Going all out and the risk of inadvertent greenwashing

Greenwashing is not always malevolent. As Boards shift their focus to include a broader range of shareholder interests, they need to be sure they understand what 'additionality' they are actually providing.

Summary: An over focus on aggregate scoring brings with it the risk that a business tries to go all out and address everything rather than focusing on the relevant and the possible. That brings with it the danger that a business falls into the trap of inadvertently greenwashing. Strategic decision-makers, investors and communicators need to consider the 'additionality' of their sustainability initiatives as well. We look at additionality with regards emissions and scope3 but also how it applies in diversity and inclusion. We take a look at some greenwashing issues to think about with investment products including briefly touching on the FCA regulations being proposed.

Why this is important: Stakeholders from investors through to people in the community at large are becoming less enthralled with offsetting as a primary measure. They want to see additionality in an organisations actions. And communication that matches those actions, not oversells it.

The big theme: As a broader group of stakeholder interests have come to the fore including employees, customers and the community at large there has been a shift in thinking from not just considering the impacts 'of' the environment, social and governance aspects and how they impact a business but also the impact of the business 'on' the environment and society as a whole. In other words, considering the business as part of a broader ecosystem. With that in mind, if businesses understand how they fit into that ecosystem and the materiality and relevance of their actual and potential impact, they can be the most effective and avoid the traps of inadvertent greenwashing. They can be genuinely additional, both in terms of return and the sustainability transition.

The details

In a previous blog, 'Double materiality: the 'on' and 'of' switch', I highlighted that the concept of relevance sits hand-in-hand with materiality. For something to be material it has to matter to the business and its stakeholders. It has to be relevant.

Double materiality reflects a shift in thinking from not just considering the impacts 'of' the environment, social and governance aspects and how they impact a business but also the impact of the business 'on' the environment and society as a whole.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals were designed to encompass all of the various facets in the route to bringing "peace and prosperity for people and the planet." The aim was a shared or collective plan where the planet is thought of as a complete ecosystem.

That aim is something increasingly embraced by investors and other stakeholders at the organisational level. We need to start thinking about organisations and businesses as part of a broader ecosystem that includes people and planet.

Rather than 'Enterprise Value' or 'EV' we should be thinking about the bigger picture, the whole pie. As Professor Alex Edmans espouses in his seminal book 'Grow the Pie', the primary goal of a company should be to serve society rather than generate profits. This approach "enables investments to be made that end up delivering substantial, long-term pay-offs." It's not to say that profits don't matter, its more that by focusing on meeting the wider needs of society, profits are a result, not an objective. In other words it is not just worthy, it is good business. Thinking about that bigger picture is good business.

However, ESG investing adopting a largely data and scoring driven approach has taken a more unidirectional materiality approach. In particular, aggregate scoring brings with it the risk that a business tries to go all out and address everything rather than focusing on the relevant and the possible. That brings with it the danger that a business inadvertently greenwashes.

Strategic decision-makers, investors and communicators need to consider the 'additionality' of their sustainability initiatives as well. Stakeholders from investors through to people in the community at large are becoming less enthralled with offsetting as a primary measure.

Before we investigate that, let's start at the beginning. What is greenwashing?

What is Greenwashing?

Greenwashing involves giving a misleading or false impression of how environmentally friendly an organisation's actions are. The term is thought to have been coined by an environmentalist Jay Westerveld who paraphrased the term 'whitewashing' (deliberately attempt to conceal unpleasant or incriminating facts) to refer to the practice of hotels asking guests to "Save Our Planet" by reusing towels (place on the rack to reuse; place on the floor to get it replaced). However Westerveld saw it as more about saving on laundry and linen costs for the hotel given that there were plenty of other areas where the hotel was being less than environmentally friendly.

A high level problem of greenwashing is the building of scepticism about claims made by corporates and organisations in general not only about environmental issues but other sustainability and ESG concerns ('social washing', 'pink washing' or 'blue washing' but really the concept is the same).

Sometimes that greenwashing is malicious, a deliberate deception such as the Volkswagen emissions testing scandal where the company had intentionally programmed TDI diesel engines to activate their emissions controls only during laboratory emissions testing.

