Health Equity - drugs and more

Health equity is a key sustainability theme that has solutions and drivers across all industries, not just pharmaceuticals. Why? Because disparities are not only a function of access to health care but also other factors including socioeconomics, the environment, race and gender.

Summary: Health equity is an important sustainability theme. We discuss what it actually is, why we care about health equity, the social determinants of health, Big Pharma's role, and health access including value-based pricing and innovations for remote locations.

Why this is important: Disparities are not only a function of access to health care but also other factors including socioeconomics, the environment, race and gender. Health equity considers starting points and is focuses more on outcomes of health rather than the inputs of the service provision.

The big theme: Health equity is a cross-cutting theme that has its solutions and drivers across all industries, not just pharmaceuticals. It is about providing the ability for people to attain the highest attainable standard of health regardless of their starting point. It is about equity and it is about social justice. To meet all of the sustainable development goals will require solutions that address environmental, social and economic problems. But the benefits will also be felt across all of those areas.

The details

In the 1980s in many towns and villages in a number of African countries including Mali, Sudan, Ethiopia and Uganda, it was assumed that by the time you were in your mid-teens you had itchy skin, started losing your sight and were likely blind by the age of 30. Of course life wasn't like that everywhere, but in those particular towns and villages they were blighted by a parasitic worm spread by the Simulium blackfly that breeds in rapidly flowing streams. The infection that the parasite caused is onchoceriasis or, as it is better known, 'river blindness'.

More than 99% of people infected with onchocerciasis live in 31 African countries although it is also present in Venezuela and in some parts of Brazil as well as Yemen. Historically it was controlled or at least attempted to be controlled by insecticides to kill the blackfly and stop it spreading the parasite.

The terrible bargain for sufferers was between blindness or hunger. The fertile lands near the fast flowing streams offered greater crop yields but also had greater numbers of blackfly.

In 1987, Merck established the 'Mectizan Donation Program' (MDP) giving away the drug which could treat onchocerciasis, and MDP in conjunction with local support programmes has resulted in the condition even being classified as eliminated in some countries (e.g. Colombia, Ecuador and Mexico) and declines in transmission and impact in a number of African countries.

There were costs involved in distributing the drug to, in some cases, remote towns and villages but there were economic benefits as a result including farmers being able to work more productively and children being able to attend and complete schooling.

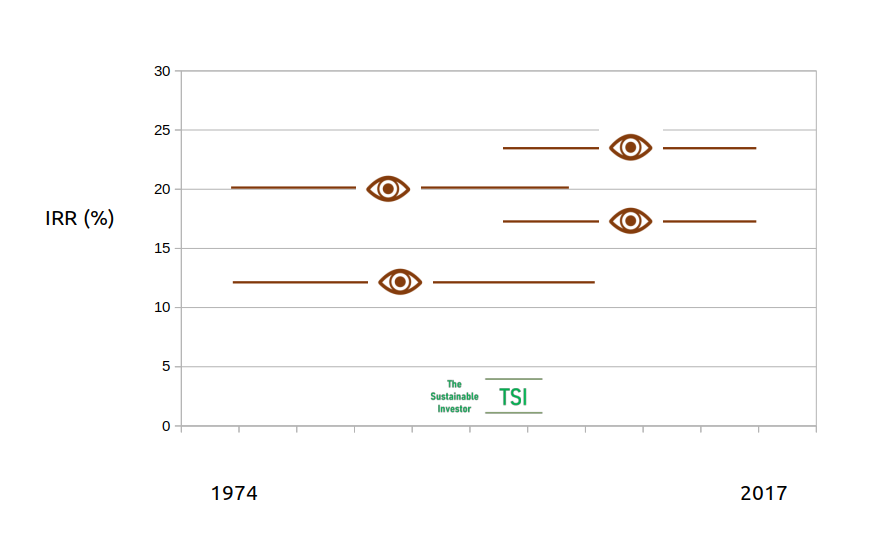

The chart below shows various estimates for the internal rates of return (IRR) of different intervention projects from a 2019 systematic review. The horizontal lines represent different estimates with the lengths showing the period of the intervention. The conclusion from the research was that "The cost benefit and cost effectiveness of onchocerciasis interventions have consistently been found to be very favourable."

By way of comparison, a good real estate investment project would have an IRR of 20%.

However, as well as the local economic benefits there were also some benefits to the drug company Merck. Alex Edmans points out in his book 'Grow the Pie' that MDP had a big impact on Merck's positive reputation.

"Fortune named Merck America's most admired company for seven years in a row between 1987 and 1993, a record never equalled before or since."

Grow the Pie, A. Edmans.

So MDP is a great example of the impact that health access can provide to a multitude, if not all stakeholders.

In sustainability health is a core social inclusion theme. Access to health care and services, health equity, health equality and social justice.

As part of our consulting role we have engaged with corporates and investors in the broader health care sector. Many firms are endeavouring to make their businesses and the impact of their businesses more sustainable.

We have not found too much confusion between health equality and health equity. Health equality assumes that everyone gets the same support regardless of their starting point, i.e. everyone gets the same treatment and access.

Another way of saying 'health inequality' is 'discrimination'. For example, the 2015 US transgender survey found that transgender adults faced high rates of discrimination and mistreatment when interacting with health care providers. A more recent survey from the Center for American Progress conducted in 2020 found that...

"40 percent of transgender respondents reported postponing or avoiding getting preventive screenings in the year prior to CAP’s survey due to discrimination, including 54 percent of transgender people of color."

