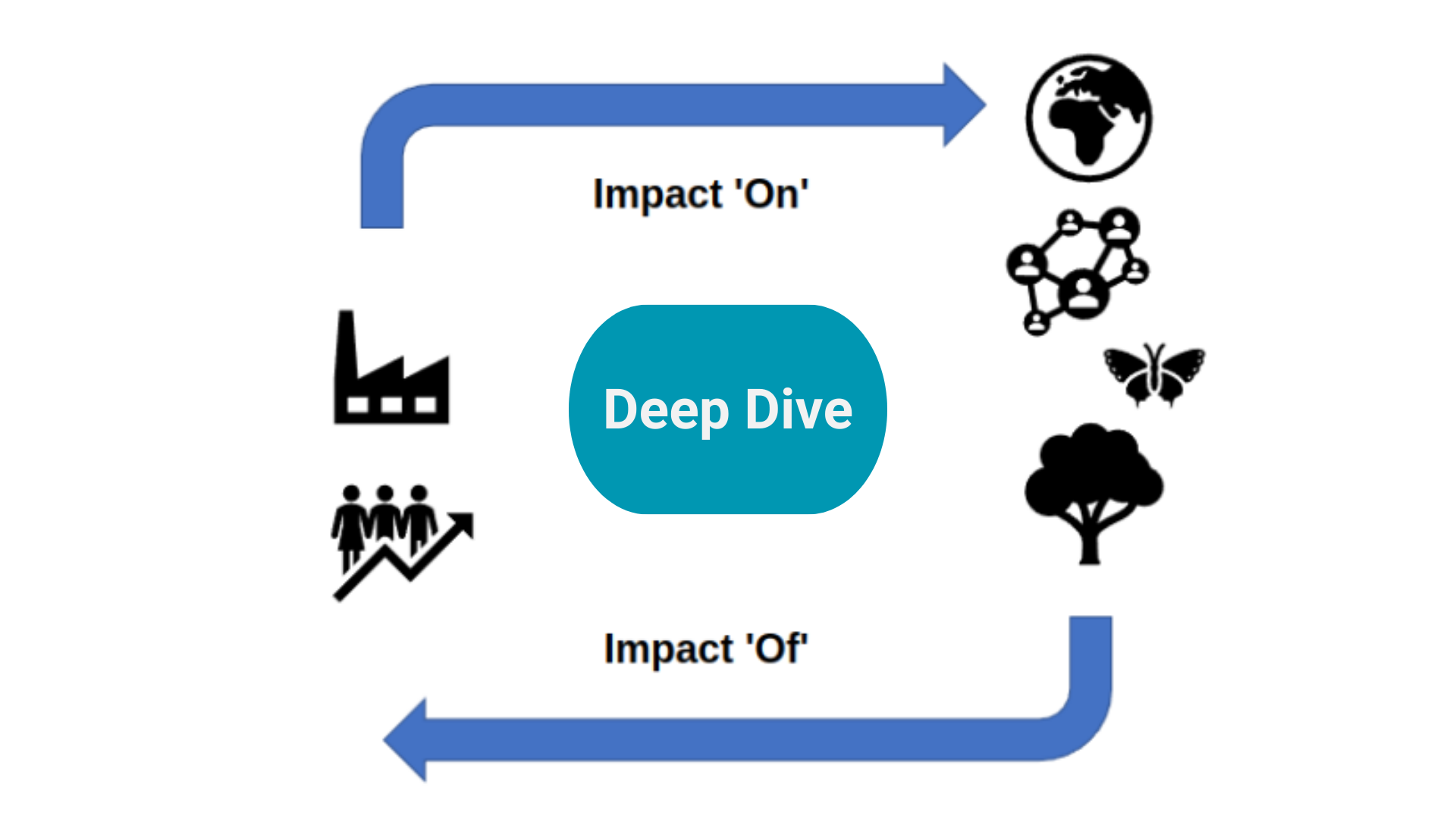

Double materiality - the 'on' and 'of' switch

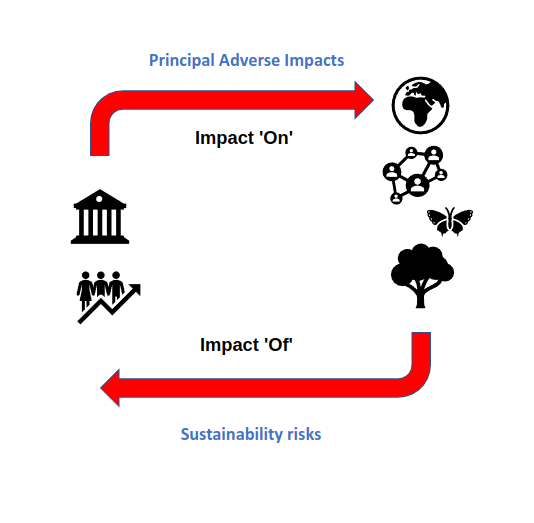

There has been a shift in thinking from just considering the impacts 'of' the environment and society and how they impact a business to also considering the impact of the business 'on' the environment and society as a whole.

Summary: There has been a shift in thinking from just considering the impacts 'OF' the environment and society and how they impact a business, to also considering the impact of the business 'ON' the environment and society as a whole. A complete circle. What that new thinking is really saying is we need to start thinking about organisations and businesses as part of a broader ecosystem that includes people and planet. We also take a look at Biogen and The HEINEKEN Company as examples of companies that have taken on board relevance and double materiality in their sustainability initiatives that should also help to provide security to their longer term business futures.

Why this is important: Increasingly disclosure standards and requirements will embody the concept of double materiality. Hand-in-hand with materiality is the concept of relevance. For something to be material it has to matter to the business and its stakeholders. It has to be relevant. The danger of taking a broad brush approach to sustainability to meet an aggregate score is that a business inadvertently greenwashes.

