Thematic Thoughts: Financial risks from climate change

Rising sea levels are not just a threat to people. They also could create material financial risks, from what we call asset impairment. And given the long asset lives of most infrastructure, the risk is getting closer than you might think.

I don't normally write about the science of climate change. I am not an expert, and others write about this with a lot more authority than I can. However, decades of financial experience have taught me a lot about company risks and opportunities. And one increasingly key financial risk is too much water - from sea level rises and flooding.

For this blog I have put together two related pieces of climate related research that recently caught my eye. The first is the 2023 report from the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative. For those like me who were not familiar with the term, the Cryosphere is Earth’s frozen water in ice sheets, sea ice, permafrost, polar oceans, glaciers and snow. History tells us that when the world's cryosphere melts, the sea level rises.

And the second related piece of analysis is from CostMine Intelligence, looking at what percentage of global copper mines are at risk from flooding. Sea level rise and flooding are the same side of the climate change coin - linked by warmer temperatures.

As a banker turned investor, I used to spend a lot of time thinking about financial risk and opportunity. Specifically where the financial markets seemed to be mispricing risk. Or putting it another way, where they are 'looking the wrong way'. Sea level rises and floods seem to be such a risk.

I appreciate that for many people (especially the wealthy) and for some companies, just moving away is a viable option. But for most people and companies, moving is not practical. Could this mean that a decent percentage of our infrastructure could be worth a lot less in the future, or maybe even nothing. What we call in my industry asset impairment.

This is a What Caught Our Eye story - highlighting reports, research and commentary at the interface of finance and sustainability. Things we think you should be reading, and pointing out the less obvious implications. All from a finance perspective.

It's free to become a member ... just click on the link at the bottom of this blog or the subscribe button. Members get a summary of our weekly posts, including What Caught Our Eye and Sunday Brunch, delivered straight to your inbox. Never miss another blog post !

Sea level rises - we cannot negotiate with the melting point of ice.

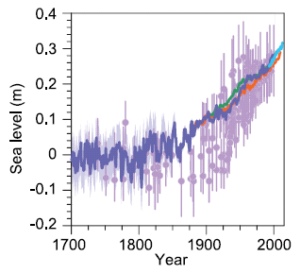

Let's start with the big picture. Sea level. I trained as an engineering geologist, and long term sea levels changes are important in understanding current rock formations. We know that the sea level rises (and falls). What we don't often appreciate is how much it rises. To quote the CSIRO "sea levels typically vary by over 100 metres during glacial-interglacial cycles". And the sea level has increased by more than 120m since the end of the last ice age.

And it's still increasing. I am sure you have seen the analysis that it's currently rising at about 3-4mm pa. Now that might not sound much to you. But it adds up. The current sea level is c. 240mm higher than in 1880.

But that is only part of the picture. As the report sets out, the simple physical reality of the melting point of ice means that a 2°C warmer world will result in extensive, potentially rapid, irreversible sea-level rise from Earth’s ice sheets.

And what does an 'extensive' sea level rise mean? At 2°C warmer, it's between 12m and 20m.

Why does this matter to a financial person? Earthdata sets out estimates from the United Nations that 40% of the world's population lives within 100 km of a coast, meaning that close to three billion people could be impacted by changes in sea level. And coastal communities are centers of economic, social, and cultural development.

Earthdata estimate that global sea level is projected to rise another 1 to 8 feet by 2100. If that happens, then many of our large coastal cities (Shanghai, New York, Miami and Dhaka) will either be flooded, or they will have to spend vast amounts of capital on flood prevention. That will not only impact people's houses, office buildings and factories. It could also inundate much of our physical infrastructure. So power stations (where water is used for cooling), water and sewerage treatment plants, chemical plants, roads, railways and airports. Plus obviously ports.

These are what we describe as long life assets. They should continue to be productive for a long time. Europe renovates around 1% of it's building infrastructure every year. One way to think about this is the typical new building will still be there in around 100 years. Power stations and water treatment plants should last more than 40 -50 years. And railways and roads have useful lives that are longer still.

My point is that when we work out the financial case for much of our infrastructure, we assume it's going to have an economically useful life that extends well out into the second half of this century. Unless of course sea level rises change this.

The Indonesian government estimates that the cost of building a replacement for Jakarta (which is rapidly sinking) will be c. US$32bn. And knowing what we do about government estimates, we can be sure it will turn out to be more expensive.

Taking a US example, the World Economic Forum highlights that almost 1,100 critical buildings in coastal communities could be at risk of monthly flooding by 2050. And some communities could become un-liveable within two to three decades.

If we are involved, directly or indirectly, in financing infrastructure and/or housing in coastal regions of the world, we need to be thinking about this. And we should not assume that insurance will fix the problem for us.

Plus, we cannot hide behind the 'fact' that our debt will be repaid long before then. That ignores refinancing risk (a topic for another day).

One last thought

It's not just rising sea levels that create financial risk. Flooding, from more intense rainfall, is also a risk we need to watch. CostMine Intelligence, have looked at what percentage of global copper mines are at risk from flooding. In their recent report they estimate that "some 19% of the world’s copper projects fall within the two highest risk categories of our Extreme Precipitation Index, which measures the frequency and intensity of heavy rains in the current climate. However, that number could rise to 25% by mid-century." Sites in major copper producing countries like Canada, Australia and the DR Congo will likely be among the most exposed.

If we are to deliver the sustainable transitions, we are going to need a lot more copper. And we know that it takes time, sometimes a long time, to get a new mine up and running. So losing mining capacity to flooding would not be helpful.

Please read: important legal stuff.