Feed the world - Changes to feed and Total Resource Productivity

Agricultural reform including waste and byproduct management could ensure the global population has sufficient nutrients.

Summary: We look at two approaches to reform in the agricultural sector. One involves changing an aspect of the agricultural system - replacing livestock and aquaculture feed that could be used for human consumption with food system by-products and residues - whilst the other proposes a wholesale reform.

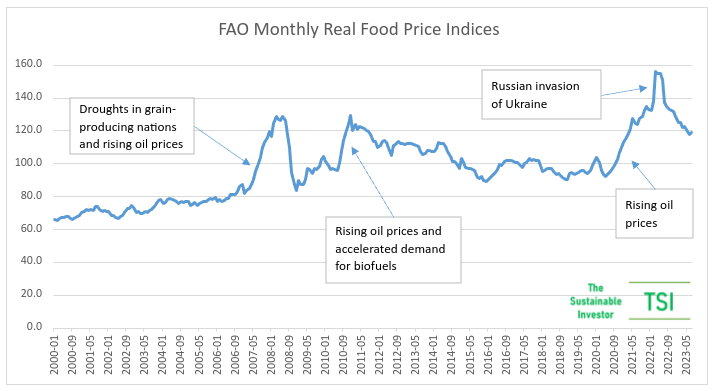

Why this is important: Many larger investible companies rely on our agricultural supply chains (think food producers and supermarkets for instance), so it’s a big long-term issue all investors should be considering. Recent food supply disruption and price inflation will bring it more to the fore.

The big theme: Agriculture (and its sibling, aquaculture) sit at the intersection of a number of UN Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs). As one reads through the list of goals they are either directly relevant (for example goal 2: zero hunger or goal 3: good health and well-being) or have a causal relationship (for example, education improving with better nutrition and less pollution). Reforming agriculture is a big deal, in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, environmental impact, food security and rural society. But it’s going to require massive social and economic change and disruption, to production methods, to supply chains and to employment. It’s not clear that the political will to change fast enough really exists, which could mean faster and more dramatic change needs to come in the future.

