How much for green chemicals?

We know we need to decarbonise the chemical industry - its going to be tough, but a pathway now exists to do it in a financially viable way.

Summary: Switching to electric vehicles is not just about passenger cars. Buses and trucks are really important as well. Most people think about trucks as being those massive 40t vehicles that speed up and down our interstates/motorways, but trucks is about way more than that. And most buses and delivery vehicles (a better word than trucks maybe) go back to depot at night or site at a logistics warehouse for extended period - making their charging a lot simpler than you think.

Why this is important: If you live in a city, and to be fair most of us do, you probably think that transport is mostly about cars, plus buses, taxis, and if you live in Asia, LatAm or Africa, motorbikes/scooters. But if you head out into the suburbs or travel on our main roads, you realise that trucks are just as important.

The big theme: Transportation has the highest reliance on fossil fuels of any sector. Approximately 95 percent of its energy comes from them. For 45 percent of countries transport is the largest source of energy related emissions and it is the second largest source for the rest. Changing how we transport ourselves and our goods helps with both climate change and with health and well-being issues and is a rich vein for investment.

The details

When I first started working as a young engineer, I didn't really appreciate how strong the desire is in people to seek simple answers. And the tougher the problem, the greater desire we have for simple solutions. In the district that I looked after we had a steep hill, where we seemed to be constantly repairing the road surface. It was something we had to do roughly every five years, which given that a typical road surface should last 20 years, was just way too frequently. That section of road not only cost us a lot of money, it also had a higher than normal number of accidents.

I wanted to take some time to study why this was happening, so that we could come up with a solution that actually fixed the problem. The pressure however was to find a quick solution, to fix it now. I was lucky, our City Engineer had got tired of spending money on repairs that didn't last, so he was happy to take some time to try out different solutions.

Without his support, we would have carried on trying simple but wrong solutions.

In the spirit of asking the difficult questions and posing challenges to how we think about the complexity of the upcoming transitions, today we are going to start tackling the chemicals sector. This covers the vast range of raw materials that go into our fertiliser and our plastics.

If you are not an engineer I want to say up front, this is largely a non technical discussion. For those who want, and need, to understand the (really important) technical detail of the possible solutions, this is something we will cover in a later long blog.

For now I just ask that you accept that solutions exist, they are currently technically challenging to implement, they will take time to get to the wider market, and they are expensive.

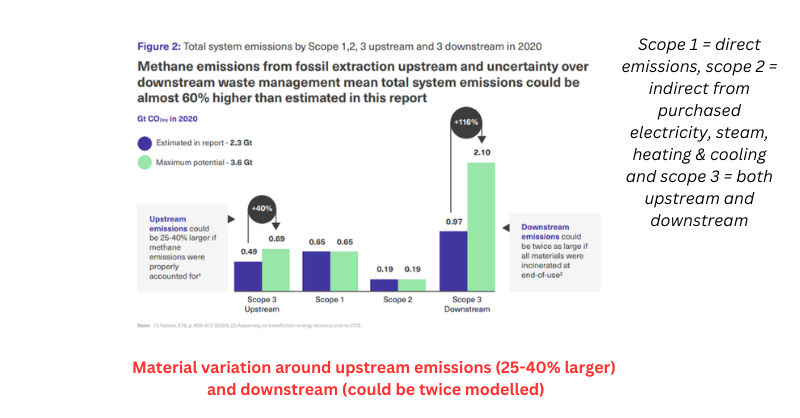

As a society, we understand the need to decarbonise the chemicals sector. It currently contributes (scope 1,2 & 3) more than 2 Gt CO2e pa, or somewhere close to 4% of our global GHG emissions. The range in the chart below reflects the uncertainty around how well we account for downstream and methane emissions.

And it is responsible for, directly and indirectly, material environmental and societal pollution.

Beyond CO2 impacts, the leakage of chemicals and downstream products (e.g. plastics and fertilisers) into the environment has a range of other adverse impacts on the nine essential planetary processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth system. The tolerable limits of human impact on these systems are referred to as “planetary boundaries”, and there has been increasing awareness that the chemical system is breaching many of these boundaries. Planet Positive Chemicals Systemiq 2022

But, unlike say Oil and Gas (O&G), the demand for these products is not going to reduce materially. And, we cannot just assume that better alternatives will be found, at least not quickly. As a result, transitioning the chemical sector is both important, and a major challenge - technologically and financially.