The big theme: Rather than 'Enterprise Value' we should be thinking about the bigger picture, the whole pie. As Professor Alex Edmans espouses in his seminal book 'Grow the Pie', the primary goal of a company should be to serve society rather than generate profits. This approach "enables investments to be made that end up delivering substantial, long-term pay-offs." It's not to say that profits don't matter, its more that by focusing on meeting the wider needs of society, profits are a result, not an objective. In other words it is not just worthy, it is good business. Thinking about that bigger picture is good business.

The details

Materiality - an investor's perspective

In August 1994 I started a training contract at Price Waterhouse, then one of the 'Big Six' accountancy and professional services firms that would later become one of the 'Big Four' as PwC. As an engineering graduate I had to complete a conversion course to be able to study for the professional accountancy exams en route to becoming a Chartered Accountant. One of the first things we learnt was the four fundamental accounting concepts: Going Concern, Consistency, Prudence and Accruals (also known as matching).

Wind the clock forward almost 30 years and my focus on sustainability, that first concept of 'Going Concern' seems highly appropriate! That's for another blog.

In addition to the four fundamental accounting concepts there were further general accounting concepts, one of which was materiality or the question of whether something matters. When it comes to disclosure and reporting what do we mean by materiality?

'Primary users' here are defined as an "entity's existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors"

Historically there has been an Enterprise Value (EV) approach, that one could describe as a unidirectional materiality view: what are the risks 'of' X to the business? Can the business manage these material risks and opportunities?

