Electric trucks - the future of freight?

While it might appear from recent news stories that the debate about what will power the trucks/HGV’s of the future is ongoing, in reality it's actually pretty much already decided. Short of any surprises in the next couple of years, it's going to be electricity.

Summary: While it might appear from recent news stories that the debate about what will power the trucks/HGV’s of the future is ongoing, in reality it's actually pretty much already decided. Short of any surprises in the next couple of years, it's going to be electricity. There is still an ongoing discussion about battery charging vs overhead power, but the notion that we will be using hydrogen or biofuels at any scale is fading, and fading fast. But the process has really only just started, and we have some tough decisions ahead of us.

Why this is important: Decarbonising transport, especially heavy transport, is partly about GHG emissions, but it's also about reducing air pollution - while at the same sustaining the freight transport sector. At present pretty much everything we consume spends at least some time in a (currently) diesel truck/HGV. Our freight infrastructure is essential to our economy. We need to be realistic. This is not going to be an easy or low cost transition. Issues include what charging infrastructure do we need, the capacity of our electricity grid, who pays for any overhead power lines, and of course financial support for early adopters.

The big theme: According to Our World in Data, Transport accounts for 24% of energy related emissions and 16% of total emissions, of which nearly half (45%) is from passenger transport. The Transition in Transport is one of the most advanced, especially for passenger cars, but as the industry moves up the innovation S curve, there will be numerous new challenges.

The Detail

Summary of a study published in electrek

- On April 28, the California Air Resources Board unanimously approved new rules that mean that from 2036 manufacturers must stop selling non compliant trucks, and that fleet operators must progressively move to zero emission (ZEV) fleets . Fleet operators can phase their transition, with the largest trucks (sleeper cabs etc) only having to be zero emission beyond 2042. However, some operators, such as state and local entities, have earlier targets (purchasing 50% ZEV by 2024 and 100% by 2027).

- Part of that plan involves the use of more alternative fuels, but mostly it comes down to transitioning away from diesel engines to vehicles powered by electric motors. Many people are displeased with the new rules. The California Trucking Association suggests that not only are the rules likely to fail, they will also “ cause chaos and dysfunction”.

Why this is important

- The necessary transition of our heavy transport system to a decarbonised future is going to be complex and messy. In thinking about this it's important to recognise that heavy transport actually covers a wide range of sub sectors - everything from the (larger) delivery vans we see around our cities, through buses, all the way up to the massive articulated truck and trailer units that roll up and down our highways. And each sub segment has different challenges and needs. Some transitions will be easier - delivery vans and buses are an obvious example, as they return to depots on a regular basis.. And some will be really tough, with the largest HGV’s being the toughest.

- So, we shouldn't think about this challenge as just having one solution. And similarly, we shouldn’t assume that the challenges faced in the electrification of large articulated HGV have much in common with electrifying the local Fedex delivery fleet ! One obvious challenge is EV charging infrastructure, a topic we discussed in a recent blog on charging for buses and trucks. Another is the ability of the electricity grid to cope with the large “point” loads involved in changing HGV’s, although to be fair, this is part of the wider challenge of preparing our grids for a decarbonised supply and demand future.

- And then we have financial support. Yes, for some heavy transport vehicles the whole life economics already look positive, but not for all. A recent US study by Burke, Miller, Sinha & Fulton, looked at the maths of the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO). For commercial vehicles this is the most relevant metric, more important than the cost to buy, as it includes the cost to operate. This allows truck owners to model the financial implications of switching to electric fleets.

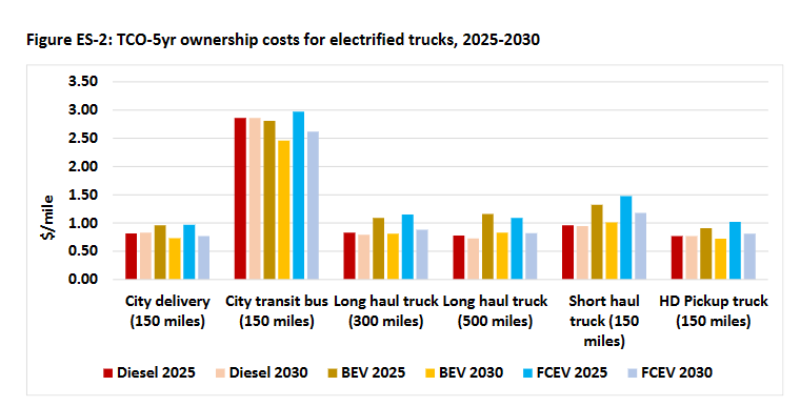

- What does the study show? To simplify, by 2025 “battery electric vehicles are cheaper than fuel cells, and they are close to being competitive across truck types. By 2030, the battery electric trucks will be even cheaper, with a lower TCO in city usage and only slightly higher for long distance usage. Fuel cell vehicles have higher TCO than the comparable battery electric vehicles, but in most cases they are close to that of the diesel vehicles”. In the spirit of a picture is worth a 1,000 words ..... Note that this analysis suggests that Battery Electric Vehicles (BEV) will become the cheapest alternative on a TCO basis by 2030, but not in all use cases.

- So, we have the beginnings of an answer, but we still have some work to do. Given this complexity and the cost of the transition, why should we go to all of this effort? Its simple - even ignoring the GHG emissions issues, CARB says its Advanced Clean Fleets rule will promote $26.6 billion in health savings from reduced asthma attacks, emergency room visits, and respiratory illnesses, and that fleet owners will save an estimated $48 billion in their total operating costs from the transition through 2050. And on GHG emissions, while trucks represent only 6% of the vehicles on California’s roads, they account for over 35% of the state’s transportation-generated nitrogen oxide emissions and a quarter of the state’s on-road greenhouse gas emissions.

- So, given that the benefits (lower GHG emissions and less air pollution) go to the wider society, we should expect governments to assist, either through financial aid or regulation. This obviously raises a whole stack of questions - how much financial aid (and how much can be stick over carrot ie regulation over subsidies), how quickly can we produce enough trucks at the right price, and what do we do about long distance/long haul trucks (where the research above suggest they will likely still have a higher TCO by 2030 ?). Maybe the answer is an overhead electrified system on our main routes, which we explored in a recent blog.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.