Technologically because there is uncertainty around the best pathway. We have some really good pointers as to the direction of travel, but we are still a decade or more away from having the full answer.

Financially because the new pathways will require very different means of production, exposing the industry to stranded assets.

As we pointed out earlier, the chemical industry is fundamentally different from industries such as O&G. Most citizens do not really care if the O&G industry survives financially (in the very long term). They know that at some time over the next three decades other alternatives will largely replace fossil fuels. O&G may survive in some form, but it will be a much smaller industry, a niche energy provider in a world of electrification.

By contrast, as a society we need a successful chemical industry. We just want it to work differently. Planet Positive Chemicals Systemiq 2022

Progress made in similar sectors, especially green steel, green ammonia, and to an extent renewables, shows us a possible pathway. That pathway has some technological uncertainties, but the one thing we know for sure is that it is going to need a lot of government support, both financially and politically. Plus it's going to need assistance from the end consumers - they need to demand, and be willing to pay for, greener products.

This is a massive challenge. It would be easy to write a hundred plus page report (as many others have done) and still leave many unanswered questions. From an investing perspective, it's easy to put it in the “too hard” pile, to assume business as usual, with only incremental changes.

I argue that this approach is short sighted. Change is coming, it doesn’t matter if it's going to be challenging, or that it's going to take time, it's coming. Our job as investors and decision makers is to anticipate the future. After all, a company's value is driven by its future, not its past cashflows. This is especially important in industries such as chemicals, where the assets have very long lives and where change takes time. So, it's important that we help the companies anticipate and prepare for the future.

Clearly, there is a balance. We cannot ask companies to go “too quickly”, if by doing so they risk their long term financial future. We discussed this in a recent blog on the O&G sector. If companies follow a plan that destroys financial value, they will be acquired by companies who care less. They will then reverse the plan and “create” free financial returns.

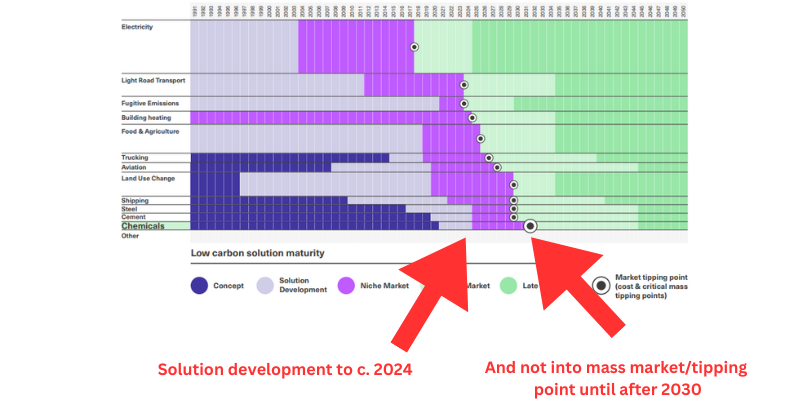

It is not in society's best interest that the greener chemicals companies fail. And we need to recognise that the transition will take time. The chemical industry is anticipated to be one of the last to tip towards a low-emissions model, with the initial development through niche markets taking place over the rest of this decade, heading out into the mass market from c. 2030 onward.

Why cannot this happen faster? Some of the answer is cost, but part of it is also how the industry works. Many years ago I worked in the gas industry. My time there taught me one important lesson. Chemical production processes are complex. Even when we know the different steps in the process, getting it to work as a whole, from end to end, takes time and perseverance. Lots of incremental changes, tested over and over again for their production, cost and safety implications. This is an industry that learns by doing. And it's an industry where the consequences of getting change wrong, from a safety perspective, can be very serious.

There is no time to lose. Long lifetimes for chemical industry facilities mean that investment decisions in the next few years will determine the trajectory of the industry during the critical decades out to 2050. “Wait and see” is no longer a viable strategy for corporations and investors in this industry. Planet Positive Chemicals Systemiq 2022

On the positive side, the companies that solve this challenge could be exceptionally well placed for the decades to come. The head start they get as first movers could allow them to generate superior profits by meeting the future demands of society.

You will recall my starting point - society needs the chemical sector to prosper.