LGBTQI+ survey, Center for American Progress and NORC at the University of Chicago.

Health equity on the other hand does consider starting points and is focused more on outcomes of health rather than the inputs of the service provision. In other words, everyone gets the support that they need based on their circumstances.

Note the careful wording from this research from 1993. It is not equality of health care but equality of health, i.e. starting points and disparities matter (bold emphasis is mine):

"... equality of health should be the dominant principle and that equity in health care should therefore entail distributing care in such a way as to get as close as is feasible to an equal distribution of health."

Equity and equality in health and health care, Culyer and Wagstaff, 1993

In addition to providing the support that disadvantaged people or communities need, a further step would be to lower or remove the barriers that create that inequity in the first place. This is the concept of social justice and is a holistic viewpoint.

We shall look at some examples later.

In my conversations with health care companies an area where I have found terms sometimes used interchangeably is in sustainability strategy and reporting. Typically it is between 'health access' and 'health equity'.

'Health access' is a component in achieving health equity. Health equity brings together a number of disciplines beyond just health access and health care and has positive outcomes beyond just health.

What is health equity?

Health is a fundamental right. Indeed the highest attainable standard of health is a fundamental right. Don't take my word for it. It is in the World Health Organisation Constitution:

… the highest attainable standard of health [is] a fundamental right of every human being.

World Health Organisation Constitution, 1946

It is one of the UN's Sustainable Development Goals to promote that right.

Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

UN Sustainable Development Goal 3: Good health and well-being

The WHO went further in defining what health equity is.

Health equity is achieved when everyone can attain their full potential for health & well-being.

World Health Organisation

It is quite a broad definition. Let's look at it the other way around. What are the factors that can prevent people achieving their full potential for health and well-being? What are the differences between different people? What are the disparities?

Health disparities are a function of not only access to health care, but also the social determinants of health that directly and indirectly affect the health, health care, and wellness of individuals and communities, including:

