How hard is it to get rid of coal fired electricity?

It's not as impossible to get rid of coal fired electricity generation as you might think. And no - you don't have to replace it with gas. Low carbon electricity grids are within reach, but getting there takes time

Actually not as impossible as you might think. This is not to trivialise issues such as energy security. It's really important that countries are able to keep the lights on. This is not about turning off coal fired electricity generation tomorrow, it's about switching over time.

What prompted this train of thought was the recent Statistical Review of World Energy. This confirmed that coal retained its position as the dominant fuel for power generation, with fossil fuels (coal +gas) overall forming 60% of global electricity generation. And yet we know that coal is the highest emitting electricity generation source. The one we really have to cut first.

So can it be done? Well yes. As a finance person I tend to ask, who has done it already, and how did they do it? One country that has just about totally cut out coal fired electricity generation is the UK. And they did it without doing the thing that the sceptics say they would have to - they didn't add extra gas fired generation.

So, what can we learn from the decarbonisation of the UK electricity generation system ?

This is a What Caught Our Eye story - highlighting reports, research and commentary at the interface of finance and sustainability. Things we think you should be reading, and pointing out the less obvious implications. All from a finance perspective.

It's free to become a member ... just click on the link at the bottom of this blog or the subscribe button. Members get a summary of our weekly posts, including What Caught Our Eye and Sunday Brunch, delivered straight to your inbox. Never miss another blog post !

Statistic Review of World Energy

Lets start with the latest Energy Institute annual review. At the first read this has some good news, and some bad news. And the main bad news was that while the renewable share of total power generation rose from 29% to 30%, coal and gas remained the biggest source of electricity generation. By some margin, at a combined total of 60%.

This is not great from a GHG emissions perspective, especially given the amount of coal we burn. If we look at the Ember data, coal generates around 10,500 Terra-watt hours of electricity, and in the process emits around 9,500 megatonnes of CO2e. By contrast, the numbers for gas are around 63% of the generation of coal, for c. 41% of the emissions.

So getting rid of coal would be good, even if it's replaced by gas. But, it's even better if we replace it with low carbon sources. Which is what the UK seems to have done.

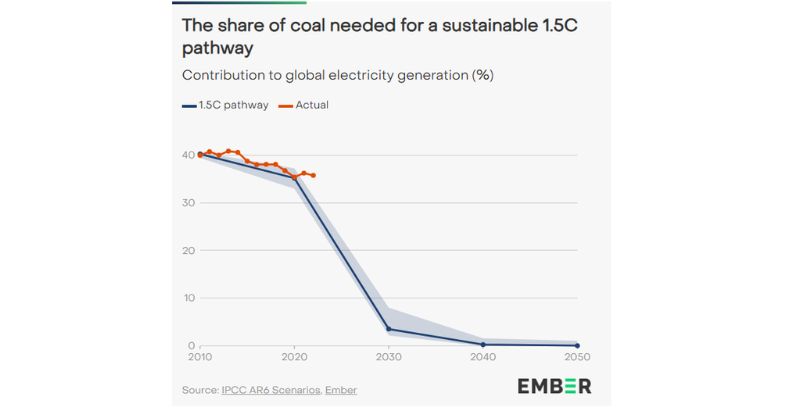

Just to give you some context, this is the chart that shows the pathway for the share of coal if the 1.5 degree target is to be reached. At a simplistic level, we could summarise this as so far so good, but the hard work starts now (or rather it needed to start last year). And the next decade looks a really big ask.

What happened in the UK ?