The global chemical industry generates $4.7 trillion in revenues annually, representing ~4% of global GDP, and directly employs over 15 million people. The products from the chemical industry underpin our way of life, health and prosperity and our transition to a net zero emissions economy. They are present in the healthcare, packaging, agriculture, textiles, automotive, construction and many other systems, with 96% of manufactured goods depending on their use. Planet Positive Chemicals Systemiq 2022

This doesn't mean business as usual. The chemical industry will need to change and adapt, but in the main we are going to need many of the products they produce. We cannot just wish ourselves into a greener future.

One aspect that sometimes gets lost in the discussion is the upside. A recent report by Systemiq for the Center for Global Commons, estimated that “ the global transition to a circular and net-zero-emissions economy is an opportunity for the chemical system to grow annual production volumes 2.5 times by 2050”.

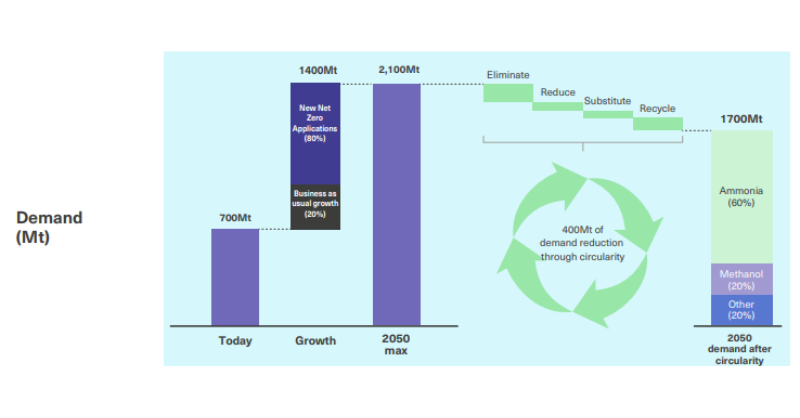

So, production could rise from 700Mt now, to potentially around 2,100 Mt by 2050, a CAGR growth rate of close to 4% pa. Of this extra 1,400Mt, c. 20% is from growth in existing applications and 80% is from “new” green applications.

But that is not the end of the demand analysis. Systemiq estimate that using circularity (also the topic of a future blog) 2050 demand could be reduced by c. 400Mt (around 20%) to 1,700Mt, still a market that is nearly 2.5x the current level of demand.

We have some questions with a few of these potential applications, specifically the use of ammonia in shipping and the energy sector, but broadly, the assumption of strong green driven growth for the chemical sector looks sound. So a positive financial background.