The details

Change how animals are fed: feed an extra billion people

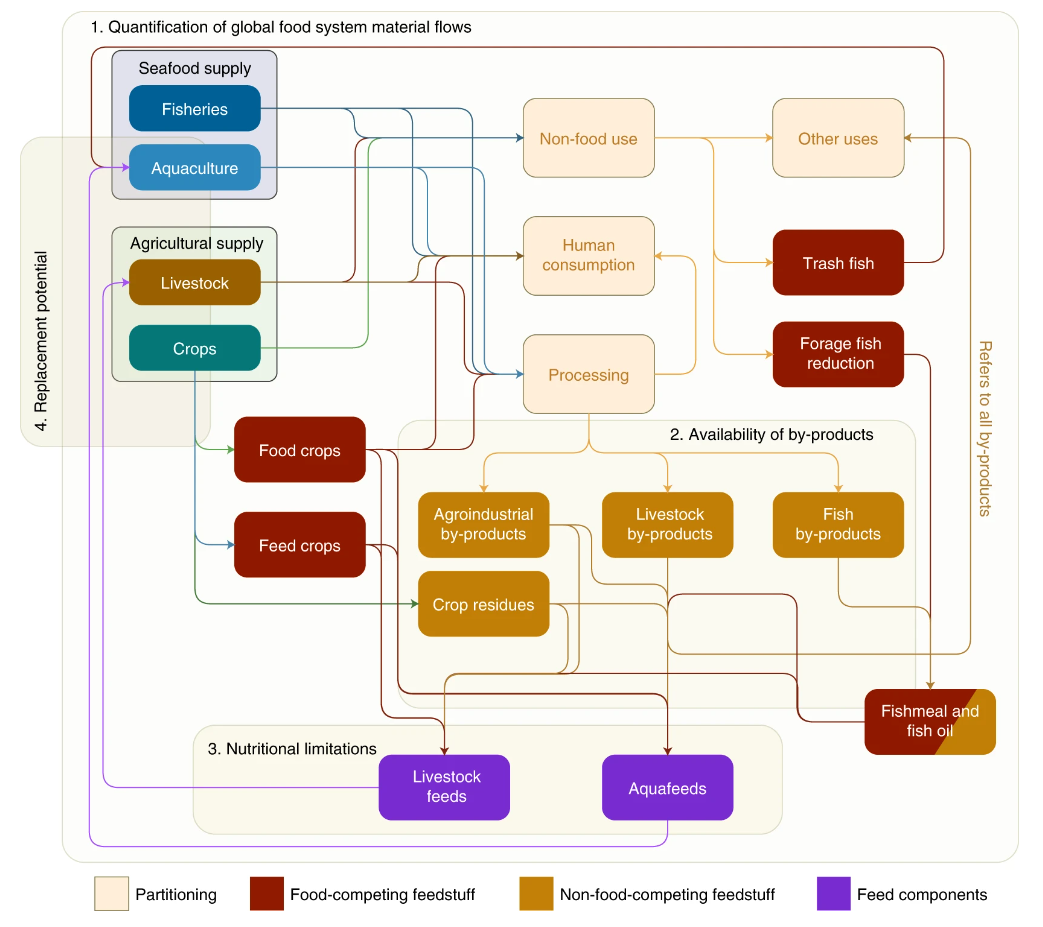

Researchers from Aalto University in Finland, led by associate professor Matti Kummu examined how food and feed flows through the global food production system. They concluded that replacing livestock and aquaculture feed that could be used for human consumption with food system by-products and residues could free up enough food to feed an additional one billion people. The changes proposed could redirect between 10-26% of total cereal production and approximately 11% of current seafood supply to human use. This would represent as much as 15% of current food supply protein content and up to 13% of caloric content.

Why this is important

There is less interest from investors in the whole agriculture and natural capital space than its importance deserves. Yes, it’s a big topic in the private space, but not in public equities. Some of this is due to an absence of quoted investments with an obvious exposure to the theme, and many of the companies that do exist are smaller, local and less liquid. But, if you think about it a bit more deeply, many larger investible companies rely on our agricultural supply chains (think food producers and supermarkets for instance), so it’s a big long-term issue all investors should be considering. Maybe recent food supply disruption and price inflation will bring it more to the fore.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) currently estimates that almost 690 million people (just under 9 percent of the global population) are hungry. UN SDG 2: Zero hunger, aims to eliminate hunger and ensure access by all people to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round by 2030. The UN believes that under current assumptions that goal will not be reached, with more than 840 million people still suffering from hunger by 2030.

Currently almost 40% of arable land and more than 30% of cereal crop production is used for animal feeds, whilst 23% of all captured fish are used for fish and livestock feeds and other non-food uses.

According to data from the FAO Global Livestock Environmental Assessment Model (GLEAM), 86% of the 6 billion tonnes of dry feed matter consumed by livestock annually is made of resources not edible by humans, with the bulk made up of grass and leaves (almost half). Crop residues and by-products already make up a proportion of livestock feed (almost one-quarter).

However, whilst accurate, the “86 percent” figure could be misleading. A 2017 study found that “producing 1 kg of boneless meat requires an average of 2.8 kg human-edible feed in ruminant systems and 3.2 kg in monogastric systems. While livestock is estimated to use 2.5 billion ha of land, modest improvements in feed use efficiency can reduce further expansion.”

Climate change continues to be the major macro factor impacting the availability of sufficient food for the global population. Indeed, if GHG emissions were allowed to grow unabated, then by the end of the century more than 33% of current global food production would be “out of safe climatic space.” Food systems themselves are responsible for 37% of GHG emissions.

An earlier study from Kummu’s team found that “...reducing food loss and waste by half would increase the food supply by about 12%. Combined with using by-products as feed, that would be about one-quarter more food.”

What other issues does this raise?

Historically, investment in agriculture has been focused on increasing yields - from research into pesticides and fertilisers through to agtech designed to irrigate, cultivate and process more efficiently. There have also been innovations looking at reducing feed requirements, it’s just these generally get less attention.

Insects, as well as being a potential alternative source of protein for humans (being commonly consumed in Asia, Africa and South America already) could also be substitutes for fishing and pet foods.

Mycoprotein made from fermenting fungus is another partial substitute to reduce overall livestock requirement.