- the environment

- the physical structure of communities

- nutrition and food options

- educational attainment

- employment, socioeconomic status

- race, Ethnicity

- sex, gender identity

- geography

- language preference

- immigrant or citizenship status

- sexual orientation

- disability status

US Health Equity and Accountability Act of 2022, Title X, sec 10001

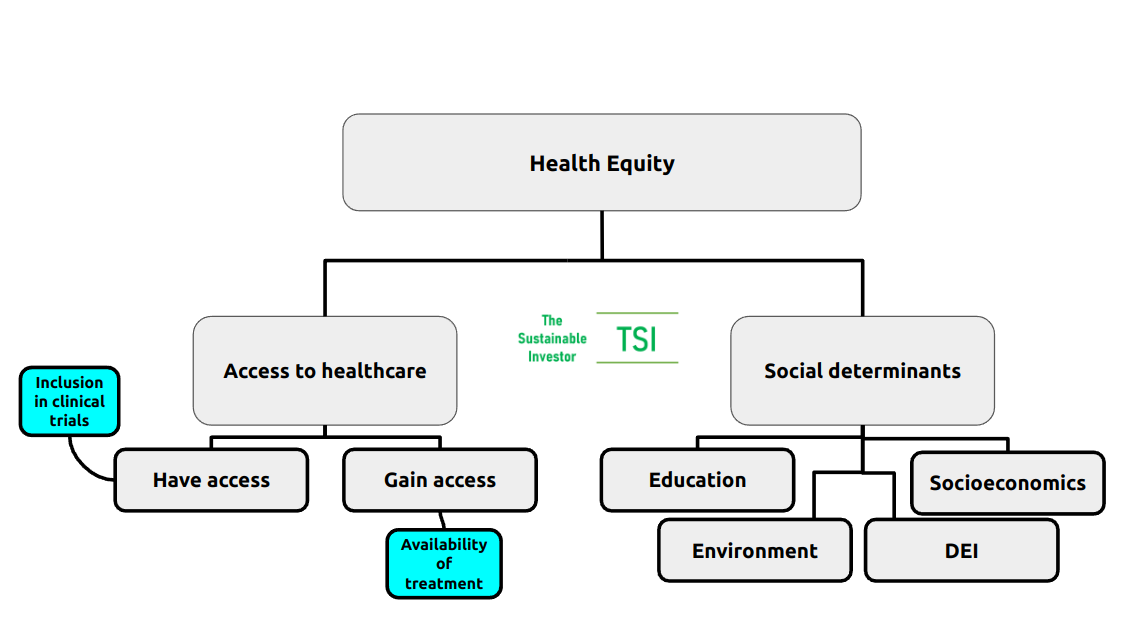

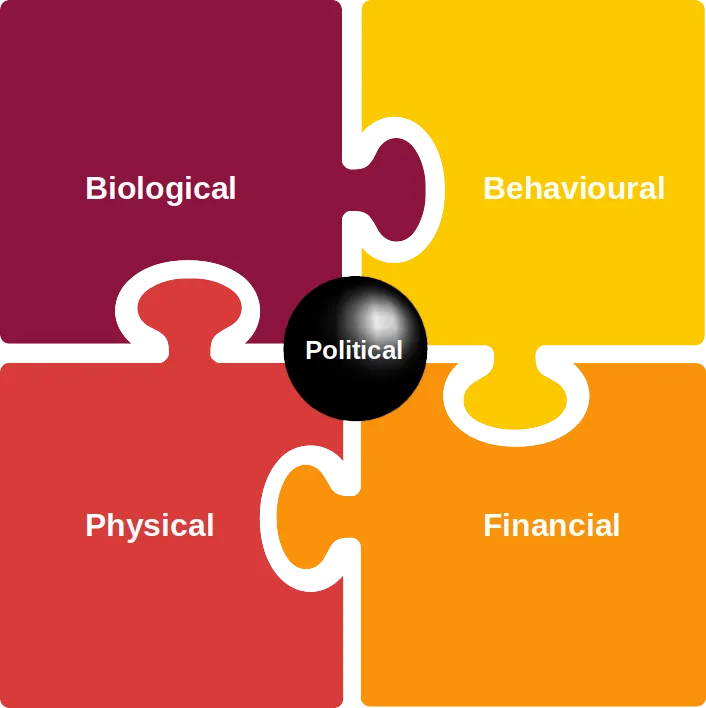

Taking all of the above into consideration, we arrive at the following overview:

We shall look at each of these areas in more detail later in this blog, but a couple of clarification points.

Under 'Access to healthcare' I have separated out 'Have access' and 'Gain access' - the latter is more about delivery of health services including medication and procedures, whilst the former is really about services existing for any given community or demographic. That starts with understanding the particular needs of communities and their involvement in drug trial and discovery.

An important aspect of developing health equity is effective monitoring. This is one target of UN SDG 3: Good health and well-being:

"Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks."

UN SDG3 Target 3.d

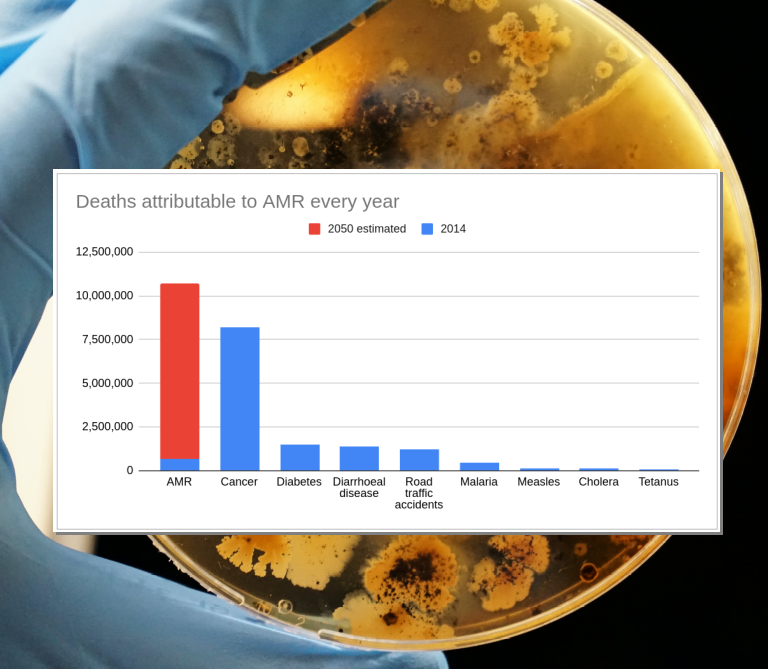

Interestingly, one of the indicators for Target 3.d is the "percentage of bloodstream infections due to selected antimicrobial-resistant organisms." Regular readers will know that 'antimicrobial resistance' (AMR) is a topic we have written extensively on.

We discussed a review of national action plans (NAPs) on AMR conducted by researchers from the Global Health Governance Programme at the University of Edinburgh. They found that NAPs were particularly lacking in education, accountability and feedback mechanisms - i.e. monitoring. Effective monitoring can improve policy direction and implementation over time. Link to blog 👇🏾

Why do we care about health equity?

A 2022 actuarial study by Deloitte concluded that health inequity in the US accounted for roughly US$320 billion in annual healthcare spending potentially ballooning to more than US$1 trillion by 2040 if that inequity was not addressed.

As well as the obvious direct link to UN SDG goal 3, health equity can support and be supported by the other UN SDGs too. The social determinants of health, as mentioned previously, are clear across goals 1-11. Goal 11 itself, "sustainable cities and communities" is particularly pertinent in bringing many social determinants together.

With health equity come broader benefits to society as a whole. Life expectancy rises and importantly productive life expectancy rises. That brings with it greater income levels, improvements in the local economy, education and attainment. Consider the improved ability of farmers unencumbered by river blindness.

Incapacitation and death can be caused by disease or injury but also through the impacts of the social determinants of health. And inequity is present and impacts both the developing and developed world.

In England for example, there is a 19-year gap in healthy life expectancy between the most and least affluent areas of the country.