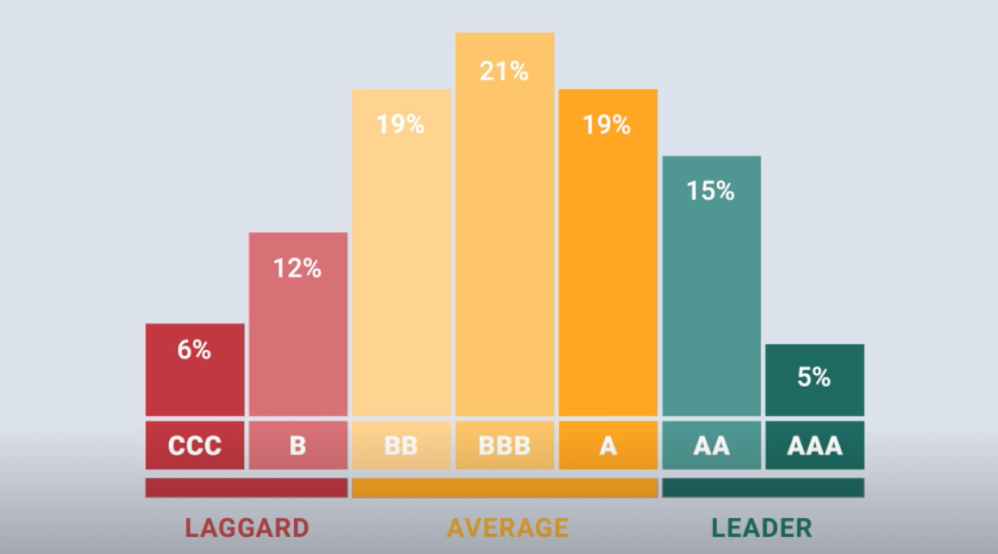

Even as the world has become increasingly aware of the significance of environmental and social factors and the governance required to manage those risks, ESG investing emerged with, in effect, that same EV approach, relying on data and scoring to assess how exposed a company is to ESG risks.

However, with that increasing awareness, a broader group of stakeholder interests have come to the fore including employees, customers and the community at large.

There has also been a shift in thinking from considering just the impacts 'of' the environment, social and governance aspects and how they impact a business, to also considering the impact of the business 'on' the environment and society as a whole.

What that new thinking is really saying is we need to start thinking about organisations and businesses as part of a broader ecosystem that includes people and planet. Rather than 'EV' we should be thinking about the bigger picture, the whole pie. As Professor Alex Edmans espouses in his seminal book 'Grow the Pie', the primary goal of a company should be to serve society rather than generate profits. This approach "enables investments to be made that end up delivering substantial, long-term pay-offs." It's not to say that profits don't matter, its more that by focusing on meeting the wider needs of society, profits are a result, not an objective. In other words it is not just worthy, it is good business. Thinking about that bigger picture is good business.

Hand-in-hand with materiality is the concept of relevance. For something to be material it has to matter to the business and its stakeholders. It has to be relevant. The danger of taking a broad brush approach to sustainability to meet a score (which can be implied with a singular focus on ESG metrics and scoring) is that a business inadvertently greenwashes.

Finally, we shall take a look at a couple of case studies of companies that have taken on board relevance and double materiality in their sustainability initiatives that should also help to provide security to their longer term business future.

Material vs. Immaterial Information

Let's start off by looking at what we mean by 'materiality'. The IASB definition considers the influence on decision makers. That suggests that something 'material' is important or it 'matters'. But how do I know if it matters and to whom?