Greenwashing can also be accidental or unknowing. The ILO estimates that 170 million children are involved in child labour making textiles and garments to satisfy the demand of consumers in the developed world. A company outsourcing production may feel that aspect is 'no longer their responsibility' and hence they can focus on what they now control. Increasingly there are moves to include impacts from entities in an organisation's value chain into the disclosure. The most common one is scope 3 emissions. The Lieferkettengesetz or German supply chain law seeks to hold companies to account for human rights abuses within their supply chains.

Sometimes claims can be well intentioned but with targets that are too far out in the future or too generalised. Specifics are important. Although if you are specific, you had better be right and be able to back up your claims.

On the same day in June of 2022, the UK Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) made two significant rulings under the Green Claims Code. Both rulings involved major supermarket chains and both supermarket chains made the same claim: "a plant-based diet is better for the planet and our health." However the ASA found in favour of one (Sainsbury's) but not the other (Tesco). So what's going on there? As Jane Shaw pointed out in her excellent article, Sainsbury's had made general statements which are based on scientific consensus, whereas Tesco had made claims relating to a specific product in its Plant Chef range. The truth was not the issue in this case. Tesco had no evidence to substantiate their claim.

Trying to be all things: the danger of being too data-led

Even as the world has become increasingly aware of the significance of environmental and social factors and the governance required to manage those risks, ESG investing has emerged with, in effect, that same EV approach, relying on data and scoring to assess how exposed a company is to ESG risks.

In 'Double Materiality: the 'on' and 'of' switch' I highlighted the major ESG metrics and ratings providers' messaging as being focused on impact and risk to the business - an EV approach.

Back in November of 2019, I wrote about ESG metrics in a blog for IR Magazine, 'Preparing for emergent themes in ESG' in which, amongst other things, I discussed a couple of limitations of ESG ratings and metrics. One of those was the "static nature implicit in most ratings systems" and the concern that "ratings are often backward-looking, considering what management teams have done historically and not necessarily taking into account steps they are taking to improve their impact." I still maintain that is, in the most part, a limitation. I also talked about lack of standardisation or how there was no consistency between ratings agency scoring of the same companies. However, in recent years I have found arguments from experts such as Professor Alex Edmans persuasive.

He points out that many ESG factors are hard to measure quantitatively and that in essence ratings are an opinion. It is therefore perfectly expected that "reasonable people can disagree – just as some equity research analysts will rank a company as Buy and another as Sell."

The issue of aggregation remains. That is not a problem of ESG metrics and scoring but rather of how they are used. Aggregate scoring brings with it the risk that a business tries to go all out and address everything, striving for a better score by scoring highly on every metric, rather than focusing on the relevant and the possible. That brings with it the danger that a business inadvertently greenwashes.

Focusing on what is important and relevant can help guard against inadvertent greenwashing. Rather than attempt to address or demonstrate that an organisation is addressing all of the UN SDGs, is it better to focus on the few that can best be addressed by the business and relevant to all of its stakeholders?