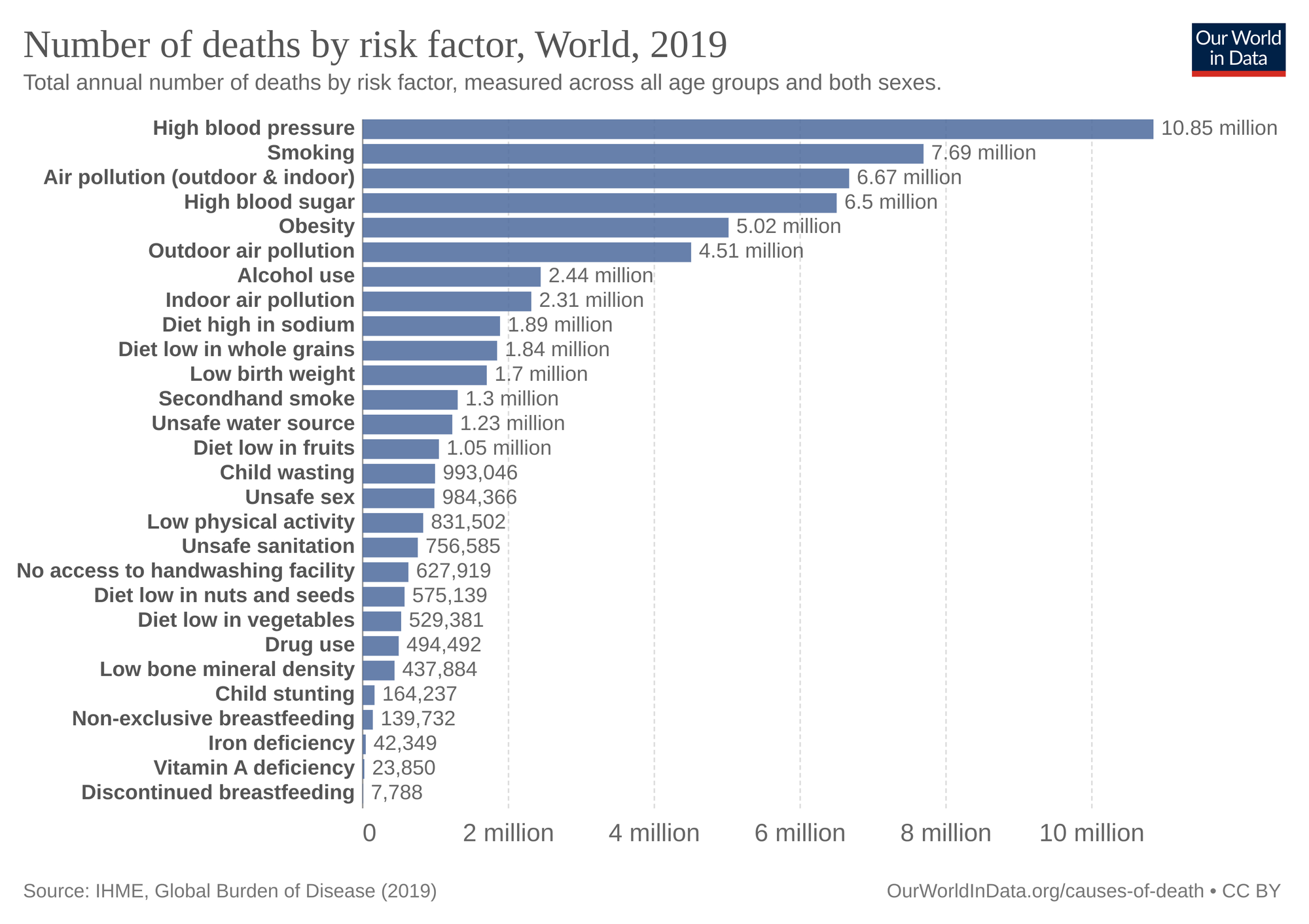

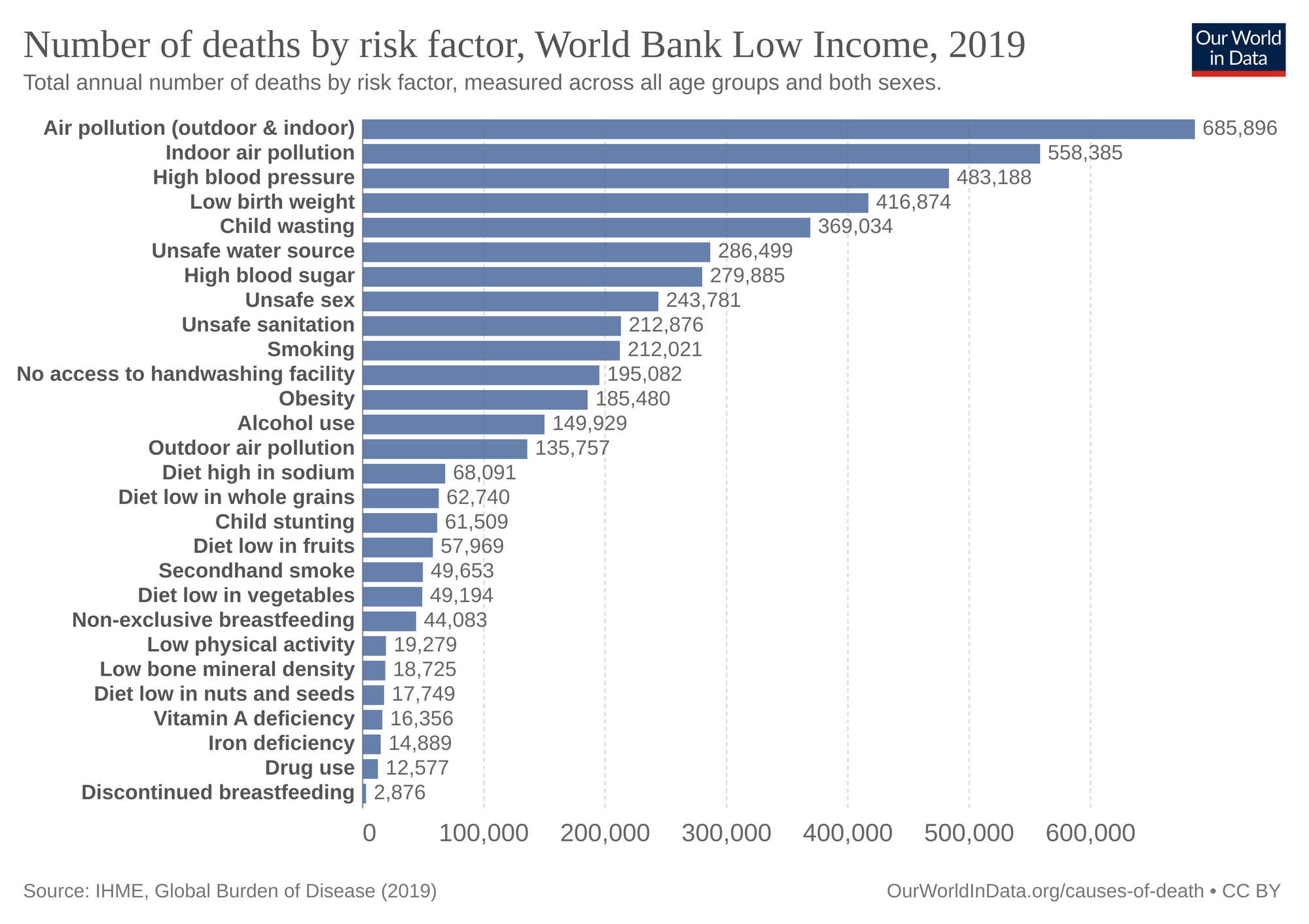

Looking at risk factors having the most influence on the number of deaths, air pollution, diet (particularly from lack of economic access to nutritious food), and access to clean water and sanitation are key.

... and particularly so in low income countries:

In July 2022, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution establishing the human right to a "clean, healthy and sustainable environment" as part of a wider range of human rights guaranteed by the body. Whilst not legally binding, it is hoped it will act as a catalyst for positive change.

So health equity is a cross-cutting theme that has its solutions and drivers across all industries.

In the remainder of this blog we shall look at social determinants of health, focus in a bit more on health access looking at big pharma, value-based pricing as well as some innovations that are improving access.

Let's dive into this in more detail...

Social determinants of health

When I was growing up, one of my favourite TV programmes was 'Record Breakers' which featured the charismatic host Roy Castle. He was also a very talented jazz trumpeter who sadly passed away from lung cancer at the age of 62. Cigarette smoking has been linked to between 80% and 90% of lunch cancer deaths. Only problem is, Roy Castle was not a smoker. He blamed his illness on passive smoking during his years of playing the trumpet in smoky jazz clubs and after his death his widow Fiona campaigned for a smoking ban in pretty much all enclosed public spaces which came into effect in the UK from 2004 to 2007 and remains in effect today. In the ten years since the ban, the number of smokers dropped by almost 2 million and almost 40% of respondents to a cancer research UK poll believed that the ban had helped protect the next generation from taking up smoking.

