How should we engage with Oil and Gas companies?

Engagement is now a big part of sustainability investing, but I argue that it's still in its infancy. It's not an “invest in renewables vs invest in O&G debate”, it's more about who is best placed to invest this capital wisely, the upstream O&G company or their shareholders.

Summary: Part of the engagement process should involve us thinking like corporate raiders - not in terms of the outcomes they seek, but the process they use. It's not an 'invest in renewables vs invest in Oil and Gas (O&G)' debate, it's more about who is best placed to invest this capital wisely: the upstream O&G company or their shareholders. Any engagement has to start from a position of looking to create financial value over the long term.

Why this is important: Climate-related activist engagement is likely to increase. Non-profit organisation ClientEarth alleging that Shell's directors breached their legal duties by failing to manage climate risk or plan for the energy transition is one such example.

The big theme: The O&G sector is likely to play an important part in the sustainability transitions. The finance sector needs to support the sustainability transitions. We need to understand the real world complexity and how to effect change. Otherwise we end up investing our capital in projects that make little or no difference, other than to make us feel good - what economists would call a misallocation of capital on a grand scale.

The details

Corporate change can be brought about through the 'three P's' - Persuasion, Pressure and Profit. Persuasion, because you are trying to get the board and management to see the problem differently, and as a result to select a different strategy. Pressure, because there is always an implied threat in any engagement. Possibly the best pressure is to destroy their end markets, by supporting Electrification (EV's, heat pumps, industry decarbonisation etc). And price (share price), because your engagement, if it's going to be successful, must have an element of producing a better financial outcome.

Engagement is now a big part of sustainability investing, but I argue that it's still in its infancy. The thing about engagement is that it really should have a very concrete objective - "through my engagement with this company I want them to do XX". And XX is going to produce a different outcome than their current strategy.

When I worked in asset management, one of the roles that was poorly understood was that of a product specialist. For those from outside the industry, this person sat between the fund management team, the sales people and the client. It's a really important role, for which you need an unusual combination of skills.

I was lucky to work with one of the best (yes, that's you Steve). One of the many things he taught me was that it doesn't matter what you want to communicate, what matters is what the client needs to hear. I don't mean you lie to them. What I mean is that everything about your message (narrative) has to crafted with them in mind.

"facts and logic are not the best tools for altering peoples opinions"

Tali Sharot (The Influential Mind)

Which rather neatly brings us back to engagement. Engagement is about getting a company to stop doing something, and to start doing something else instead. This means engagement is a lot harder than many people think. It's an odd mixture of persuasion, pressure and profit.

Persuasion, because you are trying to get the board and management to see the problem differently, and as a result to select a different strategy. Pressure, because there is always an implied threat in any engagement. And price (share price), because your engagement, if it's going to be successful, must have an element of producing a better financial outcome.

Good strategy vs Bad strategy

As Richard Rumelt says in his excellent book (Good Strategy/Bad Strategy), in developing the company's strategy "leaders must diagnose the critical obstacles to forward progress, and then develop a coherent approach to overcoming them. This may exploit insights into the implications of changes in the company's external environment".

This description particularly applies to Oil and Gas companies. They face a material long term challenge - the demand for their product will almost certainly decline. And the world around them is changing. Legal and social pressures to reduce CO2 emissions will increase, and better alternatives to their products are becoming more available.

So, the question for investors is then what change do you want them to make, and how do you best engage with them to make that change happen?

Thinking about O&G engagement differently

How ESG/Sustainability relates to the Oil and Gas (O&G) industry has been frequently in the news over the last few years. There are two distinct ESG related schools of thought. The first is divestment. The second is engagement. The first one is easy, if you are not invested, your ability to influence change should be focused in the political arena. If you are invested, and see engagement as the solution - how should this happen?

Some really important caveats

It's highly unlikely that any publicly listed upstream O&G company can be persuaded to do something that clearly destroys financial value. Leaving aside arguments about fiduciary duty, if they announce a value destroying plan, their share price will likely fall, and another company can then come in and buy them at a discount, reverse the old plan and make a profit. That's just how our financial system works.

