Easing the perceived pain of retrofitting payback

The simple payback period calculation for retrofitting (amount spent / annual savings) misses nuance

Summary: Retrofitting can improve the operational efficiency and emissions profile of existing buildings and infrastructure. However, the approach to funding and implementation will depend on the kind of infrastructure, the owner / user and the location. The most common source of resistance to retrofitting and upgrading is the perceived long payback period for the investment made. That is particularly acute where it is an individual homeowner or individual commercial property owner. The simple calculation of 'amount spent to complete the upgrade/retrofit' divided by the annual savings may be too simplistic and miss nuance that can bring that payback period down - and this can greatly impact the decision to proceed. For some householders, however, the payback period could still be too long or they simply don't have the means to fund the initial outlay. This is where place-based investment comes in.

Why this is important: Communities are important stakeholders for almost every business. As a sustainability professional, understanding the nuances of decision making for individuals and businesses can be helpful in designing appropriate strategies.

The big theme: The built environment, encompassing residential and commercial buildings, communal areas such as parks, and supporting infrastructure such as energy networks, mobility, and water supply, is an important sustainability theme. It is an integral part of societal existence and a major resource consumption problem (40% of global raw materials) and decarbonisation problem (as much as 40% of energy-related GHG emissions) that needs investor, government, business and consumer attention.

The details

Why retrofit?

The built environment is a key focus area for decarbonisation. It is one of the biggest sources of energy-related carbon emissions (~40%)

Making homes and commercial property more energy efficient can help with both affordability and more energy secure in addition to reducing incremental greenhouse gas emissions.

Restating the law of conservation of energy: Generation = Consumption; or in other words the energy generated upstream is consumed downstream in the built environment.

If we can lower consumption, then we can lower generation which in turn should lower harmful emissions (even before we talk about the mode of power generation).

Furthermore, we can subdivide Consumption: Consumption = Usage + Wastage; or in other words what we use usefully and what is lost to the universe (or used up 'un-usefully').

Usage and Wastage can both be lowered through improvements in efficiency which can be both active and passive, and through behavioural changes (for example, resetting what we assume to be a comfortable temperature).

When designing and building new properties and infrastructure there is much that can be done to improve both the embedded carbon footprint, which is created when taking raw materials and turning them into buildings, and operational carbon footprint (created through the running and operating of the building.

But what about existing buildings?

We previously discussed a number of ways in which existing structures can be repurposed when they reach the end of their useful operational life or even while they are still operational, their overall efficiency can be improved. This can involve retrofitting more modern, low carbon, energy efficient technologies and features or even reusing materials and elements from existing structures that have themselves come to the end of their lives.

You can read that Deep Dive here 👇🏾

For an individual homeowner, for an upfront investment, they could save money on their energy bills every year, so why don't more homeowners jump at the chance?

Jon Fletcher, founder of big clean switch, a market-leading employee energy benefits provider, illustrated the problem in a LinkedIn post with an example from a home they recently completed an energy assessment on.

An Energy Performance Certificate or EPC tells you how energy efficient a building is rating from A (very efficient) to G (inefficient) and this particular home's most recent EPC from 2022 highlighted that to move from a D to a B rating the homeowners/occupiers would need to spend up to £30,150. Most if not all of that would likely be upfront. The first problem then is how would one fund that upfront cost?

The second problem, which is really the focus of this blog, is if that spending generates savings, how long does it take to break-even? This is the payback period.

