Human rights doesn't respect country boundaries

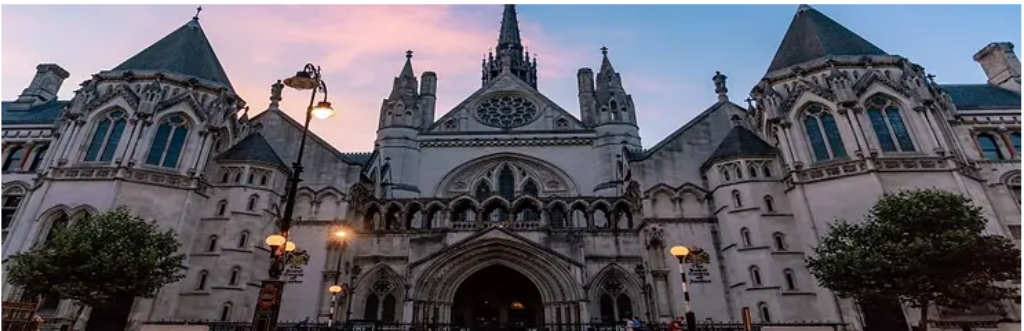

In late July London’s Court of Appeal agreed to reopen a $7 billion lawsuit by 200,000 claimants against Anglo-Australian mining giant BHP

Summary: In late July London’s Court of Appeal agreed to reopen a $7 billion lawsuit by 200,000 claimants against Anglo-Australian mining giant BHP – a case regarding the dam rupture behind Brazil’s worst environmental disaster in 2015. This decision has opened the way for parent companies to be held accountable for the acts of their subsidiaries as well as for acts they commit on foreign soil.

Why this is important: Companies and investors used to think that legal action could only take place in the country where the breach occurs, that the parent company was either immune, or that they could stall compliance for a long time. But is this assumption going to be correct in the future?

The big theme: Human rights issues are moving up the political and social agenda. And this goes a lot wider than most companies and investors will expect, covering supply chains, and the right to be protected from harm, and for culture and ways of life to be respected. And these rights increasingly have legal and financial teeth.

The details

Summary of a study published in The Guardian:

In late July London’s Court of Appeal agreed to reopen a $7 billion lawsuit by 200,000 claimants against Anglo-Australian mining giant BHP – a case regarding the dam rupture behind Brazil’s worst environmental disaster in 2015. The collapse of the Fundao dam, owned by Samarco – a venture between BHP and Brazilian iron mining firm Vale, killed 19 and destroyed a number of villages – which means houses, livelihoods, and futures for inhabitants, as a more than 40 million cubic metres of mining waste swept into the Doce river and subsequently reached the Atlantic Ocean over 600 km away. The case will probably be heard in 2022 and in all likelihood be appealed subsequently to the UK Supreme Court.

Why this is important

In terms of context, in 2019 the UK Supreme Court allowed Zambian villagers to sue miner Vedanta in England for alleged pollution in Africa and in February 2021 it permitted Nigerian farmers and fishermen to pursue Royal Dutch Shell over oil spills in the Niger Delta. In this case Nigerians from the Ogale and Bille communities alleged they had suffered decades of pollution, including the contamination of their water wells with potentially cancer-causing chemicals, as well as the devastation of mangrove vegetation, all of which was documented by the UN in a report in 2011 (following a case against RDS in a New York Court from 2009).

The high court ruled in January 2017 that Shell was not responsible for the harm because it was merely a holding company that did not exercise any control over SPDC, which was the company operating in Nigeria. But the Supreme Court held that the appeal of the claimants – who argued that they could not expect justice in a Nigerian court for this case – “had a real prospect of success” and should be heard in London. The Supreme Court determined that there is a good arguable case that Shell is legally responsible for the systemic pollution affecting the Ogale and Bille communities, overturning the lower Appeals Court’s decision by stating that it had “materially erred in law” when it ruled against the claimants

This decision has opened the way for parent companies to be held accountable for the acts of their subsidiaries as well as for acts they commit on foreign soil when the justice system in the affected country is deemed to be too lengthy or not effective. Their responsibility stems from the significant control they exercise over the subsidiary and its operations, towards which they are thus obliged to exercise duty of care. The rulings represent a turning point and could also affect other common law countries such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, where it could constitute a precedent to grant access to an effective remedy to the impoverished communities whose rights have been violated by multinational corporations.

The environmental impact of operations and investment is a source of new laws, standards, and case law. Some are very technical and specific regarding e.g. emission data, spillage, waste management. But when harm is done to a community of individuals the link between human rights, duties of care, and environmental damage becomes not only clear, but a basis for lawsuits. Specifically, the recognition of a duty of care to protect against the harms associated with environmental impact has given prospective litigants additional choice of grounds and has emboldened the use of existing human rights standards laws.

The upcoming EU regulation on Human Rights Due Diligence (HHDD) will be a further step in this direction, requiring not only EU based companies, but all EU operating companies to identify, prevent, and mitigate – e.g. through the establishment of an oil spill response plan – adverse human rights and environmental impacts on their entire upstream and downstream value chain. Plus, they must account for how adverse impacts are addressed, even if such impacts do not take place within EU borders. On the definition of the scope of the HHDD obligations, the UNGPs in Principle 13 state clearly that companies should (also) seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts “that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts.” This means that extra-territorial obligations will become ever more important (a subject we will be coming back to in future blogs).

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.