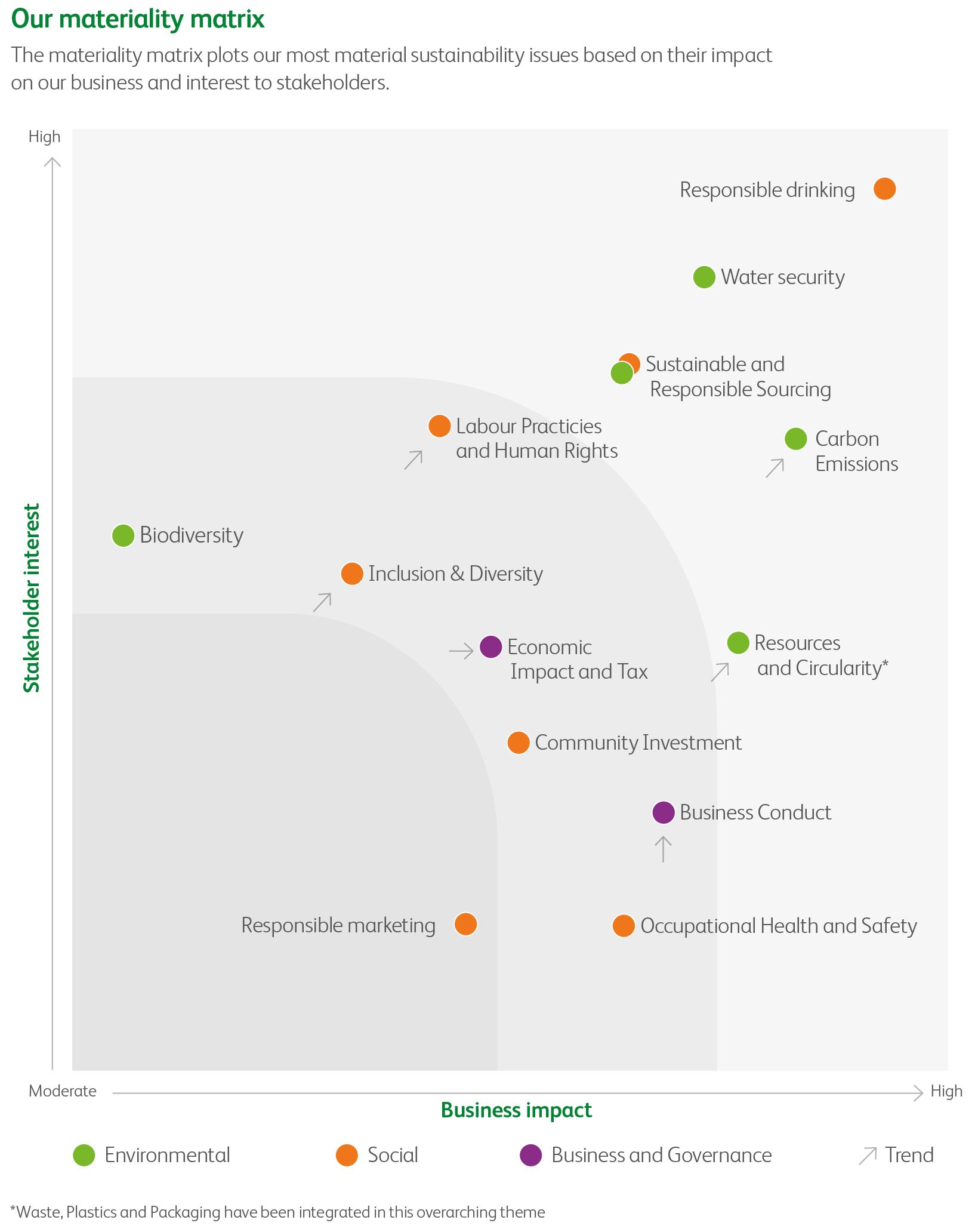

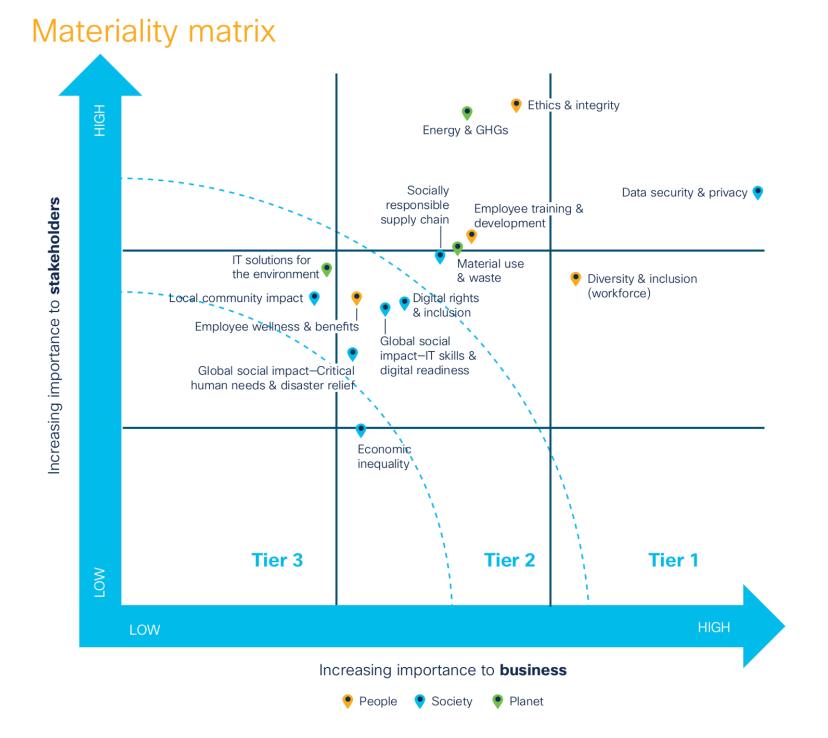

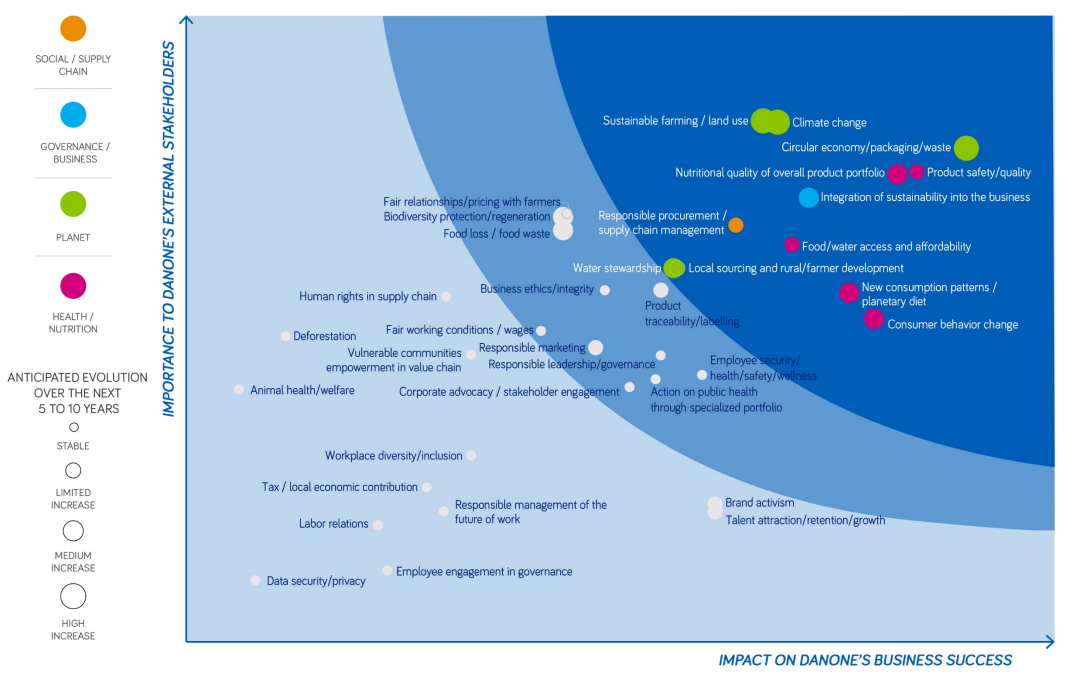

Increasingly, companies are disclosing materiality matrices to help identify and demonstrate the issues that are relevant to their stakeholders and important for their businesses. Here are a three examples from Heineken, CISCO and Danone:

If we take Heineken as an example, 'Responsible drinking' is material to both the business and stakeholders (society at large) and so one of their major initiatives created and grew the 'no-low alcohol' category which has been so successful that it is also a significant sales category at almost seven percent of brand beer volumes.

Considering relevance and importance, not only to the business itself, but to the wider group of stakeholders implies thinking of the business not as an isolated entity but rather part of broader ecosystem including people and planet.

That leads us onto another important principle: additionality.

Additionality

The Kyoto Protocol was an international treaty extending the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) committing states to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. It was adopted on 11 December 1997 and came into effect on 16 February 2005.

(a) Voluntary participation approved by each Party involved;

(b) Real, measurable, and long-term benefits related to the mitigation of climate change; and

(c) Reductions in emissions that are additional to any that would occur in the absence of the certified project activity."

[Source: Kyoto Protocol, Article 12]

Point 5 (c) from Article 12 is particularly interesting as it highlights the principle of additionality.

Michael Gillenwater from the Greenhouse Gas Management Institute defined it in a 2012 discussion paper as "a determination of whether a proposed activity will produce some 'extra good' in the future relative to a reference scenario, which we refer to as a baseline. In other words, additionality is the process of determining whether a proposed activity is better than a specified baseline."