So, any engagement has to start from a position of looking to create financial value over the long term. This however, doesn't mean a "business as usual" scenario. Financial value is a forward looking concept, and if the external environment in which the company operates changes, then the company needs a different plan. The sustainability transitions are going to create massive change, change that very few companies will be immune to. So, all companies need a new strategy or plan. For some, such as in upstream O&G, the new plan could be very different from the current plan. The question then is which plan.

Additionally, the rundown plan for an upstream O&G company might, if executed successfully, mean that the company's profits actually increase in the short term and hence their share price might actually rise. Part of the reason for this is that many analysts have suggested that over the last decade, the O&G industry has not spent enough to maintain current levels of production. According to analysis by Deloitte current annual capex is approximately US$375 billion, and minimum annual capex required to offset field declines is estimated at US$525 billion. If demand exceeds supply, the oil and/or gas price will rise, and the O&G upstream profits will likely follow.

Of course, if our analysis is correct and fossil fuels are gradually phased out (demand replacement) as we move toward Net Zero, then the upstream companies collectively become worth less, or in some scenarios worthless.

Setting the scene

Before exploring this some more, let's set the scene properly. First, just how important are the publicly listed O&G companies?

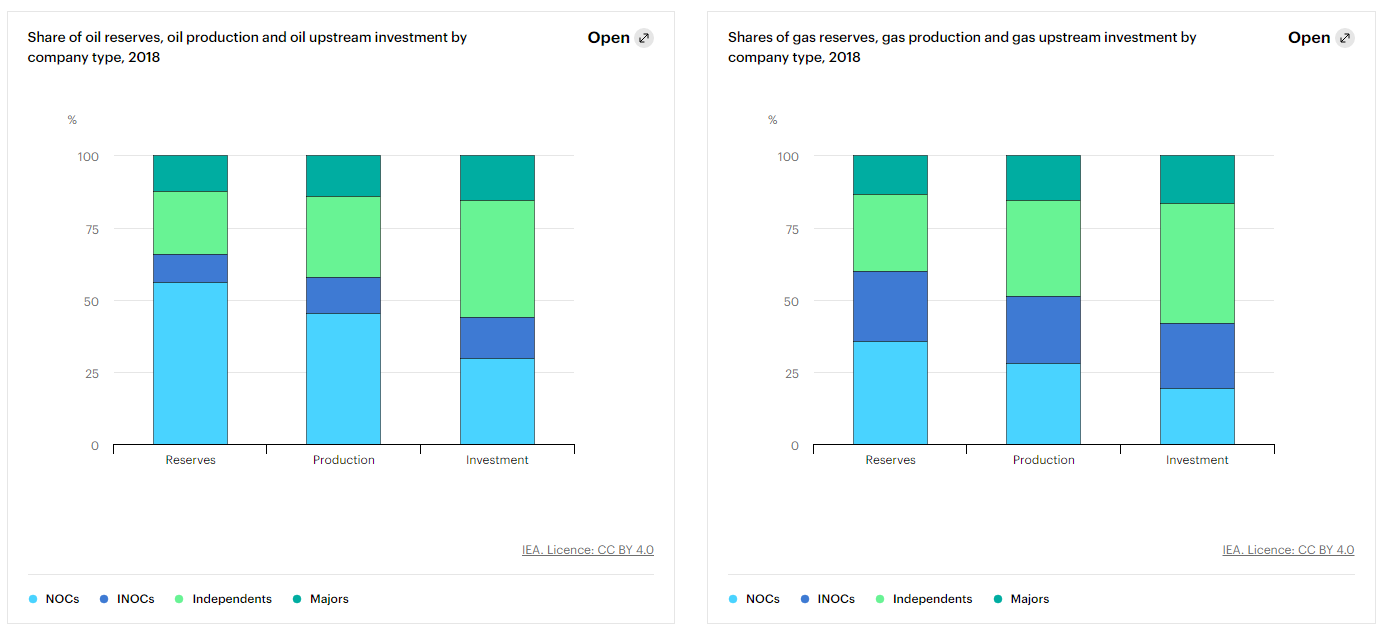

“attention often focuses on the Majors, seven large integrated oil and gas companies that have an outsized influence on industry practices and direction. But the industry is much larger: the Majors account for 12% of oil and gas reserves, 15% of production and 10% of estimated emissions from industry operations."