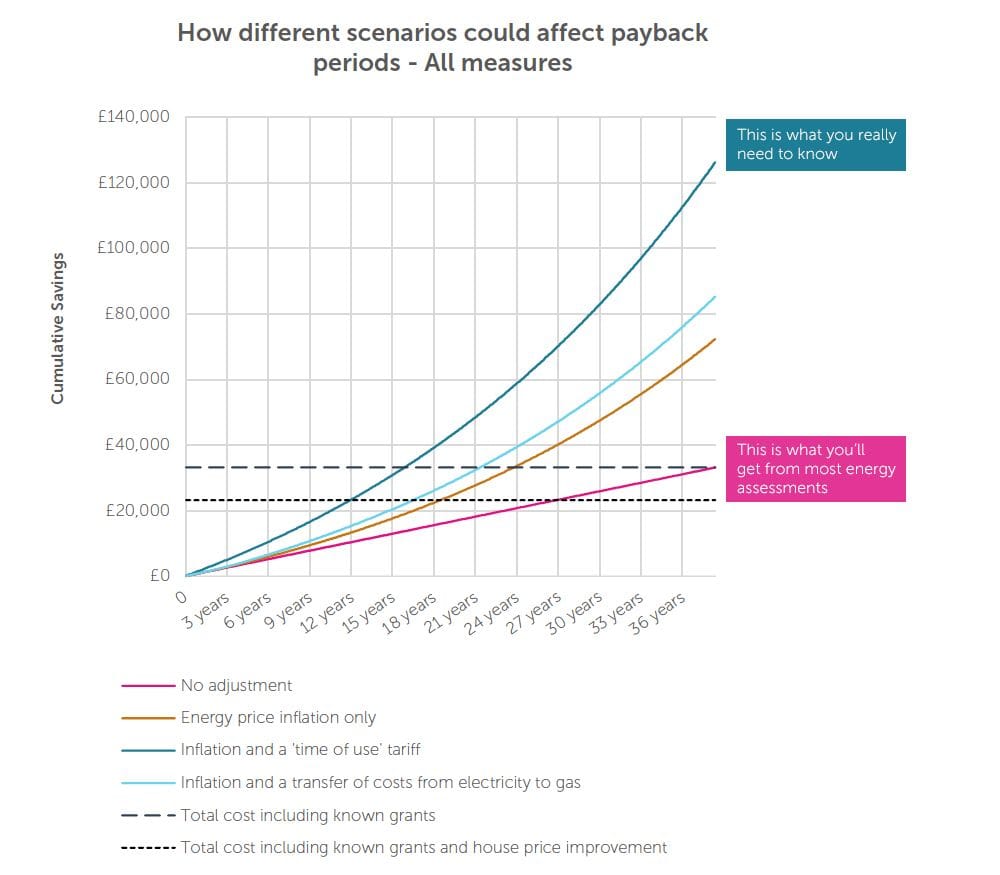

In the example from Jon, the EPC gave the savings from up all of the individual measures as £704 per year.

A simple payback period calculation, dividing the upfront cost of approximately £30,000 by annual savings of approximately £700 gives a payback period of almost 43 years.

43 years?! That is problematic when, in the UK for example, the average homeowner occupier is in their fifties! So you can see how there can be resistance to making that investment.

However, the actual payback period may be significantly shorter than the simple calculation above suggests...

Is simple payback far too pessimistic?

In his LinkedIn post, Jon focused on two key areas that impact that simplistic payback calculation in the real world:

- The price of energy

The price of energy isn't going to remain the same over that 43 year period. There is likely to be inflation, not least of which due to large investments that will be needed to improve our grid infrastructure. Another aspect is the cost of electricity which could potentially come down relative to gas making the annual savings number higher.