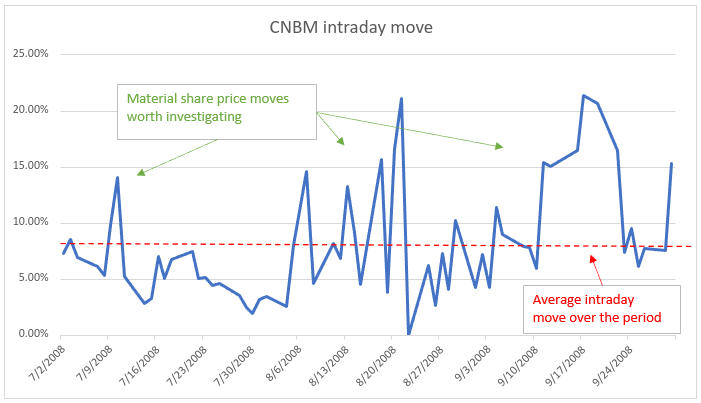

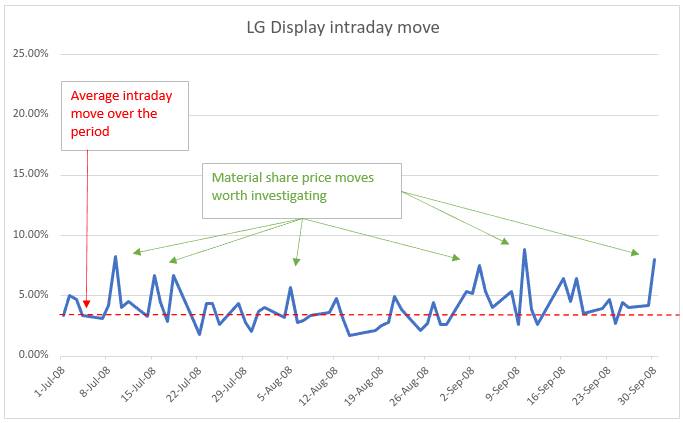

For a business, size and scope will come into play. For example, a £5 difference in the price of an item would be material if that item cost £50; it is probably immaterial if that item cost £10,000. In 2008 when I was Head of Content Development for Morgan Stanley in Asia, I was tasked with monetising the insights and ideas generated by colleagues both in Research and on the various sales and trading desks. Our clients who were asset managers and asset owners, valued our expertise and were happy to pay for that. The trick was delivering that expertise at the right time. One key way was to be out quickly with insightful commentary on unexpected moves in the market and be coordinated across teams to be able to also deliver the trading or other solutions needed by our clients. I led a team to build an alerting system that would nudge the relevant analyst, specialist salesperson, stock trader and derivatives trader when a share had an unusual price movement to investigate, conclude and communicate to our clients. What constituted 'unusual'? The lazy approach had been +/- 5%. That was problematic and not fit for purpose.

For example, China National Building Materials, a Chinese cement company had an average daily movement low-to-high of around 8% at that time. So when the stock moved more than that up or down, the system triggered everyone into action. However, LG Display, a Korean flat panel display manufacturer, had an average daily movement of around 4%. Therefore the trigger would occur at a much lower movement. By focusing on material movements we were able to avoid being just noise and our clients knew that when we did comment it was worth listening to.

(Data: Yahoo! Finance; The Sustainable Investor)

From a disclosure and reporting perspective, material items can be financial or non-financial. In the latter case, relevance is also important. For example, if a senior executive at a company were to fall ill and be unable to complete their duties, that could be considered material to the decision making process of a primary user such as an existing or potential investor. Indeed, when Steve Jobs announced his medical leave from Apple in 2011, the share price dropped 5.5% when markets reopened (in previous weeks, the daily movement was typically less than one percentage point), suggesting that those primary users did consider the information to be very relevant and material.

So size, scope and relevance are important in determining materiality. A point worth making here is that investors are already used to taking account of non-financial factors. Brand values, intangibles, and management competency have always been material, even when we might have struggled to put a financial value against them. So, it's not a new concept, it's just now being applied in a different way.

Is Climate risk (and are other sustainability risks) material?

In mid-2017, the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) published recommendations to encourage financial institutions and non-financial companies to disclose information on climate-related risks and opportunities. Their report had highlighted that "climate-related risk is a non-diversifiable risk that affects nearly all industries."

So arguably, climate-related risk is de facto material and hence the need for increased disclosure. Climate change is one of a number of sustainability-linked macro risks that investors, be they asset managers, asset owners or C suite executives making strategic decisions should be on top of to be able to adequately price or value investments.

Companies have been increasingly embracing the recommendations even though they are not yet a mandatory requirement in all countries. Among the countries that have made TCFD reporting mandatory are UK (2022), Japan (2022), New Zealand (2023) and Switzerland (2024).

[Source: TCFD 2022 Status Report]

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is another example of a sustainability-linked macro risk, as is biodiversity loss, a theme taken up by the Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures or TNFD which was launched in July 2020 as a parallel to TCFD. These macro risks will have varying impacts on a business, i.e. will have varying degrees of materiality. However there is also an argument to be said that the overlap between the triple threats of AMR, biodiversity loss and climate change means they are a systemic risk that all asset owners and managers need to be on top of. This is something we cover in our primer on AMR but it is increasingly reaching the mainstream (a very good thing!). Here is an example of where it is well covered by Aviva Investors, the University of Exeter Medical School and the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy.

The danger of "just give me the data"

Even as the world has become increasingly aware of the significance of environmental and social factors and the governance required to manage those risks, ESG investing emerged with, in effect, that same EV approach, relying on data and scoring to assess how exposed a company is to ESG risks.

Let's take a look at a few of the major ESG metrics providers' messaging:

"MSCI ESG Ratings aim to measure a company’s management of financially relevant ESG risks and opportunities... identify industry leaders and laggards according to their exposure to ESG risks and how well they manage those risks relative to peers."