The environment, particularly air pollution is an important determinant of health. A law requiring Massachusetts to assess the social impact of projects alongside environmental risks, particularly the effects of pollution levels on residents, came into effect in 2021. The law defines the vulnerable "environmental justice communities" disproportionately affected by pollution through virtue of race, income and English-language proficiency. The aim is to increase communities’ ability to advocate for their needs with regard to potentially damaging infrastructure projects. The law will also make it harder for fossil fuel projects to be sited in communities with a larger proportion of residents of colour, although it doesn't impact existing projects.

Illness tends to know no boundaries be they geographical, gender or race but how different races and genders respond to treatment can vary. Diversity in drug trials has historically been an issue. Analysis of clinical trial data by researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston found that despite 51% of cancer patients are female, just 41% of clinical trial participants were female.

Older Black and Hispanic Americans are twice and 1.5 times as likely, respectively, to have Alzheimer’s than their white counterparts, but the majority of clinical trials feature only white patients. OutreachPro is a programme designed to help research increase awareness of and encourage participation in Alzheimer's studies.

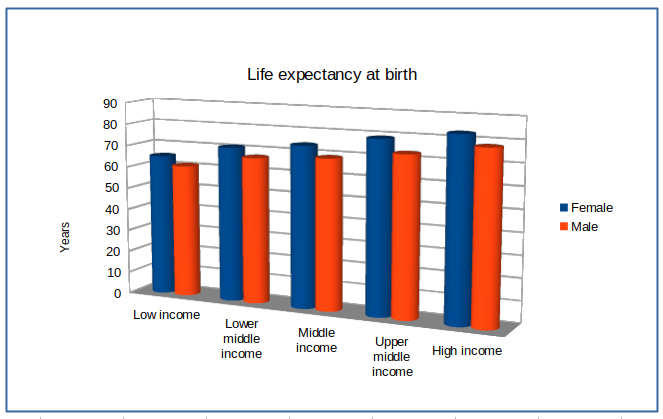

Socioeconomics play a big part in health. Look at life expectancy relative to income levels:

Income levels can determine access to nutritious food which in turn can have impacts on health. We saw in an earlier chart how important a risk factor in death that obesity and malnutrition are. Whilst there is a well-established link between diet and physical health, especially for non-communicable diseases such as Type 2 diabetes, Coronary Heart Disease and some cancers, the link with mental health is less well known. For example, University of Otago, New Zealand researchers found that higher intake of fruit and vegetables are associated with better mental health.