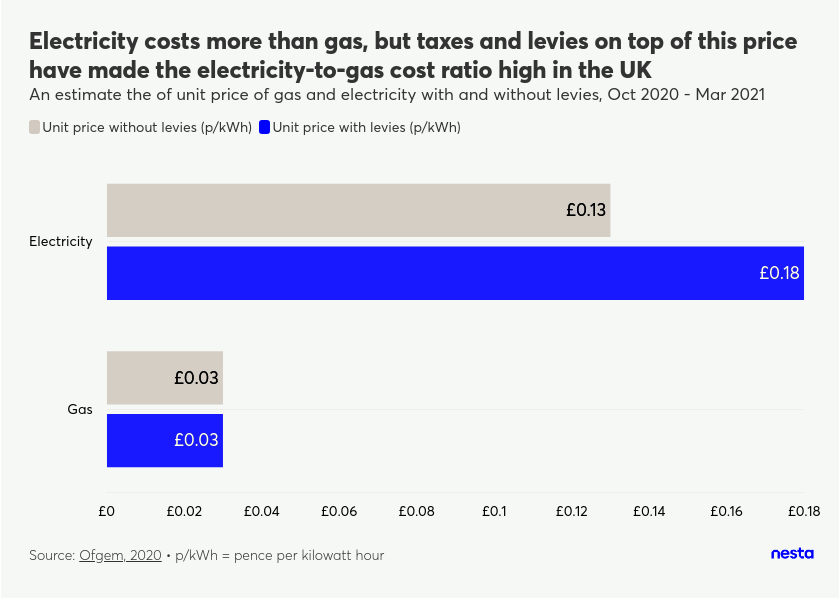

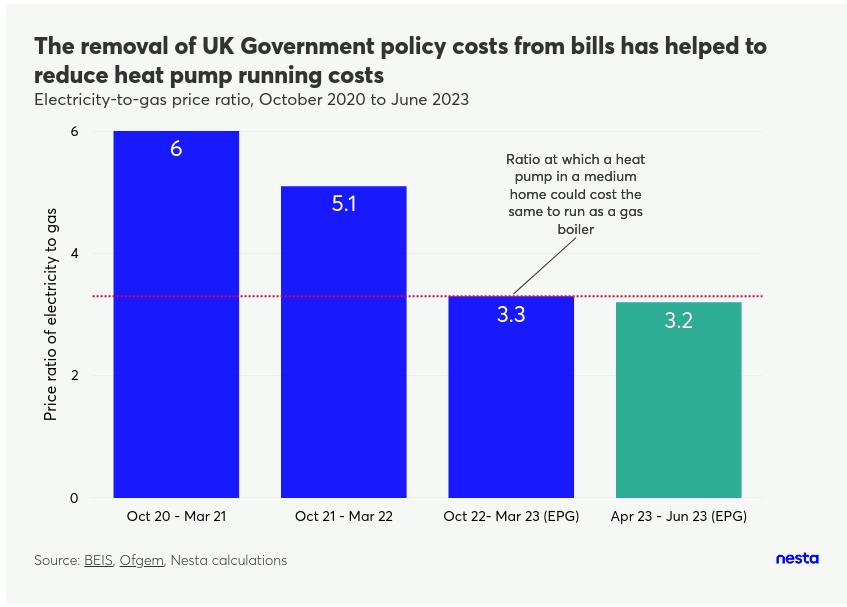

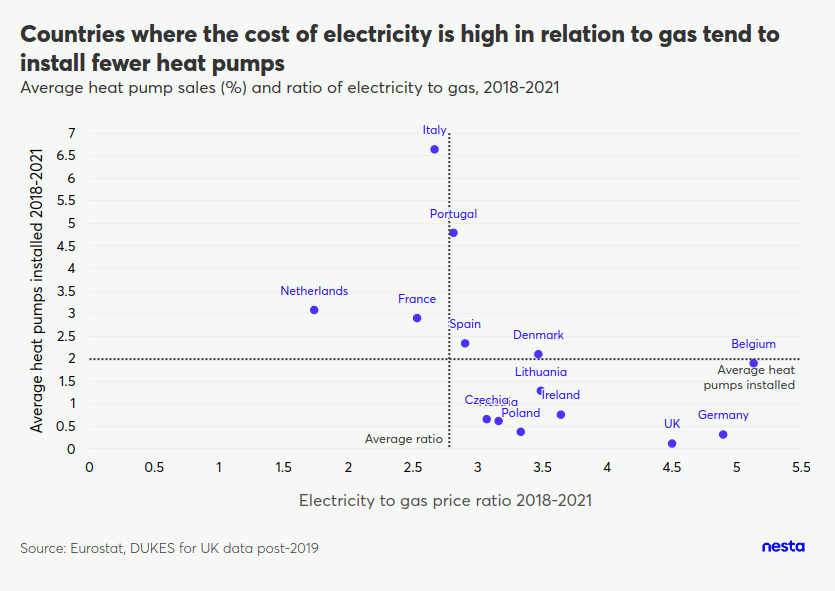

A recent report from the Heat Pump Association highlighted that "... Great Britain [has] one of the highest electricity to gas price ratios (3.97) in all of Europe."

They go further to point out that on average across Europe, "for every increase to the price ratio of 1, the sales per 1,000 households decrease by 6.4."

Nesta has some interesting charts illustrating these points:

- Time of use tariffs.

Anyone living in the UK will be familiar with British Gas's PeakSave Sunday schele offering half price electricity for consumers between 11am and 4pm on Sunday's with the aim of getting people to spread their consumption from peak periods to off-peak periods.

