Defining what a sustainability linked bond is

Standards matter - vagueness in the definition of what makes a sustainability linked bond makes it tough for investors to be sure that they "do what it says on the tin".

Summary: Standards matter - vagueness in the definition of what makes a sustainability linked bond (SLB) makes it tough for investors to be sure that they "do what it says on the tin".

Why this is important: SLBs are relatively new but have been subject to a number of criticisms from their lack of ambition from issuers, the low level of punishment and the ability to wriggle out of paying the extra coupon.

The big theme: Debt markets can play a massively important role in funding and encouraging companies that contribute to sustainability. In many ways it's a more important market than equity, as the debt markets are where most companies raise new capital. New global "green" bond (GSS+) issuance last year (2021) was $1.1 trillion, making up c.5% of all bond debt priced. However, investors face a challenge in assessing some GGS+ bonds because of their often simplistic or opaque key performance indicators.

The details

Summary of a story from The Bureau of Investigative Journalism:

HSBC has committed to contribute up to $1 trillion in sustainable financing and investment by 2030. An analysis of the bonds HSBC counts towards its sustainable finance target found at least $2.4bn worth of deals for companies that are worsening the climate crisis. Central to the issue is a relatively new financial product known as a sustainability-linked bond (SLB). SLBs are an ostensibly green type of debt, designed for companies to raise money to fund their transition to more sustainable activities.

Companies that raise funds through SLBs do not face tight restrictions on how that money is used; instead, they agree to certain targets related to sustainability. But these targets are often remarkably weak and the penalties for failing to meet them can be paltry – leaving SLBs as a way for companies to give the appearance of environmental concern while continuing to worsen the climate crisis.

Let's take a look at why this is important...

Why this is important

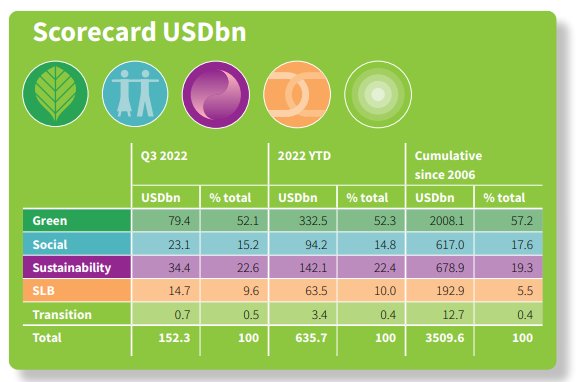

First, some perspective. According to the well-regarded Sustainable Debt Market Summary (3Q 2022) from the Climate Bonds Initiative, Sustainability Linked Bond (SLB) issuance over the first 3 quarters of 2022 was $14.7bn. This made-up just under 10% total GSS+ bond issuance for the period. To be clear on definitions: GSS+ is the total of Green, Social, Sustainability (together GSS) plus SLB & Transition bonds.

SLBs are a fairly new bond instrument, with the first bond issued by ENEL in 2019. The key difference between SLB's and other GSS bonds is that the proceeds are not linked to specific projects, but instead the money raised can be used for general corporate purposes. The structure is straightforward: the bond has a coupon (interest rate) linked to a Sustainability Performance Target (SPT). The issuer pays less interest on the debt if it hits those targets but more if it misses them. Taking an example from the BIJ report quoted, UltraTech (the issuer) had a target for the company to cut emissions by 22% per tonne of cement produced by March 2030.

SLBs are subject to a number of criticisms. The first is one of a lack of ambition, with some issuers looking set to easily achieve their SPTs. One example often quoted is the ENEL bond above, which only required them to increase installed renewable energy from 45.9% to 55% of total capacity.

The second is the low level of punishment (via a higher coupon) if targets are not met. In most cases this is only a 25bps step up, which for many borrowers is a small price to pay. This is especially the case if the assessment date for testing achievement of the SPT is only a short period before the bond matures (again, using the Ultratech example from the BIJ report, the test date is only 6 months before the maturity date).

The third is the ability to wriggle out of paying the extra coupon. A recent case of this was Sembcorp and its Indian coal assets. They agreed to sell them to a private consortium but as part of the sale they agreed to continue to finance the coal assets for the next 15 years. Just enough to get them off their books for the SPT test, but it raises questions of "form over substance".

As Ulf Erlandsson, founder and chief executive of Stockholm-based non-profit think tank Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute (AFII) said recently - it would not take a great deal to tighten up the SLB market. "If you correctly structure the bond, and you engage with the issuers, you can drive issues to align with environmental and sustainability policy.” That will, however, require investors to make their needs clear and to dig into the bond documentation, rather than investing in SLBs purely as a box-ticking exercise.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.