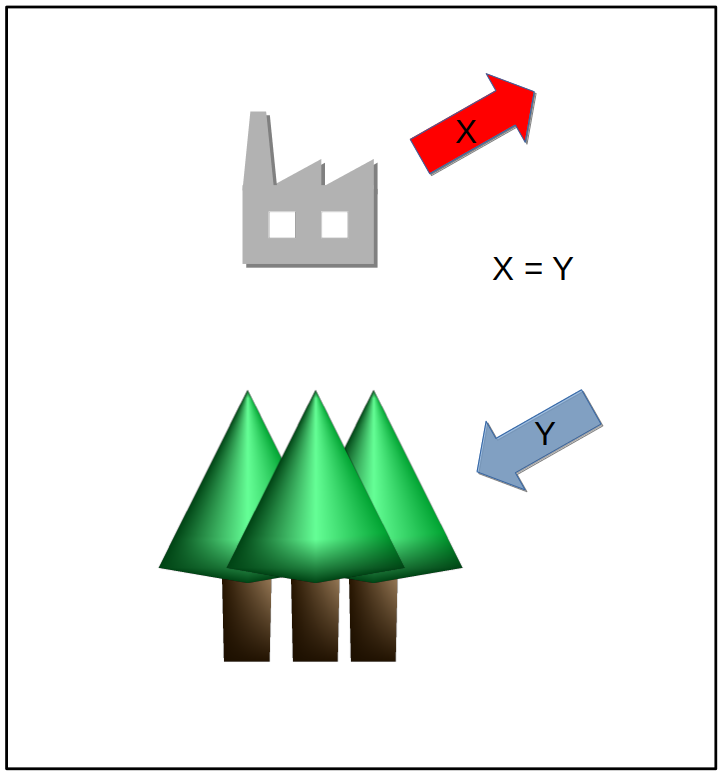

Let's take the example of a factory that is generating GHG emissions. One of their sustainability initiatives is to reduce those harmful emissions, but they are unable to physically reduce them and so have bought carbon offsets. Those offsets are in the form of an investment in a forest which absorbs CO2 from the atmosphere.

Looking at the factory in isolation, it looks like it is reducing its impact as the forests are absorbing an equal amount of CO2 to that which the factory is emitting.

However, if we broaden our view to other factories it is possible that the sum of offsets is actually greater than the level of harmful emissions that can actually be absorbed by the forest. Even worse, those forests might not actually be as big as claimed or even there at all. What about credits for projects capturing CO2 where that CO2 was then used for enhanced oil recovery - of a fossil fuel that is then burned generating new emissions?!

There has been a growing consensus that offsetting should really be used when other primary methods of reducing emissions have been exhausted and where the payment to offset is going to projects that are genuinely removing greenhouse gases from the environment. Various agencies have evolved to help businesses assess the efficacy of carbon credits including BeZero Carbon.

Stakeholders are increasingly considering the business as part of the broader ecosystem and are less inclined to absolve a business for 'sins of the connected.' A great example is that of 'scope 3' emissions where the consideration and disclosure by a business of not only its own directly generated GHG emissions but also those of its supply chain are crystallising in law and standards.

The concept of 'additionality' doesn't just apply in an environmental sense. Regulation such as the Nasdaq Board Diversity Rule has led to the imperative for Boards to consider, measure and do something about the diversity on their boards. The Nasdaq rule requires companies listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange to publicly disclose board-level diversity statistics as well as have, or explain why they don't have, at least two 'diverse directors'. In theory this should ultimately lead to increased representation for minority groups at senior leadership levels.

However, a report by Deloitte and the Alliance for Board Diversity in 2021 found that some Fortune 500 company boards were “recycling” board members to fulfil diversity quotas. Over one-third of board members of colour and two out of every five Black members held seats on more than one Fortune 500 board in 2020, according to the research.

Hiring from a limited pool not only reduces opportunities for others to enter board level roles, but it narrows the expertise and diversity of thought that these boards offer.

I have always felt that an organisation meets is diversity targets at the 'application' stage and not at the 'offer' stage. Encourage a diverse group of applicants to apply and then you can focus on the skill set and aptitude desired for the role or team being hired for. By empowering the broader group to consider an industry or organisation type or role as something they can apply their skills to, a business can improve mobility for the overall group and the quality of the talent pool available to their industry and themselves.

So again we can see that additionality requires us to look beyond the business in isolation.

Really the question that needs to be asked is whether "what I am doing is making the world as a whole a better place or not?"

Avoiding greenwashing in investment products

The UK Financial Conduct Authority as released proposals for regulations and guidance on greenwashing. One of the proposals is to introduce 'sustainability' labels for investment products (in section 4.21, page 30):

- Sustainable focus = investment in assets that are environmentally or socially sustainable.