Aquaculture has bred (no pun intended) a number of feed initiatives from fish food substitutes including those made from microalgae to creating symbiotic relationships such as cultivating sea cucumbers alongside marine fish farms feeding on the waste from those farms. Finally, lab grown or cell-cultivated protein offers another solution with companies such as BlueNalu focusing their cultivation on overfished and difficult to farm species such as Bluefin Tuna.

A complete overhaul: Shift focus from just increasing yield, to improving the total system efficiency.

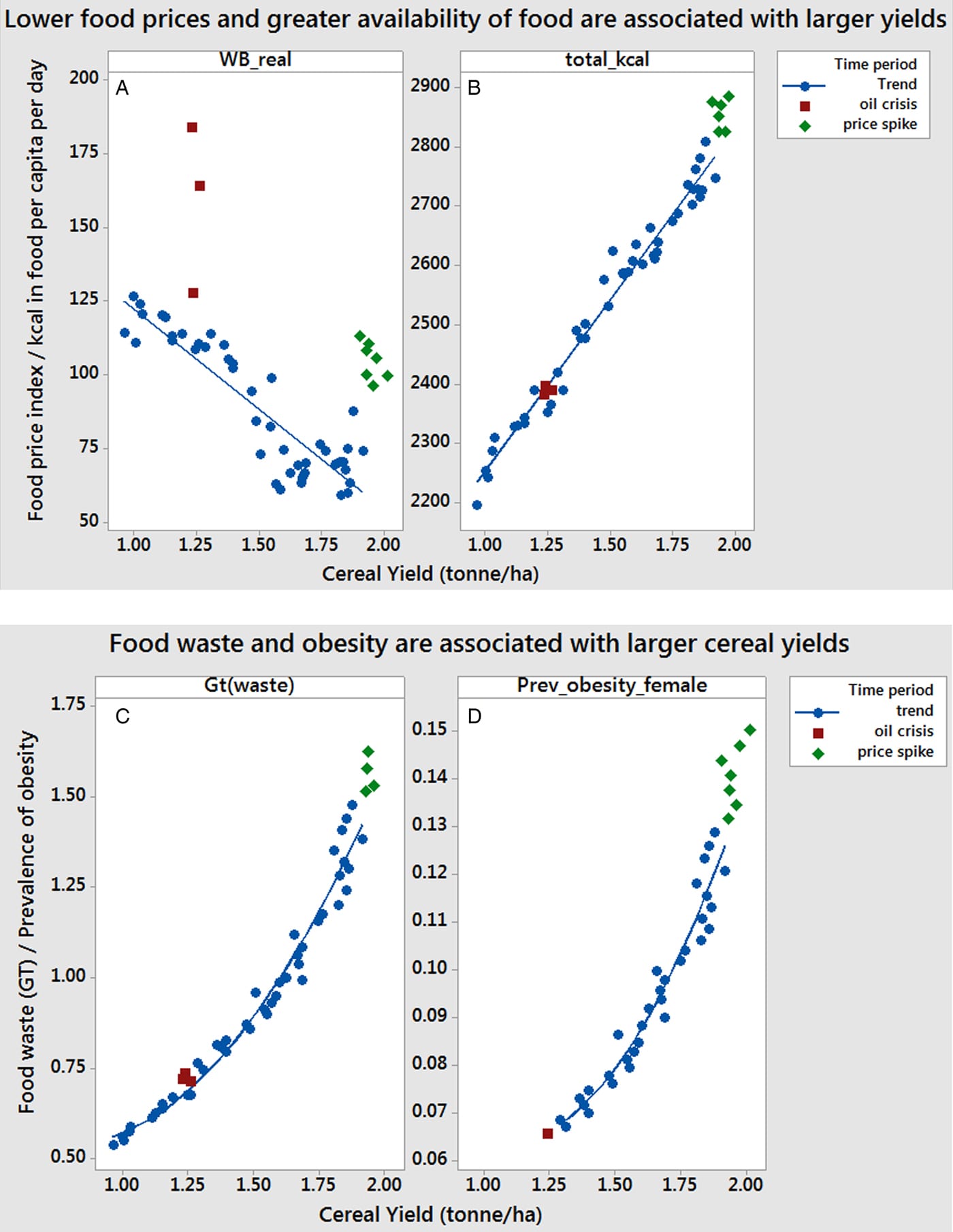

Could it be that a focus on productivity promotes system inefficiency? This interesting hypothesis is put forward by Tim Benton and Rob Bailey from the Energy, Environment and Resources Department at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, Chatham House. The key is where that focus is. They propose shifting the current policy focus for food from yields per unit input or ‘Total Farm Productivity’ to the number of people that can be fed healthily and sustainable per unit input or ‘‘Total Resource Productivity’. This would, in their view, increase the efficiency of the overall food system.

The focus on ‘yields per unit input’ has led to a massive growth in agricultural produce supply and subsequent declines in price. However, the availability of increasingly cheaper calories has led to a vicious circle of increasing demand for cheaper production, driving damage to the environment, increasing waste, and higher levels of obesity (now exceeding the prevalence of underweight).

Measured as the amount of food grown that is eaten by humans, the current inefficiency in the global food system is a result of the drive for efficiency at the farm level - the “paradox of productivity.” Production has become specialised on a small number of highly productive crops crowding out traditionally grown varieties and creating a dependency risk on certain areas of the world (e.g. the so called ‘breadbasket’ areas). More than 50% of the world’s crop calories as of 2014 came from just 3 things: wheat, rice and maize. More than three-quarters of all crop calories came from those three plus sugar, barley, soy, palm and potato.

Why this is important

Although this paper was published in April 2019 (how did we miss it then?) it is still very much relevant today - hence why we are repeating it. As mentioned previously, most agricultural innovation historically has been focused on improving yields. However, there have also been a number of rather obvious yield improving measures that have been ignored.

These include wasted fruit and vegetables at the point of harvesting for not being the right shape, through to surplus fresh food thrown away at the point of sale or in our homes. In the UK for example it is estimated that 3 million tonnes of good, edible surplus food is thrown away each year. UN Sustainable Development Goal 12.3 aims to halve food waste at the retail and consumer level and to reduce food loss across supply chains.