Education is important in helping people understand the implications of symptoms and be aware of both self-help measures but also when to seek out assistance and health care services. And the reverse relationship is also true. Health is a prerequisite for education.

There are many examples of the multiplier effect of addressing social determinants of health, but I'll finish up on this one from the UK. Refuge provides specialist domestic violence services in the UK supporting thousands of women and children, helping them to rebuild their lives after suffering violence and abuse. Returns come in the form of safety, social and economic well-being and improved health. It is estimated that for every £1 invested, £8.24 in social value is created. Link to blog 👇🏾

So we can see that there are examples where addressing the social determinants of health can have big leveraged impacts on overall health and the ability for individuals to attain a good level of health.

In many cases it isn't even pharmaceutical companies. But what about them?

Focus on Big Pharma

An obvious area for the big pharmaceutical companies to support bringing about health equity is through providing greater access for their products - largely drugs and medical consumables.

However, the WHO also believes that the health sector has a broader responsibility that encompasses all of the components of health equity:

Evidence-informed action is needed by the health sector:

(1) to ensure high-quality and effective services are available, accessible and acceptable to everyone, everywhere when they need them;

(2) to act on the wider structural determinants of health to tackle the inequitable distribution of power and resources, and to improve daily living conditions; and

(3) to take the lead in monitoring health inequities through monitoring health outcomes and health service delivery – as well as working with other sectors to monitor people’s living conditions.”

World Health Organisation

Broadly speaking all of the majors appear to be addressing all of the above areas to varying degrees but not necessarily in a connected fashion. For example there may be environmental initiatives to cut back on carbon emissions from own operations and of course these will have a high level contribution to improving the overall environment. But the connection is not often made to enhancing broader health equity.

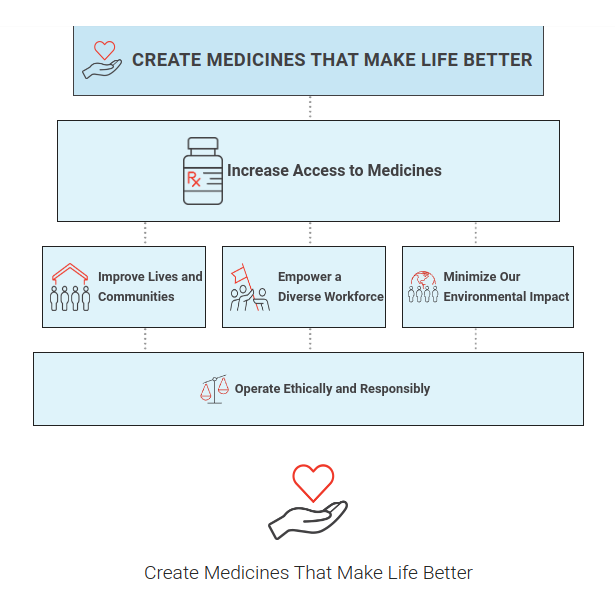

The most joined up that we have come across is Lilly. The 'Lilly 30x30' programme aims to improve access to quality health care for 30 million people living in settings with limited resources annually by 2030. You can see that whilst their starting point is increasing access to medicines, they do have some of the wider determinants of health in there too, although I would prefer to see 'Health Equity' as their top box.

Health access

As described above, the big pharma companies are very focused on improving health access with all of them having some defined strategy with the majority having direct board-level responsibility.

The WHO monitors health inequality more broadly and as we have mentioned earlier, the health equity impacts of action by health and other sectors.

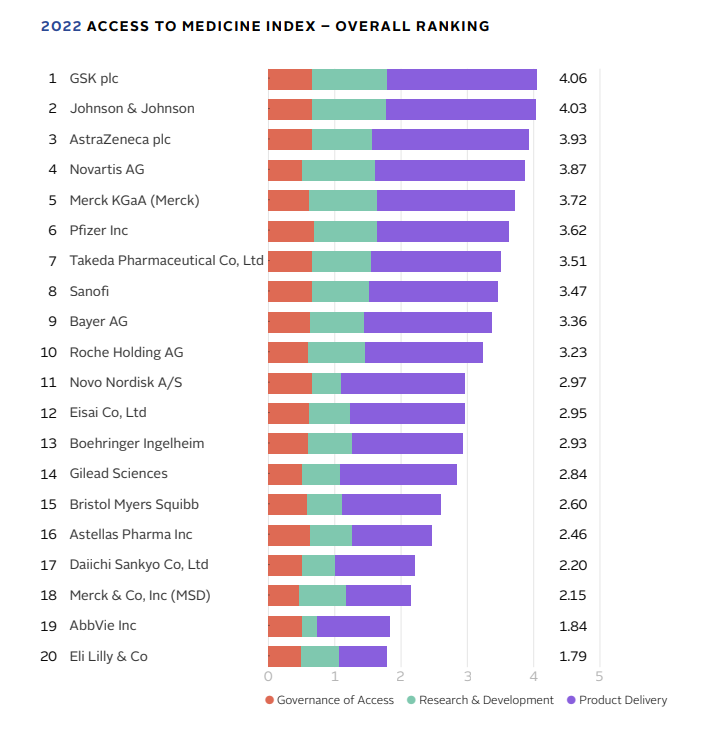

Another organisation that is helping to drive improved access is the Access to Medicines Foundation. They are focused on improving access to people living in low-and middle-income countries (LIMIC). Their funders include the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Wellcome Trust, AXA investment managers and a number of high profile philanthropic organisations. Their 'Access to Medicine Index' which assesses, scores, and ranks companies on their access-to-medicine performance and where they can improve, is now closely followed by boards, investors and other stakeholders. They are scored on their governance (do they have a strategy), R&D (are they developing drugs for diseases particularly impacting vulnerable communities) and Product delivery (can people actually get hold of the drugs?) Here are the latest rankings from 2022:

There is a reporting and disclosure imperative too which in turn is focusing investor (and other stakeholder) attention. Investors can thus be important drivers for change here.