Further more...

"National oil companies (NOCs) – fully or majority-owned by national governments – account for well over half of global production and an even larger share of reserves. There are some high-performing NOCs, but many are poorly positioned to adapt to changes in global energy dynamics”.

So, from an engagement perspective, while getting the oil majors to change will be a positive step forward, it will have a smaller impact than many people seem to think.

Second, some simple economics - the supply and demand model. I think this gives us a useful financial framework to think about how best to drive change in the upstream O&G industry. This model sets out, in a simplistic way, how suppliers (in this case the upstream or producing O&G companies) change their output in response to higher or lower costs AND higher or lower levels of demand. If you want to understand the model better, this is a useful introduction from the MIT OpenCourseWare programme (you might want to skip forward to around 10 minutes in).

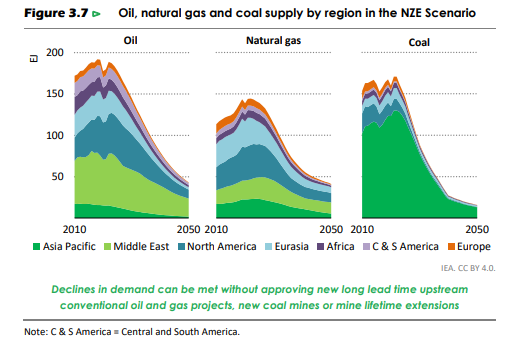

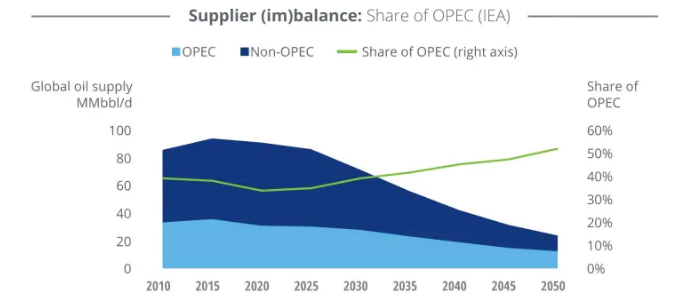

The chart below shows the second scenario, as we electrify, demand for O&G falls, and both prices and output also fall.

The next question then is how do we want the upstream O&G companies to respond to these likely changes? If we are successful, as a society, in increasing their costs and reducing demand for their product, all other things being equal, they will become less profitable. It might take time, perhaps decades, but gradually those upstream O&G who have the weakest competitive advantage, high production costs or poor distribution, will become less and less attractive as investments. Eventually, we reach a stage where only the lowest cost producers, such as Saudi Arabia, will be profitable (let’s park the question of will this make the O&G markets more susceptible to cartels and increasing price instability).

So, either we want O&G companies to start to transition to renewables (the most popular scenario among many sustainability professionals) or we want them to go into run down, gradually cut capex, focus on their lowest cost of production assets and begin to return more and more cash to their shareholders.

Of course, this process of distributing surplus cash allows the shareholders to reallocate this cash to renewable investments.

Can thinking like a corporate raider help sustainable investors?

So, having set the scene, this is a blog that we recently wrote for the The European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI) … we aim to stimulate debate.

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!”

Upton Sinclair 1934

Successfully engaging with Oil & Gas (O&G) companies depends much more on their individual characteristics than on what industry they sit in. I spent many years working at a large activist fund, and my argument is simple. The transition for the O&G sector is going to be really hard. To give it the best chance of success we need to think like an activist investor or a corporate raider.