Some providers also have different tariffs - Jon highlights OVO's dedicated heat pump tariff and Octopus Energy's time of use tariff, Intelligent Octopus Go. Consuming during the applicable times further lowers the actual price paid and hence the relative annual savings.

EPCs have not historically accounted for these time of use tariffs in part because of the relatively recent emergence of app-based controls that can automatically divert consumption and battery storage which is key to optimising homes to use off-peak power.

In addition to the above two factors, there is also the potential for house price improvements from being more energy efficient which can also lower the payback period hurdle, albeit that may not be realised until one sells one's house.

In the home example that Jon presents the payback periods under different scenarios taking into account the above, range from the 43 years in the simple calculation down to 12 years.

The decision to retrofit becomes more appealing.

For some the payback can still be a barrier

This section of the blog is written by Rufus Grantham, co-founder of Living Places.

Living Places is a specialist not-for-profit organisation with diverse expertise that designs and advises on the implementation and funding for the place-based approach.

They believe the net zero transition can be delivered at pace, will make people better off, and will create healthy and resilient neighbourhoods across the whole country.

They do this by bringing together communities, local and national government, business, institutional fund managers and charities to collaborate on whole neighbourhood scale projects. We introduced the concept here 👇🏾

Over to Rufus...

I wholeheartedly support the analysis from Jon. The payback periods for retrofitting often quoted can paint an overly pessimistic picture from which to base a decision. In the scenarios for the example Jon presented, a 12 year payback period is certainly better than the 43 years of the simplistic calculation but still may prove too much of a barrier for segments of the population.

Three further points I would make in considering the payback period and ultimately the ability or incentive for a homeowner to go ahead with a retrofit:

- Time value of money: If I pay out £30,000 today, I will want to receive more than £30,000 back over a decade or two to maintain my purchasing power as prices generally inflate, not to mention the opportunity cost of an investment return on that capital that I have locked up (or borrowing costs to raise it if I don't have a spare £30,000 hanging around). This will shift the hurdle up slightly and weigh, at the margin, on the payback period.

- House Price Uplift: It is true that there is some emerging evidence that more energy efficient homes can command a higher price. However, if we move to scaled retrofit, the scarcity value of a better EPC will drop away. In addition, with a cost of housing crisis in the UK for both purchasing and renting, a new large collective cost liability may actually weigh on valuation.

- Maintenance and Replacement Costs: For the analysis to hold we have to assume that the energy savings are maintained in the very long term to cover the payback period. In order to achieve this there will need to be money spent on maintaining the assets that deliver the saving and replacing them when they reach end of life. Solar panels, batteries, invertors, heat pumps etc will all have an operating life and part of the energy saving will need to be diverted to replace some during the payback period which in turn will extend the payback period. Whilst the maintenance costs for retrofits may be lower than existing gas boilers and infrastructure for example, we have already factored out that legacy cost.

Even taking the above points into consideration, the net effect of all this is still that the overall conclusion is right; that simple paybacks are probably too negative and in reality they may be much shorter. However, that doesn't get around the fact that for most people, during a cost of living crisis, investing tens of thousands into retrofit through additional borrowing is deeply unappealing psychologically, whatever the financial analysis says, and for many simply not an option.

Repayment over ten to twenty years is clearly better than over forty but still, I would argue, longer than most individual's comfortable investment period. This all helps to incentivise a motivated (and wealthier) early adopter market which is important, but doesn't feel like a mass solution.

Key considerations for individual residents are cost (which we have mainly discussed in this blog) and disruption. If the technology, planning and contracting decisions are taken off their hands and the disruption to their lives is minimised, a resident can focus on affordably living in their homes at an appropriate comfort level.

That brings me back to place-based models.

Thank you Rufus... back to The Sustainable Investor

Conclusion

The built environment is an integral part of societal existence and an important sustainability theme. As well as forward looking new construction and design, there are solutions to improve existing stock, through retrofitting. However, affected individuals need to clearly understand all of the dynamics involved before they can make a decision to retrofit. Organisations such as big clean switch can help individuals and employees of businesses get better informed and help make changes, from switching energy providers and tariffs to help with insulation, to improve the efficiency of their homes.

For many, the upfront costs and disruption involved are too much of a barrier. That is where a place-based model comes into play and the resident can focus on affordably keeping their home at an appropriate comfort level with the secondary benefit that harmful emissions are also being reduced.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.