However it does highlight a drawback of the approach that is being taken to sustainability disclosure more broadly. Themes are considered as fitting into either 'Environment', 'Social' or 'Governance'. For the SASB index reporting framework and indicators the focus is more on access and affordability than it is on the high level theme of health equity and so one rarely gets a consolidated view. The Lilly example from earlier gets closest.

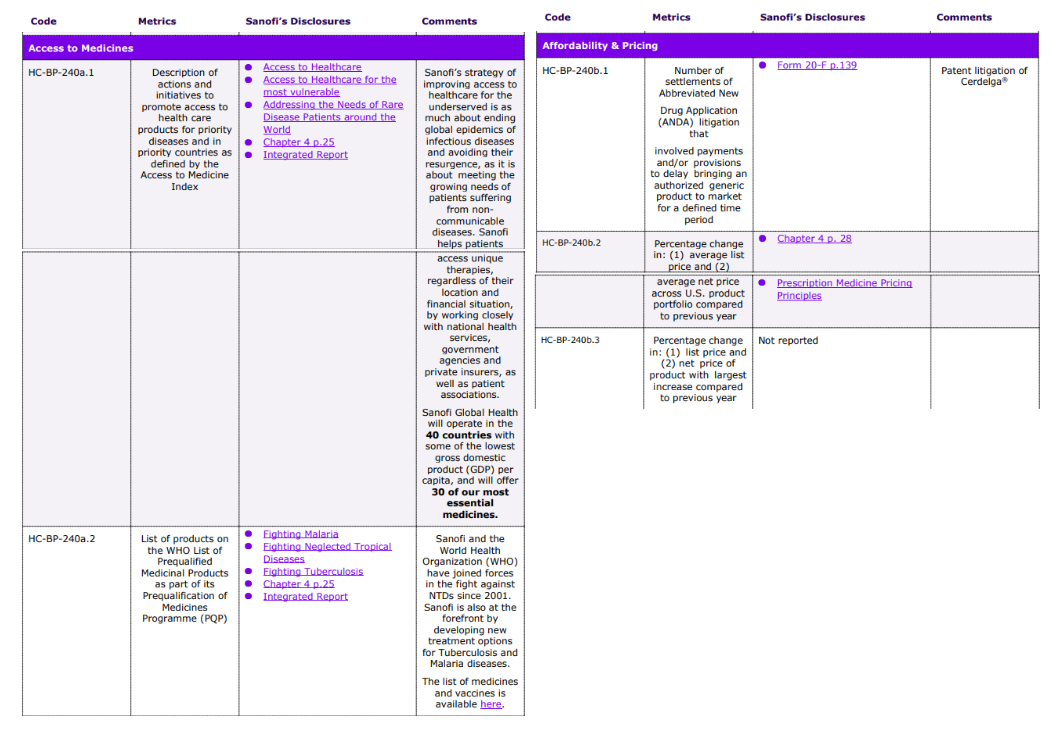

Here is an extract from Sanofi's 2021 report, as an example (note that because of the pagination on the pdf I had to cut and reassemble the table!):

In general the 'Access to Medicines' category is focused on LIMIC whilst the 'Affordability and Pricing' is focused on developed markets.

How do drug companies price their drugs? How do drug companies make money?

Value-based pricing

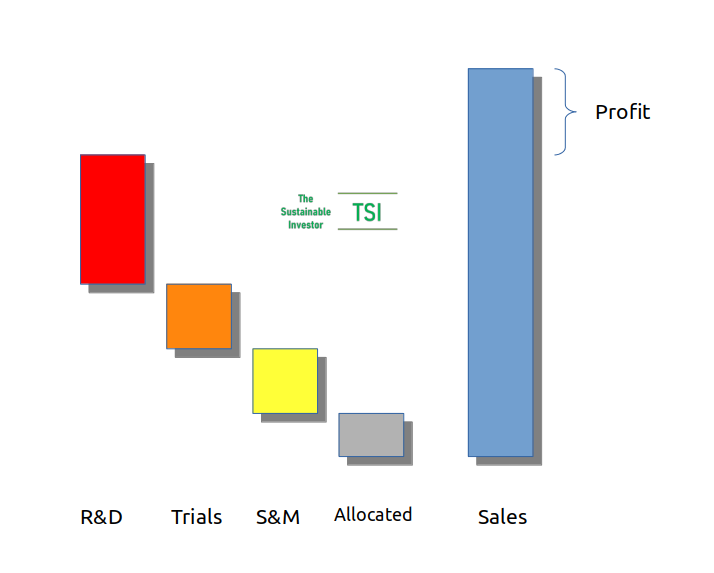

The traditional model is a consumption-based or market driven model. Essentially companies spend money researching and developing new drugs, trialling them to ensure they show efficacy (i.e. they work) and that they do not have intolerable side effects. They will then spend money marketing the drug and distributing the drug as well as incurring the normal overheads of running a business. The hope is that upon launch they will recover those costs over a period of time based on sales of the drug. In other words that recovery is dependent on three factors: how many drugs they sell, at what price and for how long?