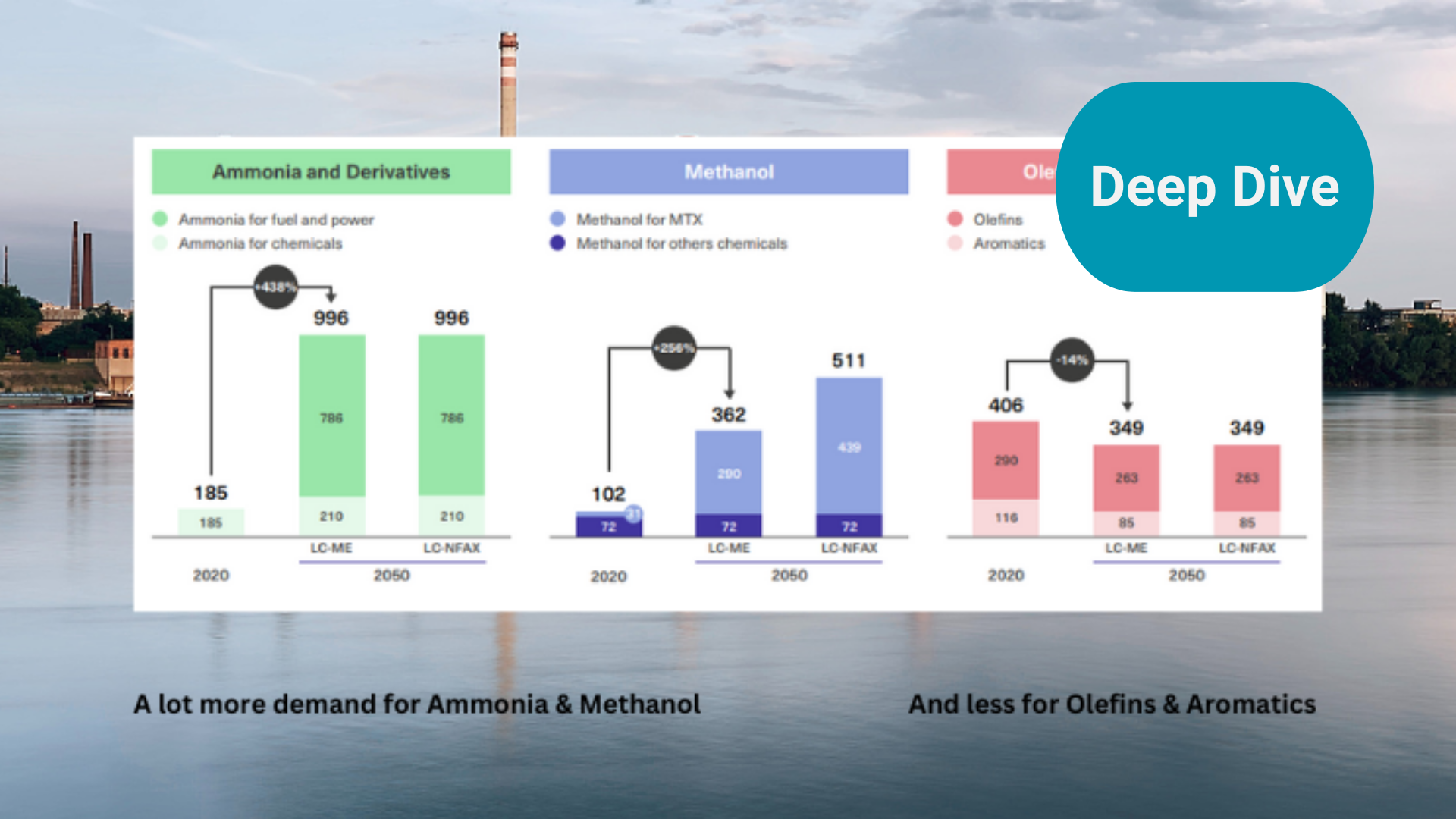

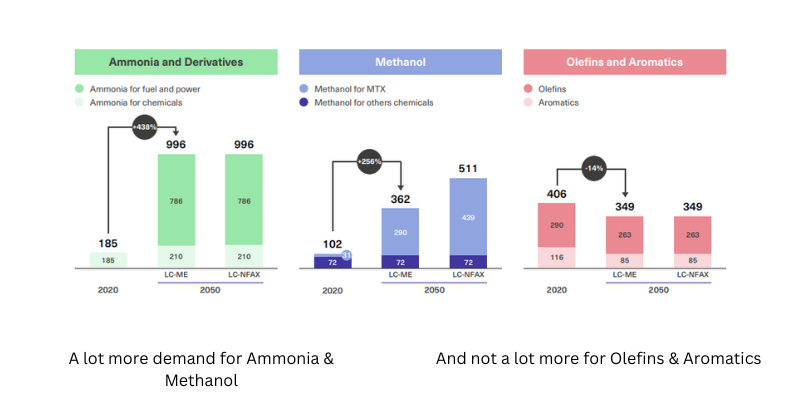

Interestingly, the winners of the future might look a bit different from what you might expect. So more Ammonia and Methanol, and less Olefins/Aromatics (mostly for plastics).

What might this all cost? This is where we hit the need for government (and end consumer) support. Again quoting from the Systemiq report ….

The chemical value chain will need to deploy an incremental $2.7-3.2 trillion capex by 2050 to achieve net zero, 51-70% of which is for ammonia. Planet Positive Chemicals Systemiq 2022

This works out (on average) at c. $90bn pa. How does this compare with current capex? It's roughly an increase of between 40-50%, so pretty material. Obviously, not all of this will come from the companies. If we want this spending to take place, the wider society will need to also contribute, through government grants, contracts for differences , carbon taxes, and premium pricing for green product. This is no different from the wind and solar sectors, green steel, and of course the massive financial assistance currently already provided to the O&G sector.