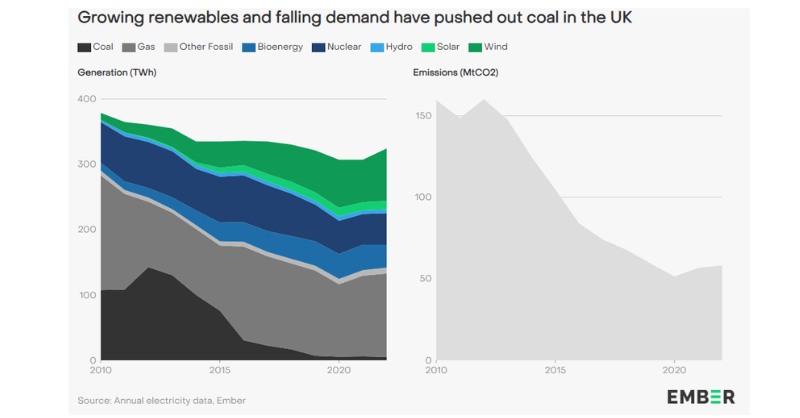

To quote Ember: "in 2010 the UK’s power supply was heavily dominated by fossil fuels, with coal alone generating almost a third of UK electricity. However, in just over a decade the UK’s power system has been transformed: coal now generates just over 2% of the UK’s electricity".

It's even more stark when you see it on a chart.... coal is the dark segment at the bottom of the left hand chart, with the bulk of the decline between c. 2011 and 2016. And it's been a gradual slide down since then, despite the disruption from the war in the Ukraine.

But the other trend that you should note is what happened to gas. Back in 2010 most analysts would have told you that you could not run an electricity grid with a high percentage of renewables. And what was considered high then was thought to be somewhere between 10% and 25%. And so many people thought if you closed down the coal generation, you would need more gas. And if not gas, then the other base load type generation - nuclear.

But instead, renewables took up the slack. Between 2010 and 2022 (this was a 2023 report), as a percentage of total generation, gas was down 15% and nuclear was down 10%.

How was this possible? Ember identified five key drivers.

The first was clear targets. The 2008 Climate Change Act set into law a whole-economy, legally binding target of an 80% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions below 1990 levels by 2050. This made it clear to decision makers that the use of unabated coal could not continue.

The second was actions that revealed the true cost of using coal - making it uneconomic. Some of this was from air pollution regulations (including the 2001 European Union Large Combustion Plant Directive). This came into effect in 2008. And then you had carbon pricing via the EU Emissions Trading Scheme. This started in 2005, but it really started to make a difference when the UK added the 'carbon price support', from c. 2013.

The third were policies to support wind. The UK is blessed with amazing wind potential, both in terms of how much there is and the shallowness of the coastline. Stable policy support led to enormous investment and rapidly collapsing prices for wind.

And fourth were changes to market incentives. These de-risked wind and made it investable at scale. The Capacity Market was part of this, but a material driver was the Contracts for Differences scheme. Under this the contracts fixed a ‘strike price’, which is guaranteed to be paid to the generators regardless of the market price. If the market price was higher, the generator pays back the difference, and in return if the market price is lower, they get the top up.

The final one was investment in the grid. There are a lot of moving parts to this, but the end result was that it was made easier, and quicker, to connect new renewables to the grid. We have written about this before, most recently in April 2024 on the lengthening grid connection queues in the US.

What can we learn from the UK experience?

The obvious one is everything, all at once. We need a series of actions, that together bring change. Relying on one lever and neglecting the others doesn't work.

The second is how long this can take. If we take c. 2008 as the start of the process, with the passing of the Climate Change Act and the European Union Large Combustion Plant Directive, then it took around a decade to make a real difference and c. 20 years for coal generation to get close to zero. And of course much of the ground work was done years before.

And the third is interconnectors. People tend to think about an electricity grid as ending at a country or regional boundaries. But why do we think this way. Sticking with a UK example, if it's ok to share wind electricity from Scotland, with consumer in London, why is it wrong the take surplus nuclear from France, or hydro from Norway.

This is why I described the latest Statistic Review of World Energy as being some good news and some bad news. Because yes, there is a lot of work to do, but we have pathways that have already worked.

I really encourage those who are working to retire coal, to read this report.

Please read: important legal stuff.