The 'how long' is typically a function of the patent protection that the company has over the main compound in the drug and in some cases how the drug is delivered to the patient (tablet, nasal spray etc).

In the US prices of prescription drugs are set at whatever they believe the market will bear. That can become a problem when it is a 'must-have' drug treating a chronic condition. The worst example of this was Turing raising the price of Daraprim, a drug used for treating toxoplasmosis, by almost 5,500% from US$13.50 per tablet to US$750 per tablet pretty much overnight. In addition, a Daraprim Direct program was set up effectively creating a closed distribution system for the drug. The CEO of Turing, Martin Shkreli argued that this system could prevent generic competitors from legally obtaining tablets for bioequivalence studies and ultimately the creation of competing generics.

Patents are important in protecting the economic value of a drug and allowing the pharma company to recover their costs and generate a reasonable return for stakeholders. However, sometimes that can be abused. One such example is the so-called 'patent thicket' where multiple patents are filed beyond the primary patent that covers a key drug compound making it legally very resource intensive to challenge. This is effectively increasing the life of the economic life of the drug for the developing company and preventing generic versions from being produced. Generics are bioequivalent to the original - the medicine works in the same way and provides the same clinical benefit - and are typically significantly cheaper than original compounds and are therefore inherently more economically accessible. A report by advocacy group I-Mak pointed out that seven out of ten of America's best-selling drugs have primary patents set to expire this decade.

A group of ethical investors are proposing enhanced disclosure on this strategy with a number of companies including, ironically, Merck. There are real differences between the US and Europe with four times as many patents granted on the top ten drugs in the US compared with Europe on average - Humira, an arthritis drug by AbbVie, has 6.4x as many patents.

Pricing models also vary by country. Germany and Australia, for example, use a value-based pricing model instead. What is value-based pricing? The York Health Economics Consortium has a good definition.

"Value based pricing is a pricing strategy which sets prices primarily according to the perceived or estimated value of a product or service to customers rather than according to the cost of developing the product or its historical price."

Value Based Pricing [online]. (2016). York; York Health Economics Consortium; 2016.

US drug prices are two to four times higher than prices for those same drugs in Australia, Canada and France and nearly 30% of American adults reported not taking medicines as prescribed in 2019 due to cost.

With consumption-based pricing, one other issue that can arise is that areas of R&D investment do not necessarily reflect health needs of the population. Antibiotics are a good case in point. With AMR as such a key threat, why are we not just creating new and different types of antibiotics? What’s the problem?

The problem with antibiotics is that many are genericised and so pricing is low, but also, for good stewardship reasons (to slow down the development of resistance), doctors are reluctant to prescribe them, hence consumption is low. As a result, over the last 10 years, the average revenue for an antibiotic has been just $50 million which is just not enough and as a result investors have fled the antibiotics field.

Dr John Rex highlights the issue and the importance of a value-based pricing approach using household fires as an analogy.

"The fire department isn’t paid per fire. You don’t buy a fire extinguisher as the fire is breaking out."

Dr John Rex, AMR Solutions

Two models that have been developed to incentivise new antibiotic development are the UK NHS subscription style payment model and the Pasteur Act of 2021 in the US, although the latter is still being debated.

With the NHS model the drug development company is paid based on the value of the product to the NHS (calculated looking at savings from overall healthcare, etc) rather than how much of the antibiotic is actually consumed which avoids the conflict with good stewardship.

If you want to find out more about AMR, then read this primer 👇🏾

Innovations

Finally let's look at some innovations that have improved the access to healthcare around the globe, particularly in remote and climatically harsh locations.

Back in 2018 UNICEF, Australian drone company Swoop Aero and German drone company Wingcopter started testing the delivery of vaccines to remote areas. The location, the Pacific island nation of Vanuatu wanted to increase vaccine coverage from the then 80% to 95%. In 2019, Wingcopter also delivered a Diabetes medication dose autonomously in the Aran Islands in Ireland carrying back blood samples so that more accurate diagnoses can be found.

Johnson and Johnson also funded a trial delivering HIV medicine by drone in Uganda to rural hamlets in Kalangala, an archipelago in Lake Victoria. An estimated 27 percent of the islands' population is infected with HIV. The trial was run by the Infectious Diseases Institute.

More accurate tools at affordable cost can also help to bring more effective health care to more people. For example the 'paperfuge' developed by the bioengineers at Stanford in 2017 is an ultra low cost centrifuge used for separating out components in blood, which is an important step in diagnostics. At a cost of around US$0.20 it has been used in LIMIC particularly for detecting malaria parasites. More recent tests on other uses have proved successful.

Finally, of course new treatments developed for infectious diseases which remain some of the biggest killers in LIMIC bring huge benefits by removing a dominant underlying condition in much the same way that river blindess was for those particular countries. This can allow those populations to increase their overall base-level of health and well-being. Malaria is one area where such innovation has been most promising. Link to blog 👇🏾

Conclusion

So health equity is a cross-cutting theme that has its solutions and drivers across all industries, not just pharmaceuticals. It is about providing the ability for people to attain the highest attainable standard of health regardless of their starting point. It is about equity and it is about social justice. To meet all of the sustainable development goals will require solutions that address environmental, social and economic problems. But the benefits will also be felt across all of those areas.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.