When you say 'corporate raider' to people, they tend to picture Gordon Gekko from the movie Wall Street, or real world raiders such as T Boone Pickens. It's generally a derogatory term. So it might seem odd to argue that ESG investors can learn from how corporate raiders and activist investors work.

We need to use the language of finance

The bottom line is that we need to think about the transition company by company, rather than at an industry level. And use the language of finance wherever possible – it’s the language companies understand. This approach isn’t going to be cheap and it’s not going to be easy - but it's likely to work. Look at Engine One. It’s not about right or wrong, it’s what makes the best long term sense for the company and all of its stakeholders.

Our absolute number one rule -identify exactly what it was we want the company to do. And I mean exactly. Many debates start with peak oil, the risk of stranded assets, and the need to transition. This is a start, but we need to quickly move on to the company's individual circumstances. The first is probably how does their business model work, and what assets do they have? Are they lowest cost and easy to extract, or are they closer to the end of life and expensive? This requires a field by field review.

Do they have the will or the skills?

Then we have willingness. If senior management is unwilling to engage on the renewables option, it's unlikely that proposals to pivot to renewables would get traction. Conserve our resources for other battles.

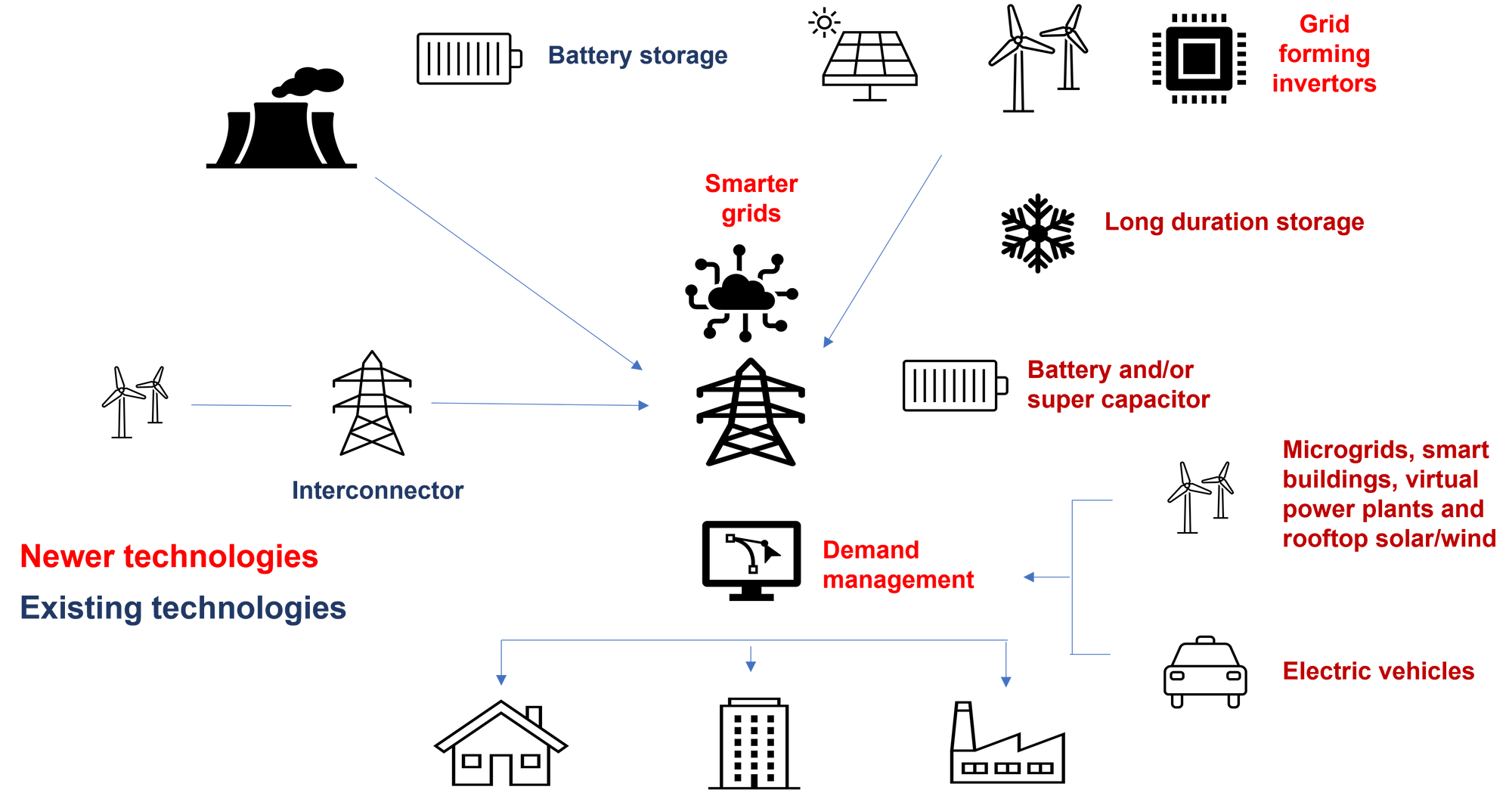

What about expertise, or in other words competitive advantage? Some skills may transfer (say drilling into geothermal), but most will not. Compare running an O&G field to running a solar farm. And activities such as electricity supply, storage, grid stability, interconnectors etc are even more different. Many companies will be unable to build the resources required to successfully execute a pivot. For these companies, the best path is to run down.

So what concrete actions do we want from these companies? No new exploration is an obvious start, as is methane emission reductions. After that it gets tougher. Do we want them to be able to buy existing O&G fields? The answer to that could be 'yes', which may not sit comfortably with some stakeholders. But scale is important, and as the run-down gathers pace, we should support consolidation.