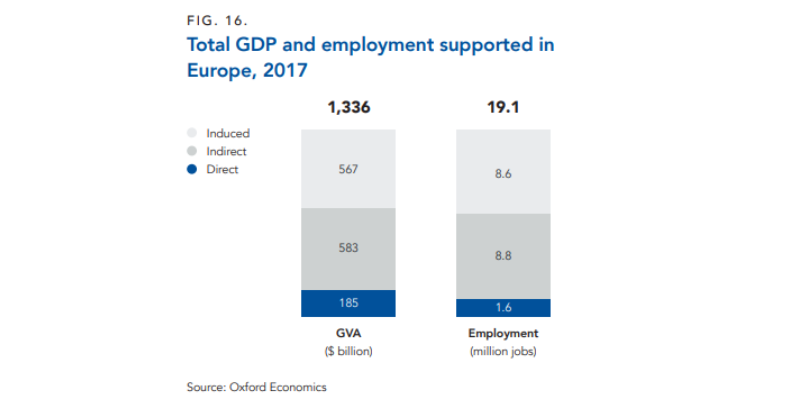

Looking specifically at Europe, why might governments and society want to fund this investment. I suggest as well as the obvious reason (it needs to happen if we are to hit our net zero targets) there are two more selfish reasons - jobs and energy security.

An Oxford Economics report stated that when supply-chain and wage-spending channels are included, we find that Europe’s chemical industry supported a $1.3 trillion contribution to GDP and 19.1 million jobs (2017). Only the Asia-Pacific region has a higher impact than this, at c. $2.6 trillion of total GDP contribution and 83m jobs supported. Even allowing for the fact that the report was prepared for The International Council of Chemical Associations (ICCA), its clear the Chemical Industry still a really important sector in terms of job creation and economic contribution.

And, given the current situation with energy costs, European governments must be increasingly concerned that these major centres of employment might move. Some current shifts might be to countries with lower operating costs and less regulation.

On this we note that BASF, the German chemicals giant, has recently approved a E10bn investment, in China. And during their recent results presentation, they specifically mentioned weaker European demand growth, structurally higher European energy prices and regulatory uncertainty. They went on to say that …

The significantly weaker earnings in Europe, especially in Germany, as well as the deteriorating framework conditions in the region make permanent cost reduction and structural adjustments necessary

Future shifts might be to countries that will have abundant and cheap renewable electricity. We discussed this in a recent blog on where green steel might relocate to, but its also going to also take on increasing importance for chemical companies. So in Europe maybe Spain and Portugal, but further afield into the Middle East and North Africa is also possible.

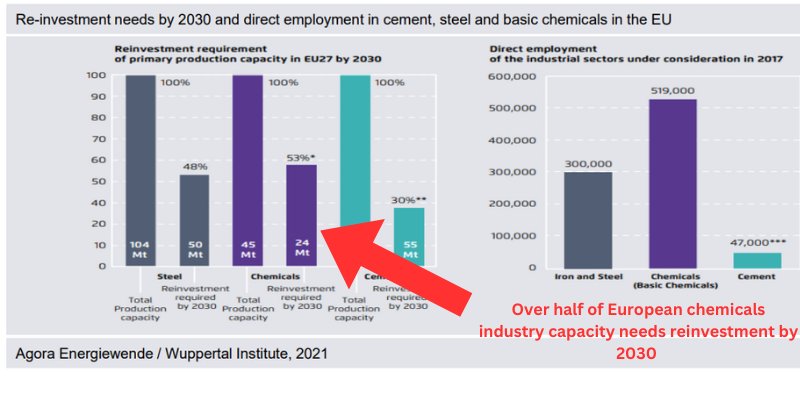

And Europe has another motivation. According to climate policy think tanks Agora Energiewende and the Wuppertal Institute, the regionsageing heavy industry plant and infrastructure (steel, chemicals and cement) is rapidly approaching the time when it needs material investment.

Conclusion

The time to act on chemical decarbonisation is rapidly approaching. There are many uncertainties, and it will take many years, but we can see a viable pathway. It's going to need a lot of government support, but the crisis being faced by the industry in regions such as Europe, should create a bias toward action.

As investors, we want the industry to begin to anticipate the upcoming changes. The technological uncertainties are material (the subject of our next blog on this topic) but given the progress that has been made in other green sectors such as renewables and steel, there is no reason to think that the challenges in the chemical sector cannot be overcome.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.