Sustainalytics (owned by Morningstar) refer to their ESG risk ratings "measure the degree to which ESG issues are putting the EV at risk."

Dow Jones sustainability data are "a transparent, timely set of ESG factors that can serve as indicators of potential material impact to a company’s bottom line."

Data is extremely useful in the investment decision-making process. It is one of the inputs into the process that also includes qualitative assessment and consideration of relevant factors, for example the fund or business strategy, existing investments or positions etc.

In one of my roles at Morgan Stanley, I managed a team engaging both quantitative investors and fundamental investors looking to utilise data and quantitative techniques. At that time the availability of 'alternative data' or non-traditional financial data that you wouldn't normally find in the annual report had exploded and there was a rush to acquire 'innovative' data sets - 'just get me the data' was the rallying cry amongst newly interested discretionary investors. The output from their new data-driven models seemed to take on a disproportionate emphasis on the decision-making process, almost becoming the process. That was my observation at least.

The problem with a purely data-led approach (even if that wasn't the original intention) in sustainability investing which focuses on an aggregate score, is that the motivation for an organisation being rated is to strive for a better score by scoring highly on every metric and try to address everything.

The danger of taking that broad brush approach to sustainability is that it can lead to accidental or inadvertent greenwashing. We shall look at greenwashing more closely as it pertains to the investment process in an upcoming blog.

In summary, there are a number of sustainability themes and environmental, social and governance issues that are important and can influence business and investment decisions. They are material. Historically they have been looked at from one direction: the impact 'of' the risk, really a risk management exercise from the business's perspective. This considers the business as an isolated entity that generates returns in the face of risks and other dynamics impacting it.

But businesses are not isolated. What if we started considering them as part of a broader ecosystem?

Looking both ways: double materiality

The European Commission published its guidelines on non-financial reporting shortly after the TCFD report in June 2017 going one step further in recommending that when assessing the materiality of non-financial information a new element should be taken into account - "the impact of [the company's] activities." The concept of 'double materiality' was brought into mainstream thinking. Companies now needed to consider not only the impact of climate on their operations, the 'of', but also the impact of their operations on the climate, the 'on'.

The latest beta framework for TNFD ('v0.3') incroporates the double materiality approach too incorporating "dependencies and impacts on nature alongside risks and opportunities to the organisation."

The TNFD framework is expected to be finalised by September 2023 and will potentially align with the Global Biodiversity Framework which is produced by the Convention on Biological Diversity ('CBD') which hosts its own 'Conference of the Parties' in parallel to the longer running climate COPs.

Both TCFD and TNFD provide the high level guidance for standard setting bodies to use to inform their development. So, for example, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) will follow that guidance in developing the IFRS Sustainability Reporting Standards, which will provide detailed and specific requirements for, in this case, corporates when it comes to financial and non-financial disclosure. In other words, Standards are what make frameworks actionable.

Standards = "specific, detailed, and replicable requirements for what should be reported for each topic, including metrics."

[Source: SASB/IFRS Foundation]

For asset managers and investors, frameworks such as Regulation 2019/2088 of the European Parliament and the Council passed in November 2019, better known as the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), are also applying a double materiality principle through its Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS). These will most likely apply from 1 January 2023 for "manufacturers of financial products and financial advisers towards end-investors" or in other words asset managers, institutional investors, insurance companies and pension funds among others.

The SFDR provides some guidance on classification of funds according to their approach to sustainability, however, I shall focus on two of the high level disclosure principles (it is just more relevant to the discussion topic of this article!)

Those are:

- Article 3: Sustainability risk = how are you integrating sustainability risks into your investment decision-making process, investment advice or insurance advice?

- Article 4: Principal Adverse Impacts = how are your investment decisions impacting sustainability factors? or indeed why you do not consider them!

Or in other words...

There are many frameworks and this can, at least currently, make it difficult to know what exactly should be disclosed, but that's a topic for another blog.

TCFD = 'Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures'

TNFD = 'Task Force on Nature-related Financial Disclosures'

UNPRI = 'United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment' - investment implications of ESG factors.

GRI = 'Global Reporting Initiative' - impacts on environment, society and economy.

CDP = formerly the 'Carbon Disclosure Project' - focused on climate change, forestry and water security.

