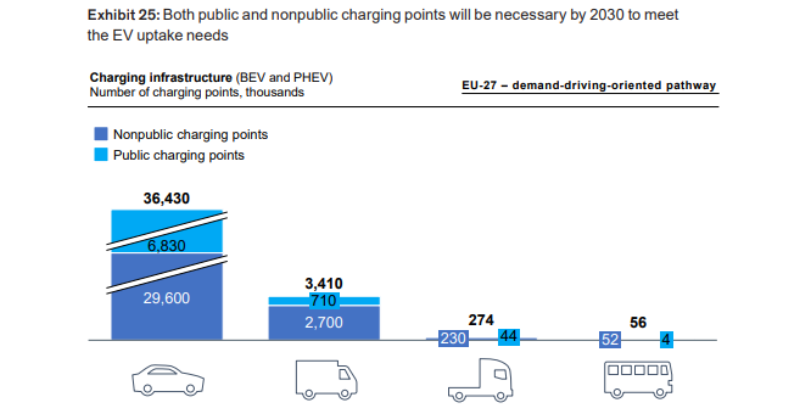

The ACEA report highlighted above estimates that in total, by 2030, the European truck and van fleet will need 3.4m chargers for vans (2.7m in depots), 274,000 for trucks (230,000 or 84% in depots) and 56,000 chargers for buses (52,000 or 93% in depots)

What might this all cost?

The ACEA report referenced above estimates that the total cost of building out the required van, truck and bus charging network, just for Europe, will be €94bn (by 2030), of which E50bn is for light commercial vehicles (vans) and €45bn is for trucks and buses. This includes hardware costs, labour, the necessary electricity grid upgrade work, and the cost of building the required renewable electricity production supply.

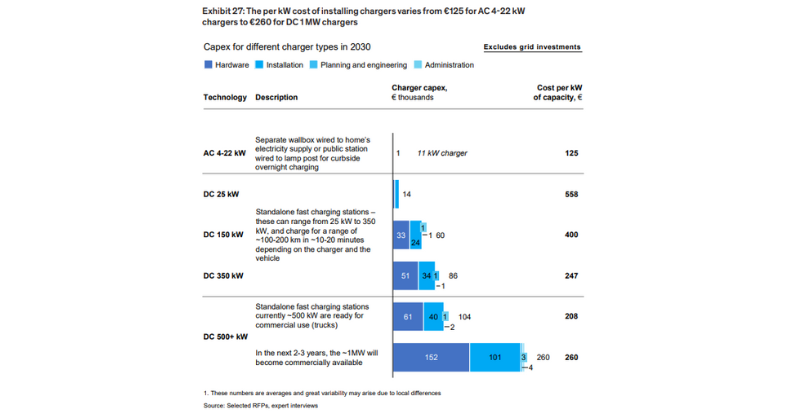

The big cost element is for fast DC chargers, for passenger vehicles, vans, trucks and buses. These are much more expensive to build than the at home trickle chargers. Total DC based capex (including for passenger cars) is expected to top €120bn by 2030. They cost between €200 and €558 per kW of capacity, compared with the smaller AC units at c. €125 per kW. Note that 1MW systems, so twice the size of the larger 500kW fast charging systems already available for trucks etc , are expected to be available in only 2-3 years.

Conclusion

In Europe, we can reasonably anticipate that the use of electric trucks and buses, for everything other than long distances, will become the new normal by the end of this decade. While many analysts focus on selling trucks (and buses), to us the really interesting opportunity is charging. This not only offers the potential to earn a fair financial return, but it positively contributes to decarbonising one of the regions big GHG emitters.

These changes are largely driven by improving economics. And while the industry may need public financial support for public fast chargers, the logic behind in depot charging makes the financial case much easier to make. In the period out to 2030, this could be a €94bn investment opportunity.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.