Energy, methane and orphaned wells

Abandoned and stranded fossil fuel assets need to be considered.

Summary: US Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland issued a Secretary's Order to establish an Orphaned Wells Program Office to ensure effective, accountable and efficient implementation of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. It includes a US$4.7 billion investment to plug orphaned wells.

Why this is important: Methane is a powerful Greenhouse gas and accounts for approximately 20% of global emissions. It is more potent than CO2 at trapping heat, the quantum of which depends on the time horizon that one is looking at. Over a 100 year period (the Paris rulebook timeframe) methane is 29x more potent; over a 20 year time period it is 82x more potent given the shorter lifespan of methane in the atmosphere. So, reducing methane emissions is a big deal.

The big theme: If we are to reduce O&G usage, there will be a whole series of costs we as a society may need to face. Some are to do with compensation for stranded assets (an unpopular topic) and some are to do with cleaning up the existing infrastructure. This is a theme that could get material and run for many decades.

The details

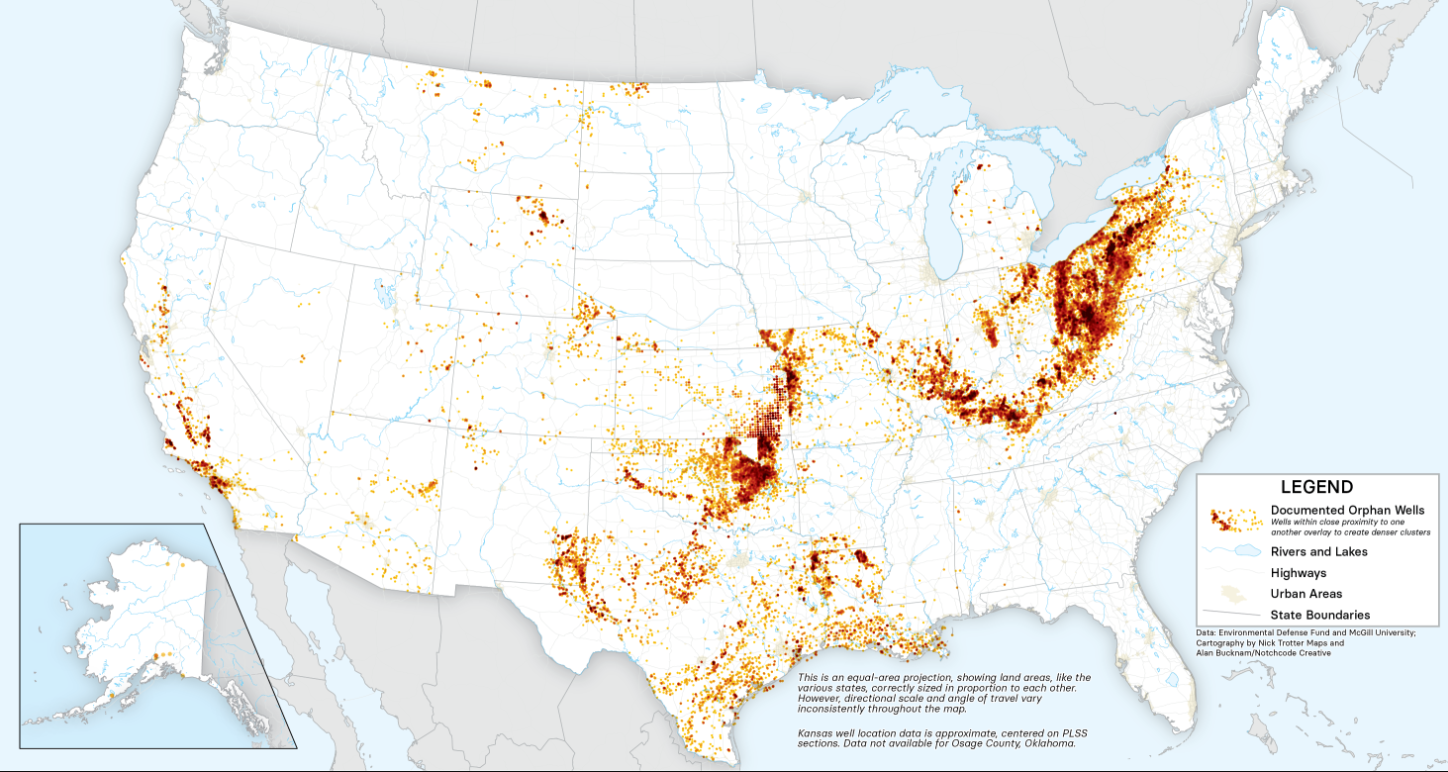

Los Alamos National Laboratory in the US is leading a consortium to find abandoned orphaned oil and natural gas wells. Orphaned wells are wells that were never documented on public records and essentially abandoned by their legal owners. Information about ownership and construction has been lost, as has responsibility for methane emissions. The goal of the consortium is to then prioritize these wells for plugging and remediation.