There is also a climate change imperative. Food waste itself generates a large amount of GHG emissions. It is estimated that if food waste were a country, it would be the third largest emitting country in the world (between 8 percent and 10 percent of global GHG emissions).

The authors put forward a number of individual policy measures to achieve their aim including cross-disciplinary, cross-sectoral framings of the issues, incorporating social and environmental costs into food prices (balancing the implied regressiveness with improving intergenerational equity), greater contribution from governments on the debate, rebalancing of subsidies to agriculture, reducing waste throughout the chain, new technologies and new norms (such as veganism, vegetarianism and flexitarianism).

What other issues does this raise?

The yield improvement focus has led to a reduction in the variety of crops providing calories with a focus on a small number of crops. The creation of hardier strains of wheat through cross-breeding, for example, has produced strains that contain novel proteins that are hard for many to digest. A return to a broader set of crops can not only potentially help reduce inflammation but also there is an important social aspect in encouraging the growth of local and indigenous communities, increasing subsistence and rejuvenating local areas. From a risk management point of view, it can also potentially stabilise food prices - the Ukraine conflict drove the FAO Food Price Index up 12.6% in March month on month.

From an investment perspective, there are a number of interesting areas for development. The removal of expiry dates and the marketing of so-called “wonky fruit and vegetables” reduces waste at supermarkets and can have a financial benefit too. When Morrisons brought in their wonky produce line, it boosted its own-label sales by 18%. Vertical farming could be a low footprint way of producing all manner of produce and it can even reduce stocking times and transport costs and emissions by locating within retail stores. Taking the previous point further, the relocation and dispersion of food production to be closer to the point of consumption will also have implications for associated infrastructure such as cold chain logistics (freezing food at point of harvest is a way of reducing waste too), employment migration and seasonal consumption.

Conclusion

As a major source of GHG emissions, water usage and a vector for antimicrobial resistance propagation (see our AMR Primer), the agricultural industry is in need of reform. This will not be easy, but there are steps that can be taken to ensure that we get the nutrition we need in harmony with both planet and population. We shall be exploring in later blogs.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.