The green hydrogen investor dilemma

Is the growth potential more than just hype and can companies grow profitably? Focus: Green hydrogen, heavy industry, hard to decarbonise, steel, chemicals, fertiliser, ammonia

Summary: One of the big challenges for investors in analysing industries that have massive growth "potential", is disentangling what is hope from what is likely. And if the growth potential is not just hype, working out if companies can actually grow profitably. We argue that green hydrogen is a classic example of this challenge.

Why this is important: We can see a great future for green hydrogen as an industrial feedstock, replacing existing hydrogen produced with fossil fuels and acting to assist in decarbonising industries such as chemicals and steel.

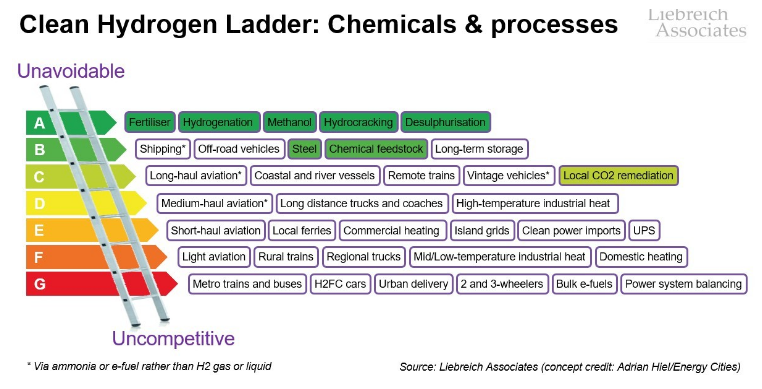

The big theme: Green hydrogen is often portrayed as the Swiss army knife of energy sources, something that can turn its hand to almost any application. And as a result, many studies forecast a massive surge in demand. But as Michael Liebreich so eloquently expresses in his Clean Hydrogen ladder, some uses make sense, but for many applications, we actually have better alternatives. Yes, demand will probably rise strongly, many of the "best" applications are in heavy industry - which has material implications for which companies will create and retain value.

The details

The green hydrogen investor dilemma

One of the big challenges for investors in analysing industries that have massive growth "potential", is disentangling what is hope from what is likely. And if the growth potential is not just hype, working out if companies can actually grow profitably. We argue that green hydrogen is a classic example of this challenge.

Yes, it could become an enormous industry, meeting most of our energy needs. But that doesn't look like the most likely outcome, with many applications containing a fair bit of hype. Realistically, we expect green hydrogen to replace existing "dirty" hydrogen, plus over time become a major industrial feedstock. To be clear, this is still a massive market, but this balance of end markets has a big impact on what will make a successful company for investors.

An article in Hydrogen Insight (31st October 2022) quotes the Rystad Energy senior sector analyst Lein Mann Bergsmark saying that "some hydrogen electrolyser makers will go bankrupt this decade amid brutal over supply. They face tough choices, expand too slowly and risk losing out on gigawatt scale orders; expand too fast and risk failing to sell equipment from expensive gigafactories that are operating at sub scale".

Their argument is simple. While electrolyser manufacturers are ramping up supply, based around machines built in expensive new gigafactories, their potential customers are holding back on firm orders. This is creating a massive overcapacity that is likely to end up putting manufacturers in a tight spot. Mann Bergsmark compared the announced plans for electrolyser manufacturing expansion with announced green hydrogen projects globally, and their respective dates for build-out. Her conclusion was that demand will hover around 30-40% of available production capacity from 2024-30.

There is a clear rationale for electrolyser makers to scale up production ahead of the demand curve. Not only do they want to be ready to supply large orders when they come in, but economies of scale — particularly with large automated or semi-automated factories — will bring down production costs, potentially enabling them to undercut rivals and win more orders. So, it's a bit of an arms race.

How big can the green hydrogen market really become?