On the finance side, we should starve them of free cash to spend on new projects. So get them to distribute all of their free cash via dividends and share buybacks. This might get bad publicity. But it will make it harder for them to backtrack.

Of course some O&G companies will have the capability to pivot to renewables. They have the right culture, or they may just get the economic imperative. But take care. In lots of transitioning companies the power, and promotion prospects, can still lie within the old business. And we need a clear and very concrete plan. What technologies will be the focus? How will they build competitive advantage? How will they build a new culture? If they are just providing capital, the financial markets can do that much more efficiently.

So - what is the pitch?

You need to transition, as there is a real risk of stranded assets. Our analysis leads to the view that for you the best option is rundown/pivot. If it's run down, no new fields and increased dividends; If it's pivot, we need a detailed “how to” plan. For both we need concrete metrics, so capex plans, dividend commitments - things we can track.

And to be clear, as well as supporting these companies’ strategy, we will be doing all we can to destroy their end markets. We will support the uptake of Electric Vehicles, the electrification of building heating/cooling and the replacement of fossil fuels in heavy industry.

Given this, your selected decision is not just a nice to have, it's a commercial imperative. Doing nothing could be your Nokia “burning platform” moment.

Then we build our alliances. We sell our plan to everyone and anyone who can help - politicians, NGO’s, existing & potential shareholders, and debt providers. This last group can be particularly helpful. If they believe that the company's credit position will deteriorate, they will be less willing to lend.

Our final rule - never make it personal

Why? By publicly attacking someone, you make them defensive and they stop talking to you. And you help to persuade people in their organisation who might have become voices of reason and compromise, that they need to close ranks.

Conclusion

Reducing our reliance on fossil fuels is going to be tough. The simplified message of “no new oil and gas exploration” is a good start in terms of mobilising public opinion, but on its own it’s not enough.

While our strategy is driven by our values, our tactics should be driven by what works. And in many cases it's thinking and acting like a corporate raider. Use the tools of the financial system to create change.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.