GRESB = framwork / scoring for the ESG performance of real estate assets.

The shift from an Enterprise Value (EV) approach (what are the risks 'of' X to the business? Can the business manage these material risks and opportunities?) to the double materiality approach considers the business as part of a broader ecosystem that includes people and planet. Rather than 'EV' we should be thinking about the bigger picture, the whole pie.

Focus on what is important and relevant - practical examples

Hand-in-hand with materiality is the concept of relevance. For something to be material it has to matter to the business and its stakeholders. It has to be relevant.

Relevance could be a tool to help guard against inadvertent greenwashing. Rather than attempt to address or demonstrate that an organisation is addressing all of the UN SDGs, isn't it better to focus on the few that can best be addressed by the business and that are relevant to all of its stakeholders?

Let's look at a couple of examples of where organisations have aligned their focus on the core of their business and what is material to their stakeholders.

Case study #1: Biogen - Healthy Climate, Healthy Lives

Biogen is a biotechnology company specialising in finding treatments and cures for neurological conditions, so those involving the brain, spinal cord and other peripheral nerves. They have a number of medicines addressing Alzheimer's Disease, Multiple Sclerosis, and Spinal Muscular Atrophy.

Their 'Healthy Climate, Healthy Lives' initiative hits the intersection of the broad theme of climate change and their core business of brain health. The negative impacts of climate change have an impact on brain health. It is a US$250 million programme across three pillars to move operations to be 100 percent fossil fuel free, engage employees and foster global collaboration on these efforts.

Whilst their end goals are for 2040, they also have interim or milestone targets too. For example, they seek to transition 100% of the vehicle fleet to electric by 2040, but with an interim target of 2,000+ vehicles switched to electric by 2025.

They have also looked through their supply chain with a goal to commit 80 percent of the suppliers by spend to set science-based targets on climate by 2025, commit 50 percent of suppliers to source 100% of their electricity from renewables by 2030 with 90% by 2040.

Finally, they have sought to build the initiative into the DNA of the organisation with goals to assist and engage their employees too. For example, providing incentives and the capability for employees to go fossil fuel free in their own homes.