The bipartisan Infrastructure Bill provides US$30m funding through the US Department of Energy, Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management for this work. There is a five-year time horizon for establishing a framework, developing and testing new technologies, and ultimately deploying those in the field. It is expected that the consortium will rely on drones, lightweight sensors, geophysical techniques and Machine Learning. A workshop to kick things off took place in April 2022.

Texas has been awarded an initial grant of US$25 million from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law which it plans to use to plug 800 higher risk documented wells. However, there have been some issues. The state is refusing to fix certain orphaned wells. The Texas Railroad Commission would normally take responsibility for cleaning up orphaned oil and gas wells. However, where unproductive wells were previously transferred as water wells (“P-13 wells”) the Commission argues that they are not oil & gas wells and therefore not their responsibility. According to the Commission there are as many as 2,000 documented P-13 wells.

Why this is important

Methane is a powerful Greenhouse gas (GHG) and accounts for approximately 20% of global emissions. However, it is more potent than CO2 at trapping heat, the quantum of which depends on the time horizon that one is looking at. For example, under the IPCC’s 6th Assessment report assumptions, over a 100 year period (the Paris rulebook timeframe) methane is 29x more potent; over a 20 year time period it is 82x more potent given the shorter lifespan of methane in the atmosphere. So, reducing methane emissions is a big deal.

More than 100 countries (70% of the global economy) have adopted the Global Methane Pledge which is a commitment to a collective goal to reduce global methane emissions by at least 30% from 2020 levels by 2030. That should reduce warming by at least 0.2 degrees C by 2050. The biggest single source of methane emissions are wetlands (specifically freshwater wetlands - note that tidal wetlands actually continually accumulate carbon over their lifetimes and do not release methane) - with the biggest source of anthropogenic methane coming from agriculture. However, combined methane emissions from the energy sector, waste and biomass burning together exceed that.

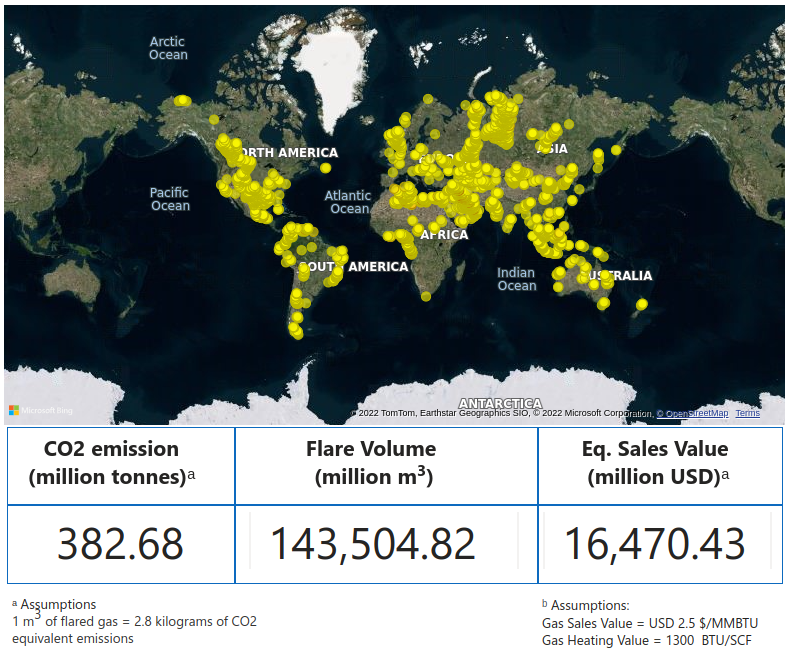

What other issues does this raise you need to be aware of? There are two main sources of methane from the oil and gas industry. The first is flaring, the burning of excess natural gas that comes from the oil extraction process to prevent pressure build up. The World Bank tracks routine gas flaring globally and estimates that in 2021 almost 144 billion cubic metres of gas was burned through flaring with over 380 million tons of CO2 equivalent emissions. Just for 2021.

Solutions include re-injecting the gas into the reservoir, collecting and transporting it through a gas pipeline, or indeed reducing the amount of production. These are solutions that are worth investing in.

The other source is leakage. This can be from poorly maintained infrastructure either at platforms and wells, storage facilities or pipelines. Two examples of “super-emitter” events are one from a storage facility in Los Angeles in 2015 (almost 100,000 tonnes) and another from a platform in the Gulf of Mexico in December 2021 (40,000 tonnes). In fact, they were only caught by a European Space Agency satellite. The UN Environment Programme launched the International Methane Emissions Observatory in October 2021, recording oil & gas industry emissions.

Back to the orphaned wells. Given that many will have changed ownership many times before being abandoned, the likelihood that they are in disrepair is high and hence potentially an important source of leakage. Given methane’s near term advanced warming potential, the benefits of prioritising and plugging are clear. One question is - who pays? If it’s the government there is the obvious moral hazard issue, and also the time scale for action. But it’s also worth asking if we can find financial incentives to get the private sector to accelerate the process.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.