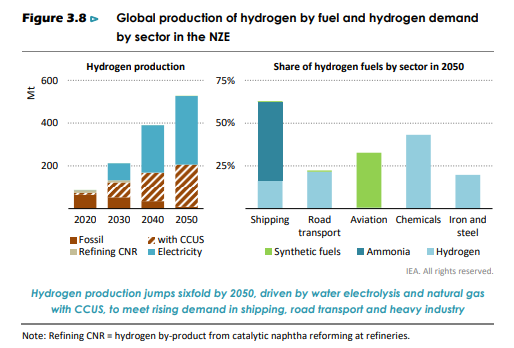

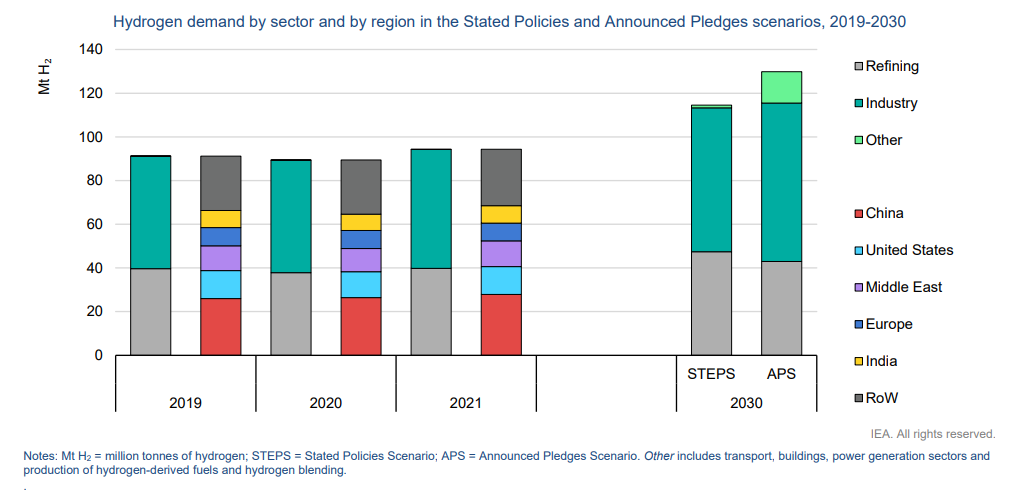

There have been lots of studies, but the IEA Net Zero by 2050 report is the one that gets quoted the most (known as NZE). This "forecasts" that under their net zero 2050 scenario, total hydrogen demand increases almost sixfold from c. 90 Mt in 2020, to 530 Mt in 2050. Roughly half of this is used in heavy industry (mainly steel and chemical production) and in the transport sector. Almost all of this is low carbon, at c. 60% from electrolysis and 40% using Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS). Global electrolyser capacity reaches 850 gigawatts (GW) by 2030 and 3,600 GW by 2050, up from around 0.3 GW in 2020. So, this looks really encouraging from an investment perspective.

And this is mirrored in commentary from Bank of America Global Research who said in a September 2020 (publicly released) report, "over the coming decades, you could see green hydrogen playing a role in heating our homes and powering fuel cells for our cars, trains, ships and planes".

But - investors need to remain cautious

There are four issues to watch, how realistic the base scenarios are, the existence of better alternatives, the time before some applications become real, and where in the value chain might competitive advantage be found?

Scenarios matter. If instead of the NZE you take as your base the IEA STEPS scenario, based on countries stated policies, or even the more optimistic Announced Pledges scenario (all pre COP27), the picture for total hydrogen demand looks different. Instead of 200Mt of hydrogen demand by 2030, its +/- 120Mt. And nearly all of it (bar the pale green bar in the APS scenario) is for refining or industry.

Why - because better alternatives to green hydrogen exist. As Michael Liebreich so eloquently expresses in his Clean Hydrogen ladder, now on version 4, some uses of hydrogen make sense, but for many applications, we have better (electrification) alternatives. Anything below say C on the ladder looks unlikely - so from the IEA Net Zero emissions scenario above, we should probably discount road transport, plus home heating and short haul aviation (among others).

And then there is when does this happen. If we take shipping, that very big bar in the NZE scenario, to get to green ammonia, we need green hydrogen at scale, and a lot of new investment, including upgrades on ship propulsion systems. So best guess for it being available at scale - think next decade. Which starts to make the more conservative IEA scenarios look more realistic, with slow demand growth over the next decade and then starting to ramp up in the 2030's and 2040's. Still a very investible theme, just one with quite different dynamics.

And finally, coming back to the Rystad Energy senior sector analyst Lein Mann Bergsmark and her caution - we wonder about where competitive advantage will sit by say 2030. If most of the end demand comes from large scale industrial processes, if the technology is well understood, and if large competitors have been attracted into the industry (which is what IRENA's three stage industry development model expects), then will the advantage lie with the large industrial gases and chemicals companies, rather than the specialist electrolyser manufacturers? Plus - where might China be in terms of cost and scale advantage by then?

Overall, even when we cull out the hype, we can see a great future for green hydrogen as an industrial feedstock, replacing existing hydrogen produced with fossil fuels and acting to assist in decarbonising industries such as chemicals and steel. And given that its growing off a very small base, with a less than 5% market share, y/y growth will be strong. Our note of caution is more about where the industry winners, from an investing perspective might be found.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.