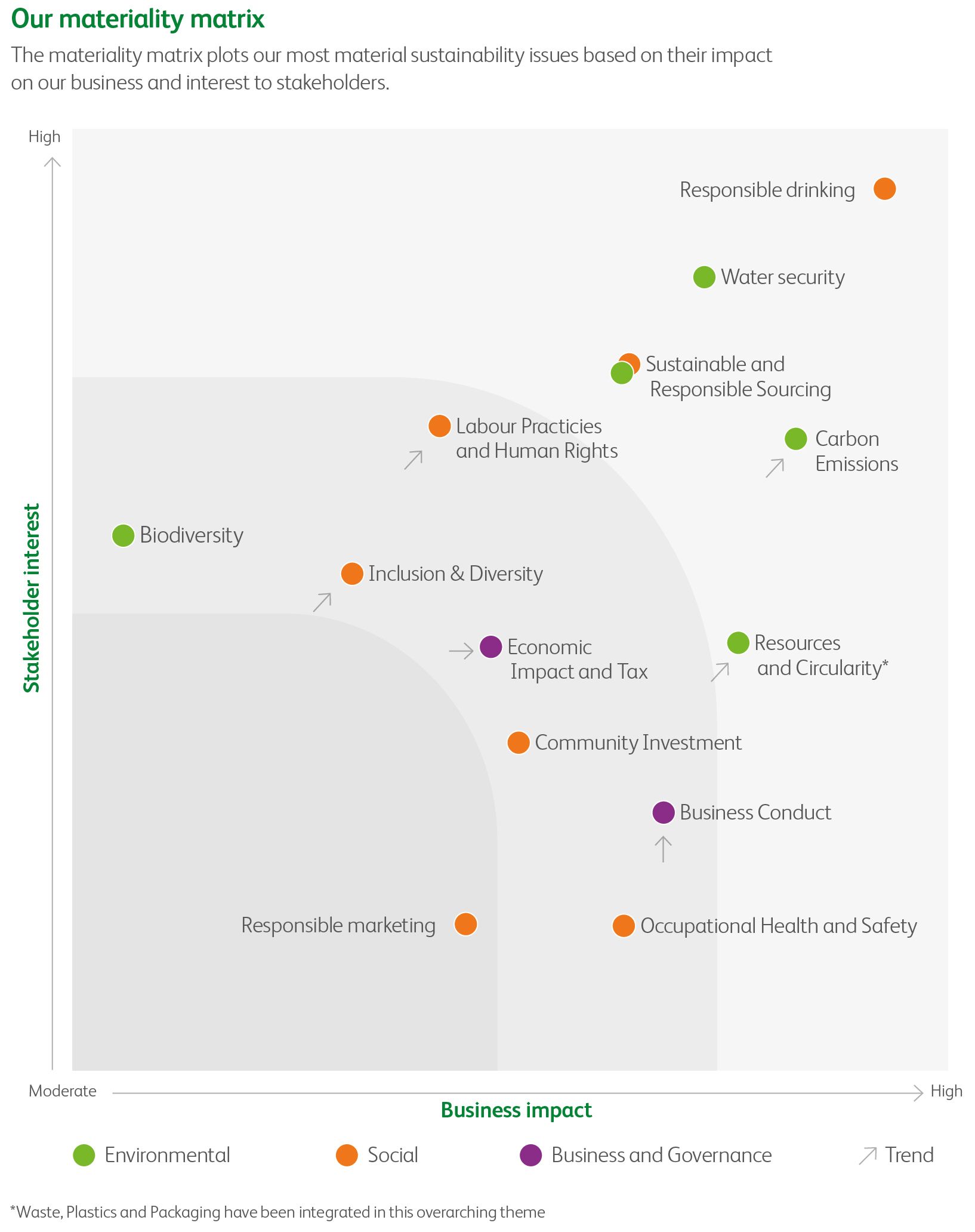

Case study #2: Heineken - Brew a Better World

Heineken is an international brewing company with more than 300 beer and cider brands distributed globally.

One of Heineken's five strategic pillars is to step up in sustainability and responsibility. Their 'Brew a Better World' programme is designed to deliver on that and focuses on those UN SDGs that are relevant to Heineken's business under the areas of Environmental, Social and Responsible. Some are quite recognisable, such as reaching net-zero carbon emissions, maximise circularity and embracing inclusion and diversity. Some are more industry specific such as a focus on low or no alcohol choices and campaigns supporting moderation.

Within each of these focus areas Heineken have made specific, time-associated commitments that guide their business decisions and actions. This ranges from overarching societal goals like decreased plastics use to decisions that have resulted in an entirely new business stream - their lo-and-no alcohol portfolio has grown leaps and bounds over the past several years, spurned in part by the company's goal to support 'moderation' in alcohol consumption and as a remarkable spinoff from the lockdowns of recent years, when consumers became increasingly aware of at-home alcohol consumption, for example.

This move is interesting as very much within the "Grow the Pie" mentality as at first glance it seems as though they are creating a competing product to their classic alcoholic beverages. However, they are also growing and developing a new market. In 2021, the Heineken 0.0 brand sales were 6.7 percent of consolidated beer volumes or 15.4 million hectolitres. That is the same as 616 Olympic-sized swimming pools and almost half of the other Heineken brand beer sales by volume. Heineken 0.0 is now the largest non-alcoholic beer brand in the world and available in more than 100 markets.

Their materiality matrix is a good example of consideration for where a business can make the most impact in a way that is relevant to both their business and their stakeholders.

Conclusion

Historically there has been a one-way view on materiality, what are the risks 'of' X to the business? Can the business manage these material risks and opportunities? An Enterprise-centric and EV approach.

ESG investing emerged with, in effect, that same EV approach, relying on data and scoring to assess how exposed a company is to ESG risks.

However, as a broader group of stakeholder interests have come to the fore including employees, customers and the community at large there has been a shift in thinking from not just considering the impacts 'of' the environment, social and governance aspects and how they impact a business but also the impact of the business 'on' the environment and society as a whole. In other words, considering the business as part of a broader ecosystem.

With that in mind, if businesses understand how they fit into that ecosystem and the materiality and relevance of their actual and potential impact, they can be the most effective and align their values with creating value.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.