- Sustainable improvers = investments in assets that can improve their environmental or social sustainability over time.

- Sustainable impact - solutions to social or environmental problems to achieve real-world impact.

Tom Gosling provides an excellent critique of the regulation believing that there is much to like, but also some questions and some things to work on. Among the areas that he welcomed was the fact that the FCA "did not impose any prohibitions in relation to stock-lending or use of derivatives, which could have had unintended consequences that are tangential to the objectives of the new regulation." Gosling does emphasise that some aspects may need some work.

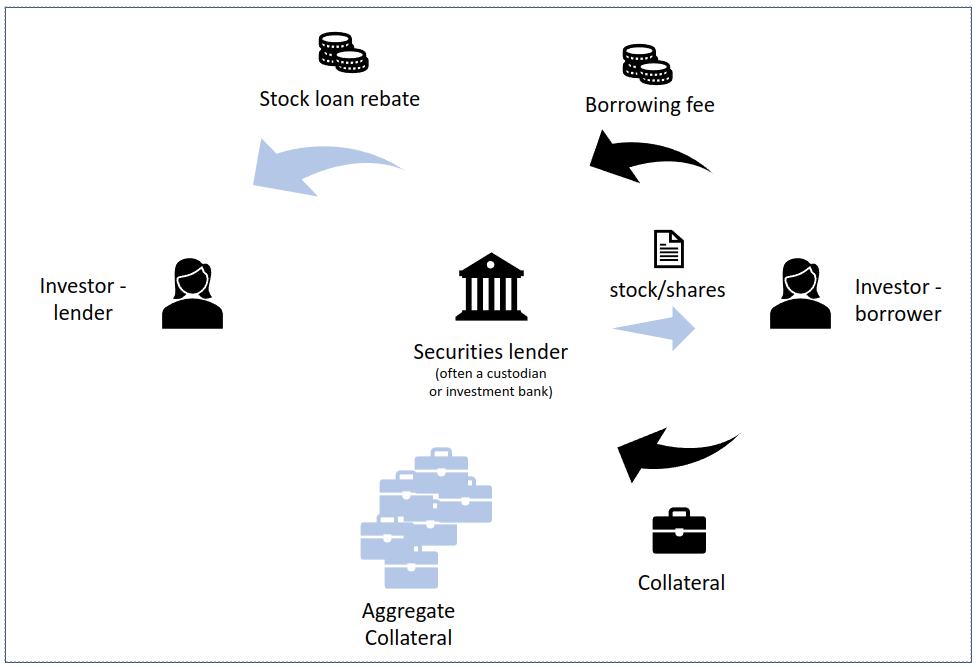

Stock lending is one area where inadvertent greenwashing is possible. Let's take a step back. What is stock lending? There will be occasions where a fund manager wishes to sell or have an underweight exposure to a listed business. That may be to provide a hedge against a long position that they have. For example, let's say they own shares in a company that sells cars and trucks, but they are worried about the trucks business, so they sell short (or just 'short') a pure play trucks company's shares. It could also be because they feel a share price could fall and they want to take advantage of that, but they don't own any of those shares.

In both cases one can borrow the shares they want to sell for a fee from someone who owns them through an intermediary (a securities lender) and then sell them in the open market. Like with most loans, some collateral needs to be provided as security so that if you are unable to pay back (or return the shares you borrowed) the lender has some compensation for the value. Below is an overview.

The issue I'm highlighting arises with the collateral. In practice, the investor-lender in this case receives aggregated collateral of more than the value of the shares they have lent out (in Europe it is typically 105%, but higher in the US, for example).

If a lender has lent out ESG or sustainability-related securities and has collateral that could contain low scoring ESG or 'unsustainable' securities is that lender greenwashing? It is not so straightforward as the lender would be entitled to the proceeds from selling that collateral as opposed to the collateral itself. A whole other article in itself.

Conclusion

As a broader group of stakeholder interests have come to the fore including employees, customers and the community at large there has been a shift in thinking from not just considering the impacts 'of' the environment, social and governance aspects and how they impact a business but also the impact of the business 'on' the environment and society as a whole. In other words, considering the business as part of a broader ecosystem.

With that in mind, if businesses understand how they fit into that ecosystem and the materiality and relevance of their actual and potential impact, they can be the most effective and avoid the traps of inadvertent greenwashing.

They can be genuinely additional, both in terms of return and the sustainability transition.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.